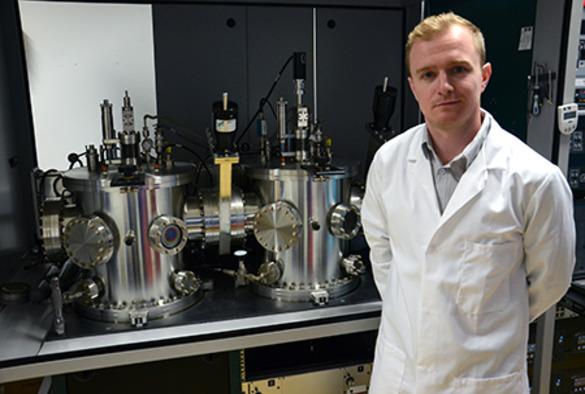

Jon Major

'Whenever I'm teaching, I always like to try and have a degree of enjoyment and fun, it should be interesting. Physics has you are learning amazing things, so why should you not be enjoying yourself while you learn it?'

Can you introduce yourself, your role in the university and tell us a bit about your background?

I am Jon Major, I am a reader in the Physics Department, so my role is to teach within the department, do various admin things like running our course rep meetings. I also have a research group, and we are conducting research into new forms of solar energy. We work on something called thin film solar cells which is going to be hopefully a cheaper more efficient way of generating power. I am originally from West Cumbria in the absolute middle of nowhere! I went and did my undergraduate degree in physics with medical applications at Newcastle and then did my PhD at Durham stayed on there for a postdoc and ended up here.

Why did you choose to work in the University of Liverpool?

I did my PhD and postdoctoral research with Ken Durose, he teaches in the fourth year at Liverpool. Ken was my PhD supervisor and then I stayed on with him to do a postdoc. While I was working in Ken’s group at Durham, he got an offer to come and work at the University. One of his conditions to move down here was a job for Jon. So, I found out by accident because Ken had written it on the back of a bit of paper and I saw ‘Job for Jon’ scribbled down. That was in 2011, and we came down together at the start of the Stephenson Institute. Over time I gradually got more independent and started my own research group and I’m still here because Liverpool because it’s a really good university and everyone is really nice.

What does a typical workday involve for you?

Typical workdays vary a lot between the times of year. This time of year is lovely because I get to potter around, help out my PhD students in the lab, do some research and maybe go into the lab myself and make some solar cells. When term rolls around it gets that busy that I tend to be running around from various teaching things, various admin things, there’s always grant applications and papers to be written as well. My days are split between furiously trying to write things, trying to get teaching prepared and keeping my research going in the background. One of the challenges of being an academic is you have about three different jobs and none of them care about the deadlines for any of the other jobs! I had a point last year when I had a European grant, I was writing with seven other partners that had the same deadline as the exam papers for the undergraduate teaching and I had to get ready for the term starting to teach lectures. So, my days can be anywhere from really calm to very frantic.

What research are you currently undertaking?

My group is mostly focused on a material called antimony selenide for solar cells. This is a new material that has better properties than the existing solar cell materials but it's a very new, so it requires a lot of development work. My group are making small test scale solar cells, and we try to develop new processes or new methods, then we test the power output from the cells. If we find something that makes the cells better then we work out what's going on within the materials, what's changed and why that led to improvements. The idea is we could make these new technologies that could be cheaper than the existing ones or they could find different applications, so we're interested in things like indoor solar cells for sensors.

What is your favourite part of this research?

I like the self-contained nature of it. I think with the with the big scale research projects everyone's working on the same thing, so you've got the big project and everyone's a cog in the machine of that giant project. We’re a bit more sort of artisan in that we know the area want to work in and we're able to work on whatever is catching our interest at time, so it's that adaptability in the discovery led nature of it that I like. Most of our research projects will stem from me and one of the PhD students talking and then we'll just say, ‘well let's do that then!’ So, then we try it and see what happens, so I like the discover part of it. Going to conferences is always nice as well.

Why did you choose to pursue a career in physics?

I would say the career in physics is almost by accident. I was a PhD student, then I was postdoc and then suddenly, I was an academic and at no point has it felt like a particularly conscious choice. I've just sort of drifted into it gradually because I don't think I ever thought I could have an actual career in physics. I did physics at university because I had a phenomenal teacher at school called Mr. Tomlinson. He always used to teach physics with a degree of fun, every example he would teach usually involve either his campervan or his cat Olly. So, it would be like “Mr Tomlinson's camper van is moving at 3/4 of the speed of light if Olly falls out the back, what is his relativistic speed?” He made it so interesting and fun that it just kind of stuck with me compared to anything else. I was always good at maths, but I found it slightly dull, so I just went into the physics which was more interesting and then I've never quite got out of it.

How have your past experiences shaped your approach to your teaching and research?

The Mr. Tomlinson approach sort of stuck with me because I tend to do stupid stuff whenever I'm teaching, I like to have fun with it. I always think learning physics should be fun, and I had a lot of lectures at university that would come in and write on the blackboard for an hour while you scribble it down as fast as you can. Then you would see if you can figure out what you can get from it. So, I always like to try and have a degree of enjoyment and fun, it should be interesting, and it should be exciting. That's one of the main things, physics has you are learning all these cool things, so why should you not be enjoying yourself while you learn it.

Did you face any challenges along the way and how did you overcome them?

I guess a lot of a lot of academics are like this, but Impostor Syndrome is a big one and a bit of a big northern chip on my shoulder to be honest. I almost drifted into being an academic and if you'd asked me when I was like a PhD student, I had no intention whatsoever of becoming an academic. I thought people like me didn't become academics as I don’t really fit my vision of what an academic should be. But then over time people kept saying “you could do this you know”, but even then, the thoughts of “I'm not the type” or “I'm not smart enough” creep up. Slowly, I just had to accept that maybe I could do it. Even now though I still have days where I expect someone to come into my office and say, ‘Right come on off you go, back to work in the chip shop where you’re supposed to be.’ So that's the biggest challenge, just the constant self-doubt and the Impostor Syndrome. I would say I am overcoming it to an extent on the bad days it's still there and I don't think that ever truly goes away.

How would you describe the environment at the University of Liverpool?

I think that the university in general has a has a great atmosphere and I think that's partly due to the city. I don't think I would want to live anywhere else, as soon as we moved here there's a feeling of it being part of the city and very much embedded in the culture of Liverpool. There’s that Scouse attitude based around openness and friendliness which tends to mean everyone's really lovely. I think the whole university has that sort of spirit of the city which is welcoming and lively where everyone's in it together. I think over time as I've been here you can also see the change in the Physics department, as it’s evolved even in the decade that I've been here. I think the department has a really good atmosphere now where it's a much more cohesive sort of community between the students, the teaching staff and the admin staff. Genuinely everyone's lovely which makes the department a very welcoming friendly place. I think as a department that's what we should really be. We're never going to be the world’s top research institution, but we could be the nicest one because of the city and the culture of the place. That's something we should aim for.

What advice would you give someone considering a career in physics?

I would say firstly do it, because one of the beauties about physics is that it can take you such a variety of places that other degrees can't necessarily do. Physics graduates are so employable in things like finance, business and other things like this because of the analytical skills that it teaches you. So, if you've got the capability to do a degree in physics absolutely do it because the world is your oyster once you've got that degree. But I would also say don't expect it to be easy, you've got to put the work in but it's worth it in the end. It also evolves the further you go. I hated undergraduate labs with a passion and the ones I had were nowhere near like here. Then I got to my fourth year, and by that time I thought I was no good at experiments and that I generally didn't enjoy doing them. Then I did my MPhys project which was in medical physics at a hospital in Newcastle. All of a sudden I had the opportunity to do this open-ended research project and I just remember thinking ‘This is physics. This is discovery.’ I was suddenly so into it that ultimately that enthusiasm led me here. I guess I would say that the hardest part of physics really is in the early stages of your degree but it’s there to underpin all the exciting stuff you'll do towards the end of your degree.

What are you hoping to achieve in the future?

I've done a lot of research and papers and things but what I'd actually like to do is be involved in a project that tangibly links to a real “thing”. It’s still ongoing but we're trying to get one funded with some European partners to take the solar cells we have made and link it to sensors to go down into mines to help with the efficiency of mining. I really want one of these projects that leads to a physical device where I get to say, ‘Right I made that!’ If we do start to get more towards that actual application of what we develop and we start to get something into the real world, that would be nice.

Is there anything else you'd like to share?

I know a lot of people will say they hate condensed matter physics; a lot of people say that when you speak to the third or fourth years. So I suppose I could extol the virtues of condensed matter a little bit which is that we're a bit different from the other groups. I have compared it before to us being like a herd of cats. The other research clusters are very focused with a clear goal, whereas in the condensed matter group we are broadly similar but we're all doing very different things. There’s me and Ken who're doing solar cells, you've got Tim and Vin who're doing analysis related to solar cell materials but then you've got people like Peter Weightman doing physics of cancer and Liam doing magnetic and spintronics. So, we're really a very diverse research area and I think that's one the strengths we've got in condensed matter. We get to cover this huge amount of area from electronics to renewable energy, to cancer and stuff like that, depending on what we find most interesting. So, condensed matter is this broad range of range of research from different areas that maybe other groups don't have.