Dr Frederick Jones is a Senior Lecturer in the Department of Archaeology, Classics and Egyptology at the University of Liverpool. A specialist in Classic languages, Dr Jones is also an accomplished artist and is an Associate of the Royal Birmingham Society of Artists (RBSA). Find out how his work in Classics is intertwined with his art.

I have taught language and literature since arriving at Liverpool in 1989; gradually, my research has incorporated more material culture and more and more Reception material. This is especially work on art and gardens arising from research on Virgil’s Eclogues, and work on the reception of culture in Renaissance and later art. All this has increasingly found its way into my teaching of Classical literature. Another result is that there is now a significant overlap between my research and teaching, on the one hand, and my practice as an artist on the other, for as well as working as a Classicist I have a para-existence in the art world as a maker of etchings, wood engravings, and mezzotints.

I have been making prints since 2005 and have exhibited in Denmark, Netherlands, Canada, Australia, U.S., Poland, Belgium, Russia, Estonia, Malaysia, Egypt, Italy, France… and, in the UK, at the Royal Academy, the Royal Scottish Academy, Society of Wood Engravers, the Royal Engravers, Society of Scottish Artists, and the Royal Birmingham Society of Artists. This year, I was invited to take part in the ‘Female Nude: Ways of Seeing’ exhibition at Studio 3 Gallery, Canterbury and an interview with me appeared in the catalogue. Also in this year, I was elected an Associate of the RBSA.

I have been making prints since 2005 and have exhibited in Denmark, Netherlands, Canada, Australia, U.S., Poland, Belgium, Russia, Estonia, Malaysia, Egypt, Italy, France… and, in the UK, at the Royal Academy, the Royal Scottish Academy, Society of Wood Engravers, the Royal Engravers, Society of Scottish Artists, and the Royal Birmingham Society of Artists. This year, I was invited to take part in the ‘Female Nude: Ways of Seeing’ exhibition at Studio 3 Gallery, Canterbury and an interview with me appeared in the catalogue. Also in this year, I was elected an Associate of the RBSA.

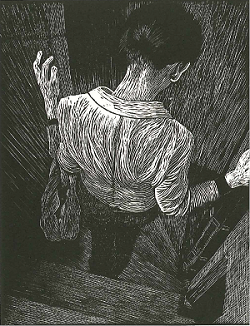

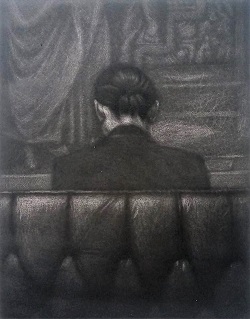

On the surface, my prints are chiefly urban and very often figurative; I aim to catch the textures and effects of light of the everyday world, but I am also keen to incorporate some of the abstract patterns we are surrounded by – grids and spirals are represented by windows, staircases, bathroom tiles, paving stones and so forth. Since so much of our life is framed by, and recorded in, grid and table structures this formal element hovers between architecture and metaphor. The main influences on my work have been Dutch and Northern European painters and printmakers, especially Vermeer, Eckersberg, Hammershøi, Richter.

I work chiefly in mezzotint and wood engraving. Printmaking has been practised since the renaissance, but wood engraving really took off at the end of the eighteenth century. Mezzotint was practically invented by Prince Rupert of the Rhine, the Duke of Cumberland (who also fought as a Royalist cavalry commander in the English Civil War), and was developed significantly in the nineteenth century by Peter Ilsted, Hammershøi’s brother-in-law. These two media are quite different from each other. Mezzotint (sometimes called manière noire) is a medium naturally prone to darkness, but, for me, in a successfully achieved mezzotint there is also paradoxically a glow which comes through the dark of the print. The process of gradually burnishing down a roughened copper plate is like sketching over and over again in the same place so that the lights emerge more and more strongly; at the same time this constant going over gives a texture of atomic strokes of light and catches not just a moment, but a moment that has been superimposed on itself over and again. An achieved mezzotint captures a moment that contains more than itself.

I work chiefly in mezzotint and wood engraving. Printmaking has been practised since the renaissance, but wood engraving really took off at the end of the eighteenth century. Mezzotint was practically invented by Prince Rupert of the Rhine, the Duke of Cumberland (who also fought as a Royalist cavalry commander in the English Civil War), and was developed significantly in the nineteenth century by Peter Ilsted, Hammershøi’s brother-in-law. These two media are quite different from each other. Mezzotint (sometimes called manière noire) is a medium naturally prone to darkness, but, for me, in a successfully achieved mezzotint there is also paradoxically a glow which comes through the dark of the print. The process of gradually burnishing down a roughened copper plate is like sketching over and over again in the same place so that the lights emerge more and more strongly; at the same time this constant going over gives a texture of atomic strokes of light and catches not just a moment, but a moment that has been superimposed on itself over and again. An achieved mezzotint captures a moment that contains more than itself.

Line is much more obvious in wood engraving than in mezzotint; every wood engraving is an experiment with a new approach to line. Sometimes the people in my wood engravings are like nets of sine waves, flames, water, or muscle-fibre, and there is a game with making images that flow and ripple out of the very dry material of wood. As well as line, the interweaving of pure blacks and whites in wood engraving generates a sort of ‘sparkle.’ Of course, the people in both the engravings and mezzotints are also living beings with their own pasts, presents, and futures and their own thoughts and feelings.

Find out more

- Study in the Department of Archaeology, Classics and Egyptology at the University of Liverpool

- Learn more about Dr Jones