This long-read blog post serves to explore some of my thoughts on the UK response to the pandemic. I would like to start by sending my well wishes to all who have lost loved ones during this time and all key workers.

Acknowledgements: I would like to thank colleagues for their kind and insightful feedback on an earlier of this blog post: Dr Firat Cengiz, Professor John Preston, Professor Kanstantsin Dzehtsiarou, Professor Lucy Easthope, Dr Mike Homfray, Dr Michael Riordan.

Coronavirus Act 2020

The Coronavirus Act 2020 received Royal Assent on 25th March 2020 after being fast-tracked through parliament in just four sitting days. It contains emergency powers to assist the country through the Covid-19 pandemic. It also provides the state with an extraordinary level of control over the everyday lives of citizens. As a Criminologist I am fascinated with how power is formed and exerted, and as a Dyslexic thinker I am keen to draw together the dots of what is happening during the ‘state of exception’ (Agamben, 2005). Agamben has shown that the state uses and abuses the use of ‘exception’ to deviate away from the rule of law (Choukroune, 2020; see also Preston et al, 2014).

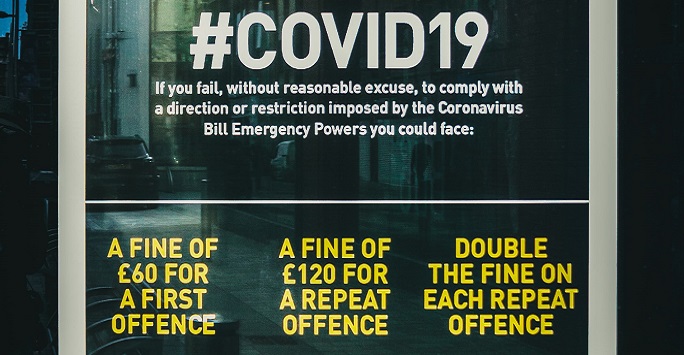

The Act saw a public health crisis being treated as a criminal justice issue with Fixed Penalty Notices (FPN) issued for breaches of the rules. There was much confusion for what constituted law and what constituted guidance, with the guidance deliberately being more stringent than the law. Prominent human right barrister Adam Wagner spent much time on twitter educating the public on the rules as they changed.

‘Lockdown’ was the first new terminology, the term is taken from the prison regime. We have had ‘flattening the curve’, ‘circuit breakers’, ‘tiers’, ‘rule of 6’, ‘bubble’, ‘pinged’,and we have become accustomed to face masks, arrows on floors, perspex screens and having to check what the current law permits before making plans and interacting with our loved ones. We had to decide what a ‘reasonable distance’ was in order to travel for exercise and consider whether we were allowed to sit on a bench during, or after, exercise or leave the house for another ‘reasonable excuse’. This deliberately confusing and often subjective labyrinth of rules has been difficult to keep up with, with Adam Wagner calling for clarity in January 2021, noting that the rules had, at that point, changed 64 times (Syal, 2021). Wagner, of Doughty Street Chambers, stated that new national regulations, local regulations, regulations on face coverings or rules on travel quarantine have passed into law on average every four-and-a-half days since the first restrictions were introduced in Spring 2020.

It is important to note that the government response is an unexpected deviation from what disaster planners thought the legal response would be for a pandemic. A pandemic was our most likely national risk and had been extensively planned for (National Risk Register 2017, 2020; see also Bennett Institute for Public Policy, 2020). [I would like to thank Professor Lucy Easthope for her expertise here].

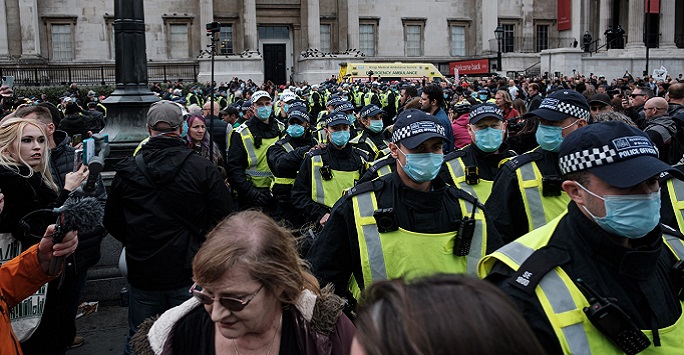

Policing the Pandemic

Therefore we can see that it is not simply a case of ‘follow the rules’ but rather understanding what the rules are at any point. Examples from the media made for fascinating teaching and writing material but did feel dystopian. A key example of this was Derbyshire Police using drones to take footage of dog walkers in the Peak District during the first lockdown in March 2020 (BBC, 2020).

A further example is South Yorkshire Police having to issue an apology after a sergeant tweeted: “Tonight has seen us checking people’s reasons for being on the streets. Between essential saunter in jeans as exercise, an essential trip to the shops for egg custards and essential trip to the cash machine for £20 to use in the morning, we’ve offered a lot of advice” (Cumber, 2020).

Another example from Derbyshire Police consisted of them dying a lagoon black in order to prevent gatherings at beauty spot Blue Lagoon stating: "...However, the location is dangerous and this type of gathering is in contravention of the current instruction of the UK Government. "With this in mind, we have attended the location this morning and used water dye to make the water look less appealing” (Minelle, 2020).

Clearly such restrictions, and the policing of such, have caused great concern for lawyers and criminologists (Chakroune et al, 2021).

Whilst few will deny that we are in the midst of a serious public health crisis (and globally, a humanitarian disaster) many of us have questioned the legitimacy and effectiveness of making a public health issue a criminal justice matter. Critics include Professor Stefan Baral (Public Health) who specialises on network and structural inequalities in infectious diseases. Professor Baral has a brilliant talk named ‘An Equity-Lens to Characterize COVID-19 Transmission & Inform Interventions’.

A state never exerts its power equally across its citizens, those who are already marginalized and susceptible to various forms of discrimation will be policed disproportionately. Dinou, a Black woman, was incorrectly prosecuted under the Coronavirus Act, “Deputy Chief Constable Adrian Hanstock said: “There will be understandable concern that our interpretation of this new legislation has resulted in an ineffective prosecution” (Boyd, 2020).

Dinou was wrongly prosecuted after ‘loitering between platforms’ at Newcastle train station. Her conviction was reversed by Section 142 of the Magistrates Court Act 1980

which allows a Magistrates Court to reverse a conviction “if it appears to be in the interests of justice to do so” (Pump Court Chambers, 2020).

Covid Courts

Barrister Matthew Scott wrote that £10,000 fixed penalty notices, issues by decree, are a legal abomination. Scott argues that the pandemic has been policed in an inappropriate manner (Scott, 2020).

Few people are aware that alleged breaches of the regulations are being dealt with via dedicated Covid courts which represent a huge threat to our system of law. Covid offences are being dealt with via Single Justice Procedure. Kirk argues that in the Westminster lockdown breach cases lists of results have not been issued to the press despite repeated requests, while two weeks worth of prosecutions were hidden entirely after court staff forgot to send out the details. An open justice safeguard that journalists can inspect court papers on request has also been ignored (Kirk, 2020).

The House of Commons Justice Committee on Covid-19 and criminal law took oral evidence on the 22nd April 2021. The transcript is available here (House of Commons, 2021).

Concerns raised included the tendency to legislate at very short notice persistently throughout the pandemic. Regulations have been drafted and published sometimes immediately before they are due to come into force, sometimes a matter of hours and sometimes a couple of days before (Harnsard Society, 2021). This makes enforcement very difficult. The second main concern raised has been around the procedure that the Government has chosen to adopt for making these regulations. Typically, they have used the emergency procedure under the Public Health Act, which means that the legislation is not laid before Parliament in advance, and it certainly is not debated in advance. Rozenberg states that: “The former head of the government legal department said that bad legislative habits had become ingrained and that the rule of law would be at risk if people could not find laws that bound them. He emphasised that the police needed to understand the difference between policies announced by ministers at press conferences and laws made under the authority of parliament” (Rozenberg, 2021).

Barrister Pippa Woodrow of Doughty Street Chambers sets out how the emergency coronavirus laws represent the most significant interference with our liberty, and has campaigned into a review of the fixed penalty notices (Woodrow, 2020).

Indeed, In May 2021 all 270 prosecutions under the Coronavirus Act were withdrawn or overturned in court after innocent people were convicted (Dearden, 2021).

This is extremely worrying, particularly given that 115,203 Fixed Penalty Notices (FPNs) were issued under the Coronavirus Act between 27th March 2020 and 16th May 2021 (Brown and Wade, 2021).

Transferring Risk

As Criminologists know, it is the visible who are disproportionately policed. It is why we see so much knife crime in the newspapers but not as much white collar and state crime for instance. The categories of gender, class, race, sexuality, age and disability are usually much considered in the discipline. These must be considered during the pandemic to understand why some people are unfairly treated by the Coronavirus Act. Those living in large comfortable houses, able to transfer their risk to precarious and lowly paid workers in warehouses, food distribution and retail, (amongst many others) have not experienced the same pandemic as those living in cramped housing and/or multi-occupancy housing with no access to outdoor space or leisure (Hall, 2021).

Professor John Preston and Dr Rhiannon Firth have rightly called this the front line in the war on the working class, with rules drawn up to protect the middle class and demonise the working class. We can see this through moralising discourses in the media, placing personal blame on those visible in public space for ‘breaking the rules’. Photos of congested beaches and busy parks were de rigueur during the pandemic. The opportunities for mutual aid was limited due to the restrictions placed on citizens interacting with one another. We could have assistance during lockdown one for instance, but only if we paid for it. Preston & Firth have been critical of the working class having been disproportionately harmed by lockdown measures, stating: “In the media, international and business travel received barely a whisper, but pictures of people in parks were a cause for national outrage. The middle classes may have a nice garden to relax in, but if you live in an urban block of flats where else are you meant to go?. Authoritarian policing has targeted working class people, particularly if they are Black or Asian. Bizarrely, the left and even some anarchists are advocating more restrictions on freedom” (Preston and Firth, 2021).

Health/power/criminality-nexus

I have co-authored a journal article to be published in September 2021 with a colleague in medicine, ‘The health/power/criminality-nexus in the state of exception’ (Ahearne and Freudenthal, In Press). In the article we argue that the positioning of the ‘other’ as a dangerous vector of disease is a long-standing trope. This has existed both in racial terms, such as the 1905 Aliens Act, and for others positioned as on the outliers of society, such as sex workers, under the Contagious Diseases Acts 1864, 1866, 1869 (Hamilton, 1978). We also argued that the public health system has long been used as a system of control, alongside its self-described role as existing for the betterment of population health. Similarly, other aspects of our health system have long functioned both as a foundational part of the welfare state, and as key perpetrators of racial injustice are part of the carceral state. During the pandemic the healthcare system has increasingly been used as a justification for advancing a state apparatus of biopower, and has experienced little resistance from the organised left. This is not to say that we should ignore the very real pandemic, but rather, that as critical social scientists we must critique mis(uses) of power and present a nuanced and conflicting account of harms and ethical considerations.

Likewise, the push for mandatory vaccinations ignores the fact that those in the most precarious positions in society are less likely to have the vaccination. These include those with serious mental illness, those in poverty, those without documentation, or otherwise marginalised people, and those less likely to have access to a digital device in order to access a covid passport. Covid certificates would mean that health inequalities will become deeper (Baker and Butler, 2021) as will access to public spaces.

War on ‘the other’

The war on dissent can be seen in terms of the crackdown on legitimate concerns or critiques of the powers used during the pandemic. One example being the ‘blacklisting via the backdoor’ of journalists who submit Freedom of Information requests (Geohagen, Corduroy, Amin, 2020).

Police, Crime, Sentencing and Courts Bill

This must be read alongside other developments. The Police, Crime, Sentencing and Courts Bill (2021) represents serious changes to democratic rights in the UK including the right to protest and a threat to the way of life for Traveller communities.

Colleagues in Criminology Dr Roy Coleman and Beka Mullin-McCandish have blogged in detail about the bill.

Nationality and Borders Bill

A further bill to consider is The Nationality and Borders Bill (2021) which is an attack on the rights of those seeking asylum. The new Bill also paves the way for potential offshore processing centres for refugees, akin to those set up by the Australian government on Nauru and Manus Island (Qureshi & Mort, 2021; Jarbour 2021)

The British sea rescue charity Royal National Lifeboat Institution (RNLI) has spoken out against the Bill (Mellersh, 2021). Legal commentators have argued that Clause 38 of the bill potentially criminalises rescues of asylum seekers (Marine Industry News, 2021).

The conflation of criminality with asylum has been a powerful tool to further this advance. In October 2020 the Secret Barrister [ insert link https://twitter.com/BarristerSecret ] accused the Home Office of spreading misinformation regarding asylum seekers and criminality. “More #FakeLaw from @pritipatel’s fundamentally dishonest Home Office. “Convicted foreign criminals” have absolutely *NOTHING* to do with the asylum system. The @ukhomeoffice is spreading false information and should immediately issue a correction and an apology” (Mellor, 2020).

The attacks on the human rights of those seeking asylum (The UN Refugee Agency, 2021) are enabled by dehumanisation through constructing them as vessels of disease. We know that the moral panic surrounding people a ‘vector of disease’ has always fallen on marginalized groups such as sex workers, the AIDS pandemic is testimony to that. At such crisis times, an ‘other’ is a useful political tool to attach blame to. The visceral threat of a deadly virus commands great fear, and this is a powerful tool to eradicate the ‘other’. It is important to note that this increased hostile landscape against migrants is a global issue that has been exacerbated by the pandemic. Cosse notes that at a July 19 press conference, Greek police on the island of Lesbos announced a criminal case against 10 foreign nationals, four of whom work for nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), the state alleging that they helped migrants enter Greek territory illegally, conducted espionage, and complicated investigations by the Greek authorities (Cosse, 2021). It is no surprise that this intensification against the rights of migrants and refugees has occurred whilst the world is in fear of a dangerous virus; at this time, bodies are easily positioned as risky contagion who must be expelled for ‘our’ safety.

Abjection and Dirt Discourse

Ahmed argues that feelings such as disgust are closely linked to social abjection; rooted in cultural phenomena associated historically with particular bodies (Ahmed, 2014). Immigration raids during the pandemic can be read in this way ( Atkinson, 2021). Ahmed argues that to feel something, or someone, is disgusting is to physically 'cast them out’ (Ahmed, 2004). Disgust work maintains boundaries and legitimizes punitive responses to ‘get rid’ of the dangerous diseased ‘other’ (Miller 1997; Douglas, 1995; Kristeva, 1992; Sibley, 1995). Tyler argues that abjection is about the need to create “a space, a distinction, a border, between herself and the polluting object, thing, or person” (Tyler, 2007).

This framework of understanding is invaluable when looking at the attacks on the most socially excluded and vulnerable. Asylum seekers housed in Napier barracks were housed in dormitories, contributing to a Covid-19 outbreak where nearly 200 people contracted the virus (BBC, 2021). Mr Justice Linden ruled that the decision by the Home Office to house the people seeking asylum in the squalid conditions was unlawful. Once again we can see that the instruction to ‘stay at home’ does not work if you do not have a home and/or are in unsafe cramped living arrangements. Much of the guidance was to self-isolate from their own families in another room and to use a different bathroom (Public Health Agency, 2021). Clearly this was considered from a privileged middle-class perspective and did not account for the majority of families and living arrangements where this would not be possible.

The Runnymede Trust argues that Many minority ethnic individuals find it harder to self-isolate because of the conditions in which they live and work. “Nearly one third of Bangladeshi households and 15 percent of Black African households are classified as overcrowded, compared to only 2 percent of white households. Bangladeshi and Black African households also have only 10p for every £1 in savings held per White British household, and are more likely to expect difficulty paying their bills in coming months, meaning taking time off work to self-isolate is often unaffordable. Self-isolation is already difficult – less than 20% of people with Covid-19 symptoms isolate appropriately – but poor housing and financial precarity makes it almost impossible without additional support” (Treloar, 2020).

Here we can see that it is not a ‘failure to comply’ with rules, but an inability to meet the requirements due to structural inequalities that have not been considered by those devising the Covid response. In their report, The Runnymede Trust have stated that: “We are disturbed to see entrenched disproportionalities in the criminal justice system playing out in the enforcement of emergency Covid-19 legislation” (Runnymede Trust, 2021).

Official Secrets Act

Further evidence of the war on dissent are the plans to reform the Official Secrets Act; changes that will have severe consequences for the freedom of press that is integral to a democratic society (Wahl-Jorgensen, 2021).

The Press Gazette submitted a letter to the government consultation on reforms to the Official Secrets Act, stating that protections for whistleblowing should be strengthened, not weakened, because we all benefit from it (Mayhew, 2021).

Judicial Review Bill

Alongside this, we must consider the dangers of the Judicial Review Bill (Ministry of Justice, 2021). Stephanie Boyce, president of the Law Society, which represents solicitors in England and Wales, said: “There is a great deal here that should ring alarm bells for people who come up against the might of the state. The MoJ suggests the bill may set a precedent for the government to give itself the power to remove certain types of cases from the scope of judicial review, which would effectively spawn a new breed of ouster clause. There are rare, exceptional circumstances when it is appropriate for the state to circumvent the courts, and only with strong justification. Parliament will need to think very carefully about the potential impact of any such proposals on the rule of law” (Siddique, 2021).

Conclusion

Covid-19 represents a real and ongoing threat globally. However under this state of exception the government is undertaking a power grab and changing how democracy works. As a Criminologist I am concerned about living with constant biosurveillance, threat of detention, ongoing border restrictions and ‘closures’, threats of vaccine certificates, and the erosion of trust. The fear presented by the virus is being weaponized to justify tougher border controls; the threat of processing asylum seekers offshore; the treatment of protesters. Likewise, the rules have not been applied equally, with those most vulnerable to the state’s power being disproportionately punished. The pandemic represents a very uncertain and fragile time for law and governance, with decreased opportunities of holding the government to account. In my paper with Freundenthal (In Press, 2021) we argue that more disciplines need to come to the table to aid understanding of complex social matters.

The author

Gemma has 20 years experience of the sex industry and has been teaching in Higher Education for 9 years. One of Gemma’s current research projects is working with colleagues in medicine and disaster planning, interrogating the health/power/criminality-nexus in relation to the pandemic. Much of her work focuses on moralising discourses and how people are constructed as the 'other'. Gemma is keen to continue developing multidisciplinary responses with colleagues internationally. Having entered academia via a non-traditional trajectory, Gemma has a strong commitment to widening participation and creating a more inclusive academy, placing value on lived experience and different ways of knowing.

Gemma’s staff profile

Twitter: @princessjack

Blog: www.plasticdollheads.wordpress.com

References

Agamben G. (2005) State of Exception, translated by Kevin Attell, Chicago: The University of Chicago Press

Ahearne, G. Freudenthal, R. (In press, 2021). The health/power/criminality-nexus in the state of exception, Journal of Contemporary Crime, Harm and Ethics

Ahearne, G. (2021). ‘The Spirit of Lockdown’, Plasticdollheads, June 13th 2021.

Ahmed, S. (2014). The cultural politics of emotion. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

Atkinson, M. (2021). Immigration raids don’t work – they just leave communities scared and divided, 20th May 2021, INews.

Baker, S., Butler, D. (2021). Forcing people to prove their Covid status will only widen the UK’s existing health inequalities, June 7th 2021, INews.

BBC. (2020). Coronavirus: Peak District drone police criticised for 'lockdown shaming', 27th March 2020.

BBC. (2021). Napier Barracks: Housing migrants at barracks unlawful, court rules, 3rd June 2021.

Bennett Institute for Public Policy. (2020). The history of emergency legislation and the COVID-19 crisis, University of Cambridge.

Brown, J., Kirk-Wade, E. (2021). Coronavirus: Enforcing Restrictions, House of Commons Library.

Choukroune, L., Chapman, S., Tyson, J. (2021). Democracy and Policing Under Pressure. Life Solved Podcast, University of Portsmouth.

Choukroune, L. (2020). When the state of exception becomes the norm, democracy is on a tightrope, The Conversation, April 27th 2020.

Cosse, E. (2021). Greek Authorities Target NGOs Reporting Abuses against Migrants, Human Rights Watch, July 22nd July 2021.

Craig, P. R. (2021), Judicial Review, Methodology and Reform, June 28, 2021, Forthcoming, Public Law January 2022, Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3875313 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3875313

Cumber, R. (2020). South Yorkshire Police apologises over 'wrong kind of jeans for exercise' message, 1st May 2020.

Dearden, L. (2021). All 270 charges brought under Coronavirus Act wrongful, official review finds, The Independent, 14th May 2021.

Douglas, M. (1966). Purity and Danger, An Analysis of Concepts of Pollution and Taboo, London: Routledge and Kegan Paul

Geohagen, P., Corderoy, J., Amin, L. (2020). UK government running ‘Orwellian’ unit to block release of ‘sensitive’ information, Open Democracy, 23rd November 2020.

Hall, S.A. (2021). The Pandemic Middle Class The Unequal Impact of Test and Trace, Byeline Times, 22nd July 2021.

Hansard Society, (2021). Coronavirus Statutory Instruments Dashboard.

House of Commons (2021). Justice Committee Oral evidence: Covid-19 and the criminal law, HC 1316, Tuesday 20th April 2021.

Jarbour, B. (2021). It is astonishing to witness the Australian 'border wars' given our Covid response so far, Guardian, 7th January 2021.

Judicial Review and Courts Bill. (2021). House of Commons. Bill 152. London: The Stationary Office

Kirk, T. (2020). Covid rule breakers targeted in secret London prosecutions, Evening Standard, 16th October.

Kristeva, J. (1982) The Powers of Horror an Essay on Abjection, New York: Columbia University Press

National Risk Register. (2020). HM Government.

Nationality and Borders Bill. (2021). Parliament: House of Commons. Bill 141. London: The Stationary Office

Marine Industry News, (2021). RNLI issues defiant statement regarding migrant rescues, 12th July 2021.

Mayhew, F. (2021). Press Gazette’s submission to Government’s consultation on Official Secrets Act reforms, 23rd July 2021.

Mellersh, N. (2021). British migrant charity responds to criticism amid publication of the UK's Nationality and Borders Bill, Info Migrants, 7th July 2021.

Mellor, J. (2020). Patel’s ‘rotten to the core’ Home Office argues with Secret Barrister and it doesn’t go well, The London Economic, 10th May 2020.

Minelle, B, (2020). Coronavirus: Derbyshire police dye Buxton 'Blue Lagoon' black to deter gatherings, 28th March 2020.

Miller, W. I. (1997). The Anatomy of Disgust, London: Harvard University Press

Scambler, G., Peswani, R., Renton, A., Scambler, A. (1990). Women Prostitutes in the Aids Era, Sociology of Health & Illness Vol. 12 No. 3, pp. 260-273

Scott, M. (2020). Lockdown Policed Entirely the Wrong Way, The Telegraph.

Sibley, D. (1995). Geographies of Exclusion: Society and Difference in the West, London: Routledge

Siddique, H. (2021). Law Society sounds warning against judicial review bill, Guardian, 21st July 2021.

Syal, R. (2021). English Covid rules have changed 64 times since March, says barrister, The Guardian, 12th January 2021.

Treloar, N. (2020). Ethnic inequalities in Covid-19 are playing out again – how can we stop them?, 19th October 2020, Runnymede Trust Blog.

Tyler, I. (2013). Revolting Subjects, Social Abjection and Resistance in Neoliberal Britain, London: Zed

Policing, Crime, Sentencing and Courts Bill (2021). Parliament: House of Commons. HL Bill 40. London: The Stationary Office

Preston, J. Firth, R., (2021). The pandemic is the new front line in the war on the working class, The Big Issue, 2nd March 2021.

Preston, J., Chadderton, C., Kitagawa, K. (2014) The ‘state of exception’ and disaster education: a multilevel conceptual framework with implications for social justice, Globalisation, Societies and Education, 12:4, 437-456, DOI: 10.1080/14767724.2014.901906

Public Health Agency, (2021). How to self-isolate in a shared house if you or someone you live with has coronavirus.

Pump Court Chambers. (2020). Lessons to be learned from the Marie Dinou case, 7th April 2020.

Qureshi, A., Mort, L. (2021). Nationality and Borders Bill: the proposed reforms will further frustrate an already problematic asylum system, London School Economics Blog.

Rozenberg, J. (2021). ‘Covid and the criminal law Journalists and a barrister speak truth to power’, A Lawyer Writes, April 21st 2021.

Runnymede Trust, (2021) England Civil Society Submission to the United Nations Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination.

UN Refugee Agency. (2021). After UK asylum bill debate, UNHCR urges MPs to avoid punishing asylum-seekers, 21st July.

Wahl-Jorgenson, K. (2021). Official Secrets Act: home secretary’s planned reform will make criminals out of journalists, July 21st 2021, The Conversation.

Woodrow, P. (2020). Coronavirus fixed penalty notices: time to review, July 2020, Legal Action Group.