This piece kicks off our ACE & Creativity Series for the 2022-23 academic year.

I was introduced to Giovanni Strazza’s The Veiled Virgin by a (then) stranger, Alice, in a Liverpool café one morning in 2017, before we and our shared friends walked to the Walker Gallery and enjoyed an exhibition featuring the pre-Raphaelites. Alice showed me a picture of the bust on her phone and I was beguiled by its grace and the skill that was needed to hew it out of stone. The link between the bust and the exhibition we were about to see didn’t appear notable at the time, but this quickly changed. Upon entering the gallery and reading about Dante Gabriele Rosseti and his colleagues’ opposition to the popularity of Renaissance works and the like, it struck me that at the time the artistic movement came to fame in the mid-1800s, in Rome, Giovanni Strazza was actively continuing those traditions, creating The Veiled Virgin, no doubt drawing on Renaissance and Rococo sculptures such as Michelangelo’s Pietà and Corradini's Modesty. How would the pre-Raphaelites have viewed Strazza’s bust? I’m sure we can guess.

Nevertheless, despite such popular and critical voices, in many minds, Classical traditions of art and representation continued to flourish, and are still appreciated and reimagined. For Strazza, Graeco-Roman sculpture symbolised Risorgimento, the unifying of his country by honouring its religious and artistic heritage. All of this speaks to the continuation of an ancient conversation about the artistic depiction of the human form and how it can be read. I returned home that day and opened my drawing pad, found The Veiled Virgin online, and started planning my own critical appreciation in graphite. I now sit in the Antiquities study room in the Ashmolean Museum, writing this commentary, with a pre-Raphaelites exhibition merely a dozen feet beyond the wall besides me; it feels like a full circle moment, yet the conversation continues.

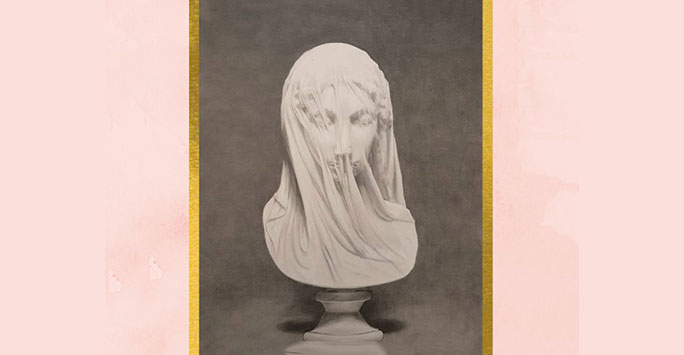

I approached the sketch with an aim: to champion the marble of the bust. Marble has a peerless ability to capture the grace of motion, action, and subtlety, all of which has made it the material of choice for sculptors since Antiquity. For The Veiled Virgin, marble was the only choice. Marble’s slight translucency, allowing light to penetrate a few millimetres beneath the surface, scatters a defuse outer glow throughout a sculpture. It is this feature of marble that makes the stand-out feature of Strazza’s sculpture, the veil, a success. Paradoxically, the stone veil does not hide the Virgin below, but reveals her in no more or less detail than is absolutely required to perceive her quiet grace. The stone was worked to look as soft and fine as chiffon, preserving the gentle skin below, but still reads as marble, and so becomes a marvel of technical aesthetics. If my sketch was to be successful, I had to capture the magic of the marble, not simply a veiled woman.

My sketch is drawn using graphite pencils, ranging from 4A to 4B (hard to soft graphite). This limited palette of pencils is not typical for modern sketches, where contrast is king, and few artists leave a work untouched by 6B or softer (darker) graphite. However, surely if a monotone slab of marble and light could create the infinite subtlety that the bust achieves, then I felt that must be preserved in my sketch. Smooth gradients and transitions are achieved by layering graphite on the paper surface with a light touch. This method only works if the pencils remain pin-sharp, as dull pencils polish the graphite as they place it on the surface of the paper. The skill to this is not to let even the weight of the pencil to bear down on the paper’s surface. By lifting the pencil as I draw, the point of the pencil glides effortlessly across the tooth of the paper, hard lines fade and are united to create a uniform consistency. Burnishing (pressing heavily) using a graphite pencil creates a shiny and metallic surface on the paper and moves the depiction away from marble and towards metals or polished stone. A piece of scrap paper beneath my palm stops my skin from blending marks, the oil mixes with the graphite and ruins the intention of the marks. Again, it is important not to lean on this and add unnecessary weight, or this will inadvertently burnish the graphite. I layered a variety of pencils, using cross-hatching (overlapping marks in different directions), to achieve the desired matte result. This work was my first foray into using brushes with pencils to blend the graphite, and I instantly became a convert, leaving the comparatively archaic blending stumps behind for good. Brushes smoothly blend graphite and do not scratch the paper if a sharp sherd of graphite has chipped off the pencil during shading, whereas typical shading techniques can pick this up and embed it into the paper or create distracting spots or blemishes. In places, I sketched with the brush, by loading it with graphite that I scribbled on a spare scrap of paper. This technique provides unrivalled control and the most delicate shading. The paper is entirely covered in graphite. ‘White’ areas are achieved, not by leaving the paper bare, but contrasting lighter shades with darker regions nearby. The human eye perceives contrast well and reads the result as white, even where it is not.

Through the marble veil, the positioning of the nose and mouth hint at the down turned face. The eyelids, closed, echo the silhouette of wide-open eyes, allowing her to stare back at observers and invite a connection. The shadows structure the face with squared shapes, but the soft shadows stop the face appearing geometric. Likewise, care was taken when adding the folds in the veil not to allow them to carve into the facial features. The veil kisses the cheeks, but hugs the chin, flattens the hair, and sharpens the nose. It pools over the neck and carefully fades before reaching the perimeter of the neckline. These aspects balance the work and remind us that it is contained in stone, and, despite appearances, is solid.

I applied contrasting approaches to the base and the fading background. I roughened the shadows upon the base to reinforce the notion of carved, but not polished, stone. This was a liberty that diverted from the reality of the bust, but endeavours to contrast with the silken texture of the head. The composition seeks to elevate the subject and allow the base to recede into the background where it can meet the darkening background. I was tempted to use a graphite powder, brushed onto the surface and blended, to achieve a perfectly smooth background behind the bust. The benefit of this approach would be to ensure that the background could not steal any attention away from the main subject. I chose instead to apply the far less consistent method of cross-hatching increasingly darker shades of pencil up to 4B. The result is a finely chaotic network of interlocking pencil strokes that juxtapose with the tranquil subject, pure and centred.

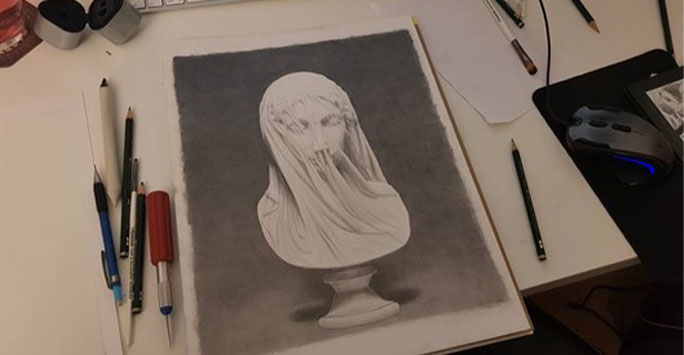

I did not track the time taken to create the sketch. It took months and many dozens of hours. I don’t draw quickly or consistently, only when I feel in the mood to. I find drawing and painting therapeutic and relaxing. I put on a podcast or listen to music, anything other than silence works for me. I suppose I am a technical artist and enjoy the processes and methods, refining and reworking them, until they achieve the result I am looking for. My rendition of The Veiled Virgin is one of my favourite pieces; it is subtle and appears simplistic, despite the great effort which went into it. I’ve included a picture of the work in situ on my old desk, just as the final touches were applied and the paper was cut to size for the frame. I’m curious what a pre-Raphaelite would have thought of it, and am heartened that Classical art, and the movements it inspired, still stir the expression of the human experience in 2022.