December 2022 is finally here, and we are all waiting for the Christmas break to start the celebrations and welcome the new year with family and friends. On behalf of the ACE & Creativity team, I have the honour to write the last blog of this year, as an auspicious farewell to all our readers.

To me, an Italian living in Greece, Christmas has always meant a cheerful feast, a day to be spent with the people I cared for. One thing that struck me when I first moved to Athens was that, during the Christmas period, Greeks did not decorate their homes or churches with wooden representations of the nativity scene as we do in Italy, but with a ship. This Christmassy ship symbolizes the importance that the Aegean Sea has always had for the Greeks since antiquity; moreover, it has a religious meaning: it reminds them of Saint Nicolas, the protector of sailors and the sea, whose feast is celebrated on December 6th.

But what and how did the ancient Greeks celebrate in December? Different poleis (city-states) had different calendars and festivals; however, from Demosthenes (Apollodorus Against Neaera 59.116) and Lucian (Dial. Meret. 1.1 and 7.4.) we have references to a festival called the Haloa, which took place during this time of the year in Athens and Eleusis. The name Haloa (τὰ Ἁλῶα or Ἁλῷα, from ἡ ἅλως, ‘threshing-floor’) points to a harvesting feast in honour of Demeter, the goddess of harvest and agriculture, crops and fertility. Women would celebrate the Haloa by preparing a rich meal with dough cakes in the shape of genitalia, telling lusty jokes and bad words, singing, drinking, and dancing.

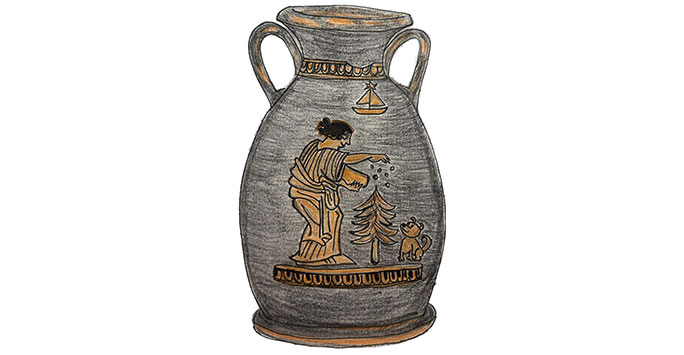

I add to this blog a drawing I made of a red-figured container (pelike) with a woman taking care of a little Christmas tree and her beloved dog. On the background, a Greek Christmas ship can be seen. My drawing wants to merge ‘ancient and modern Greek December celebrations’, as a wish to look at the future without forgetting the past. The original pelike (London, British Museum: E819) which inspired my drawing represents a woman dressed with a long-sleeved chiton and a himation knotted around her waist in the act of sprinkling (probably) seeds on four up-right phalloi. The pelike was found in Nola, in Southern Italy, and is dated to the fifth-fourth century BC.

Concluding, I would like to take a moment to thank all our contributors for the fantastic blogs they have provided us with during this year, and to wish everyone a great 2023, full of health, joy, and Classical Receptions!

Bibliography

For the Haloa and the role of women in rituals:

Dillon, M. 2016. ‘Women’s ritual competence and domestic dough: Celebrating the Thesmophoria, Haloa, and Dionysian rites in ancient Attica’ in: Matthew Dillon, Esther Eidinow and Lisa Maurizio (eds.), Women's Ritual Competence in the Greco-Roman Mediterranean. Routledge monographs in Classical Studies. London—New York: 165-181.

Goff, B.E. 2004. Citizen Bacchae: women’s ritual practice in ancient Greece. Berkeley.

Kaltsas, N. and Shapiro, A. 2008. Worshiping Women: Ritual and Reality in Classical Athens. Alexander S. Onassis Public Benefit Foundation (USA). New York.

For the Attic red-figured pelike which inspired my drawing, see the Beazley archive with related bibliography.

(last accessed on December 4th, 2022).