The Current State of Multilingualism in the UK

Proportionate to the globalisation and diversification of academic (and other) circles, increased focus has been placed on the ‘Decolonising the Curriculum’ initiative. There are numerous benefits to dissecting the power relations that shape knowledge. Unconscious biases can be identified, with students’ intellectual vision broadening to include diverse ethnic, racial, social and cultural perspectives. Students’ perceptions of academic landscapes can be widened beyond the archetypal groups expected to dominate the distribution of knowledge – and students can immerse themselves in the UK population’s increased ethnic diversity projected in the next few years (Lomax et al., 2019).

While these benefits are rarely contested, how best to put ‘Decolonising the Curriculum’ into practice requires much consideration. As the first of a two-part series, this blog explores one of the most engaging, student-centred methods in the process of pedagogical decolonisation: foreign language learning (FLL). It analyses why levels of multilingualism remain low in the UK, offering students an opportunity to take agency in overcoming their own unconscious biases against foreign languages and cultures.

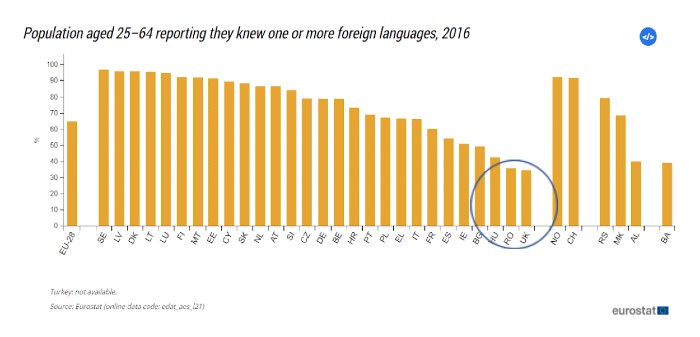

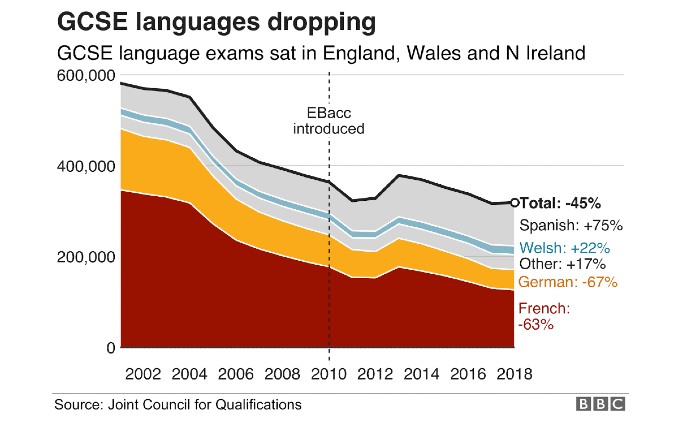

As seen above, the UK has the lowest levels of multilingualism in Europe, with roughly 35% of twenty-five to sixty-four year-olds reporting proficiency in another language (Eurostat, 2016). There are a multitude of ideological and pedagogical reasons for this imbalance. First of all, educational strategy regarding FLL has been woefully negligent. Ever since the government’s decision in 2004 to drop compulsory FLL at key stage four (GCSE level), the number of students studying foreign languages has plummeted (see below).

Emphasis on the benefits of multilingualism is virtually non-existent, and the way in which foreign languages are taught (prior to key stage five), often with an overfocus on grammar and structure rather than applicability and identity, deters many students from continuing FLL. This is particularly seen in figures of German and French GCSE language exams (below), although FLL in the UK is down across the board (Jeffreys, 2019). If significant changes to the curriculum are not made, levels of multilingualism – already the lowest in Europe – will continue to diminish inversely to the UK’s increased ethnic diversification, moulding a potentially hostile environment underpinned by cultural misunderstanding and monoglossic isolationism.

Key issues in current approaches to language learning in the UK include a lack of priority for FLL in the National Curriculum – evidenced by the minimal number of hours allocated in the UK education system compared to other European countries (Grenfell, 2002) – and the lack of relevant subject matter. By focusing language lessons on appealing, applicable topics, British students would show greater levels of interest in FLL, as they could envisage its future usefulness. The teaching of simplistic, uninspiring content – as well as excessive grammar – stems from a pedagogical overfocus on accuracy ahead of fluency, which other European nations’ education systems have circumvented by prioritising communicative intelligibility (Milton and Meara, 1998). Ideological factors also underpin the UK’s widespread monolingualism, such as the lingering jingoistic assumption that FLL is futile because others will speak English, stemming originally from British imperialism, and perpetuated by English’s present status as an international lingua franca (Phillipson, 2013).

Widespread dissemination and increased public awareness of the benefits of FLL would logically boost pedagogical interest. This, in turn, could have an understated yet significant impact on the long-lasting academic shifts towards decolonisation. Click here to read about the benefits of FLL, from improved socioeconomic opportunities to enhanced cognitive functioning.

References

Eurostat (2016) Foreign language skills statistics. Available at: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Foreign_language_skills_statistics (Accessed: 7 April 2022).

Grenfell, M. (2002) Modern languages across the curriculum. Abingdon: Routledge.

Jeffreys, B. (2019) ‘Language learning: German and French drop by half in UK school’, BBC News, 27 February. Available at: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/education-47334374 (Accessed: 7 April 2022).

Lomax, N., Wohland, P., Rees, P. & Norman, P. (2019) ‘Data and Methods for Estimating and Projecting International Migration by Ethnicity’, Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 3(1), pp. 1–23.

Milton, J. & Meara, P. (1998) ‘Are the British really bad at learning foreign languages?’, Language Learning Journal, 18(1), pp. 68–76.

Phillipson, R. (2013) Linguistic imperialism continued. London: Routledge.