In the run up to the conference ‘All the World’s a Stage’, Scott Clawson, one of the organisers and a PhD student in the department of English, reflects on lost plays and the importance of performance in helping theatre to endure, from Ben Jonson and Thomas Nashe to our own pandemic times.

How many great plays have we lost because, for one reason or another, they fell out of the performance repertoire of a particular theatre group? What sort of performance would we have got out of the players if they knew that they were to be the last in recorded history to act out those lines? It seems impossible to imagine now, in the age of internet archives, metadata, and the cloud, that a piece of published literature could ever go ‘missing’. Indeed, a very brief search on a popular online bookseller yields the opportunity to purchase texts as old as 1500, and it would be no great difficulty to find self-published works by hitherto unknown modern authors, writing exclusively through social media or blogs. If the internet can find it, it’s there to be read – and it’s there for good.

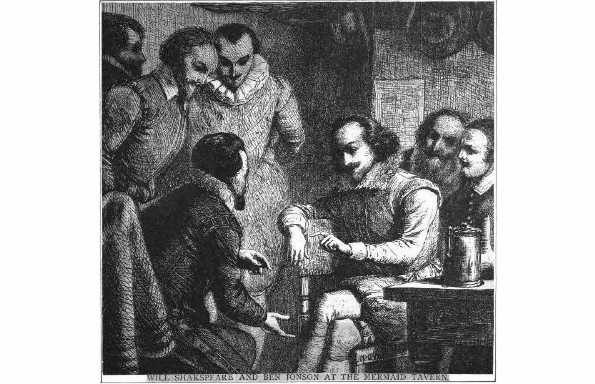

However, once upon a time, having a physical copy of a published text was no guarantee of its lasting influence or existence. The Isle of Dogs (which bears no relation to Wes Anderson’s 2018 film) is one of history’s more infamous ‘lost plays’. Written by Ben Jonson and Thomas Nashe in 1597, The Isle of Dogs was suppressed as quickly as it was performed. The exact reason as to why this particular play was censored is also lost, but it seems clear that Jonson and Nashe had written a play which poked fun at the wrong people, or at the wrong time. The immediate reaction was so vitriolic that Nashe attempted to distance himself from the play, referring to it as an ‘imperfit Embriõ’,1 and claims that he was only responsible for ‘the induction and first act of it, the other foure acts without my consent, or the least guesse of my drift or scope’.2 The result of his ‘encrease’, a monstrous birth, caused him to remark that it was ‘no sooner borne but I was glad to run from it’3 – very appropriate for an author whose involvement in this play (and other scandals) had forced him to flee to Great Yarmouth.

There remains no extant text of The Isle of Dogs. What little we do know about it has come to us through references to it in other places, such as Nashe’s pamphlets or the letters of government officials. It is almost certain that we will never be able to read what Jonson and Nashe wrote that was so offensive, despite the vast archives we have at our fingertips, and, thus, we will also never see the play performed.

This latter element, of performance, is often crucial to the longevity of a particular play. There may be readily available physical copies of a particular text, but, without sufficient interest in its performance, or lacking a recent publication, it too may disappear from our immediate view.

One such example of this is St. John Ervine’s The Lady of Belmont, first published in 1923, but last published in 1940.4 This play seems like it was set up with all of the right advantages: it was written by a well-known playwright of the period, it is a direct sequel to one of Shakespeare’s most famous plays, The Merchant of Venice, and initial reviewers found that they would ‘infinitely prefer it to another revival’5 of the original. Due no doubt to its relative youth, there are a number of copies in good condition of The Lady of Belmont available to purchase online. However, despite all of these pros, the play has seemingly escaped notice, even by Ervine enthusiasts and those most voracious of chroniclers, Shakespeare academics, who should surely jump at the opportunity to witness a version of ‘What happens next to Shylock?’. The playwright’s own Wikipedia page fails to mention the play at all.

There are scant few records of performances during the play’s publication lifespan, though those that can be found range from London to California and Johannesburg. Most recently, in 1960, there was a run of 12 performances at the Abbey Theatre in Dublin (which Ervine managed for a very short period in 1915–16).

Although Ervine is still considered as one of the eminent Northern Irish playwrights, there seems to be nothing which explains why this play was written, and what inspired him to conceive a sequel to The Merchant of Venice. Beyond his dislike of cruelty for the sake of pleasure, and his clear philosemitism, both of which are discussed in his 1936 travelogue, A Journey to Jerusalem, the play’s raison d'être, and anything else for that matter, is a little unclear.6 It’s clear that, despite everything that this play had going for it, without performance it slipped from our consciousness.

The ‘All the World’s a Stage’ conference, which will take place over the weekend of the 17–18 April, intends to be a medium for discussing the impact of all things theatre, including the importance of performance. During the COVID-19 pandemic, audiences have been treated to an unprecedented number of plays performed online, and access has been granted by many institutions to their catalogues of previously recorded performances. This is undoubtedly a force for good in keeping the theatre fresh in the minds of those who cannot currently attend, but also for the future of those plays, whose longevity and visibility may depend on a rich history of performance.

Though The Isle of Dogs may be lost forever, it is imperative that original works and adaptations, whether they be simple interpretations or prequels/sequels, are preserved for future generations, and there is no better way to ensure that than through performance. The Lady of Belmont may be a speculative attempt at ‘answering’ Shakespeare, but its existence implies an emotional reaction to the original play, and one that may inform both Ervine and Shakespeare scholars of the future. And who knows, if an audience is treated to a new performance of The Lady of Belmont, perhaps a future playwright will be inspired into writing their own adaptation, and continuing the vital work of theatre.

1. Thomas Nashe, ‘The Praise of the Red Herring’, in The Works of Thomas Nashe, 3 vols (London: A. H. Bullen, 1905), III, 153-226, p. 153.

2. Nashe, ‘The Praise of the Red Herring’, p. 154.

3. Nashe, ‘The Praise of the Red Herring’, p. 154.

4. St. John Ervine, The Lady of Belmont (London: George Allen & Unwin, Ltd., 1940).

5. Ervine, The Lady of Belmont, inside front book sleeve.

6. St. John Ervine, A Journey to Jerusalem (London: Hamish Hamilton, 1936).

‘All the World’s a Stage’ will take place online from 17–18 April, with a keynote from Dr Emma Whipday (Newcastle). Attendance is free. Register here.

Conference Twitter: @AllTheWorldConf

Organised by: Amy Jennings, Jack Murray and Scott Clawson, department of English, University of Liverpool

Click here to see more work on Renaissance theatre by scholars in the English department.