We sat down with Dr Mike Homfray, a lecturer in the Department of Sociology, Criminology and Social Policy, to talk about the meaning of Pride.

Flipping through a chat board I contribute to; I did a double take when noticing a rainbow backdrop on a shared Tweet from a right-wing blog not known for its support for LGBT rights. It appears that the rainbow is always with us, with its brief confiscation by the NHS appearing to have subsided, and the advent of June meaning the beginning of Pride Month and rainbows liberally adorning corporate logos, from BMW, to police forces, to football clubs.

The idea of having a month dedicated to Pride is relatively recent but Pride itself has been well-established for some 50 years in the USA. Often seen as the ‘birth’ of the LGBT+ movement, the riots following raids at New York’s Stonewall Inn led to the establishment of events set for the end of June 1970, in New York, Los Angeles and Chicago, which, as Peterson, Wahlström and Wennerhag’s 2018 study noted, “combined politics with celebration and party. The New York march as well as the Los Angeles event combined elements of traditional protest politics with celebratory festive elements”. London followed close behind, with the first London Gay Pride event taking place on the 1st of July 1972, organised by the Gay Liberation Front, reflecting the radical wing of the gay social movement, dedicated to overthrowing the prejudices both social and legal affecting sexual minorities, and often with a more thoroughgoing critique of the gender order and ‘familial ideology’ with its assumptions of family as heterosexual married couple with 2.4 children!

With the odd exception (a Pride march in Huddersfield in 1981, to protest about the well-publicised raids on the only local gay club, the Gemini, by the police), Pride became an established yearly event, held in London, and attracting a national audience. I recall organising a coach trip from Huddersfield, where I lived at the time, down to Pride in 1990, with a homophobic coach driver whose unease was all too obvious, and rather taken advantage of by one of our group, who had decided to attend in drag. My first Pride was in 1986, a quick trip down from Essex and even now I recall how exciting it felt, just to be with so many other ‘people like me’ and the atmosphere which did manage to combine protest and party.

The legal situation at the time, with discriminatory legislation still in place and the introduction of section 28, the legislation which prevented ‘promotion of homosexuality’ and teaching about ‘pretended family relationships’ in schools, and the emergence of the AIDS crisis, meant that the need to carry on protesting was all too apparent, and while the party element was important (we really needed a bit of fun in those dark days) there was always an awareness that there was still a mountain to climb and so the march (not ‘parade’) was the central element of activity, although there was always a degree of understanding that the audience for the two elements of the event were not identical.

Regional and local Prides began to emerge at about the same time, with Manchester’s event being launched in 1985, as part of the emerging ‘Gay Village’ regeneration, promoted by a specific charity established to organise the event – known until 2007 as ‘Mardi Gras’. Liverpool’s attempts to launch a similar event proved rather more problematic - the story of this is covered in my book, ‘Provincial Queens’ (2007) – but since 2010, an annual event has been held in the city centre. One contrast between the Manchester and Liverpool events is that with one exception when a small charge was levied, the Liverpool event is free, whereas a full-price standard ticket for the full weekend Manchester event in 2019 was priced at £71, with VIP access costing as much as £275.

The concern about the costs of attending the event are not new and are part of a more wide-ranging debate as to what the purpose of Pride actually is, and this can be considered by raising three questions. First, what is Pride for? Second, who is it for? And third, who benefits?

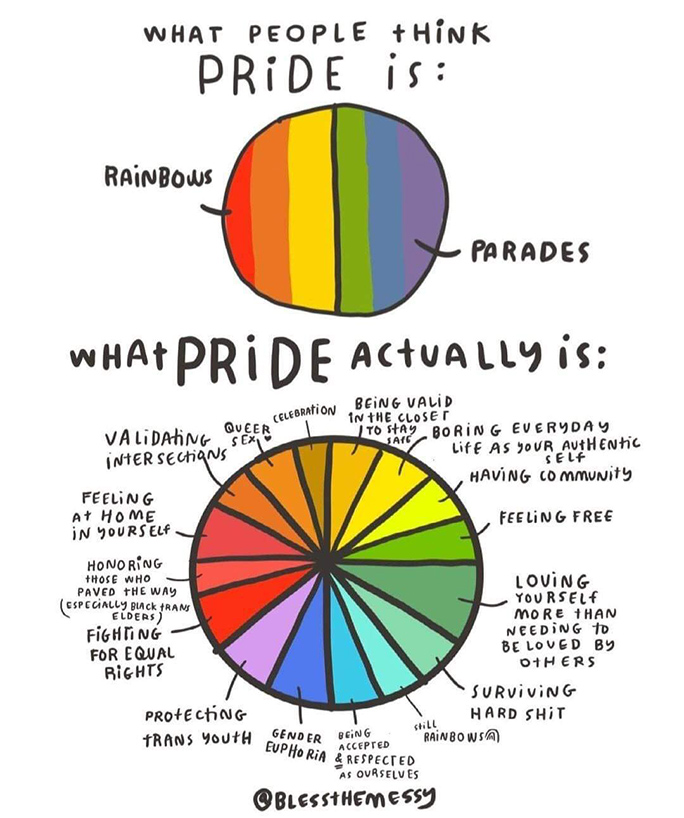

The first of those questions immediately raises queries as to what we mean by Pride. Is it the large-scale events, the idea of a ‘month’ (an American import), or more of an opportunity to focus on LGBT issues and to take advantage of something which appears to have been embraced by the mainstream alongside many other ‘days’ or ‘months’ to highlight a specific issue? It could well be all three of those things, but even a cursory consideration of the first of those issues raises questions of controversy. These are not new debates, either – the film Pride had a scene where the organisers of London’s Pride event in 1985 wanted overtly political groups to be very much in the background, so not to “frighten the horses” The issue of to what extent Pride is primarily politics or party has never been settled. The many legal changes won by the LGBT movement have perhaps taken the edge off the need to have a prominent political presence, although some issues related specifically to trans people remain an active issue of debate, so how important is it to have large scale public events which emphasise the existence of LGBT people who are no longer forced to be invisible or closeted? Should the ‘march’ element of a Pride event be rebranded as a ‘parade’ with the emphasis on providing a carnival of entertainment, with corporate floats alongside participation by community groups? Or is the reality still that those hard-won rights may remain fragile, and despite great advances, there are still people living a lie, and the essentially political nature of the identity of minority sexualities will never go away?

Who is Pride for? Is it primarily an event for LGBT people themselves, organised by them, for them, or is it an opportunity for allies to show solidarity and partake in public events along with their LGBT friends? Do these two things have to be in conflict? Again, this reflects longstanding debates as to the need to have specific social venues for LGBT people, often discussed in the context of commercial zones such as Manchester’s Gay Village, with the question of whether the Village has been colonised by straight people, often with the very best intentions, but the effect being that the Village is no longer very Gay anymore. Even the reference to ‘Pride’ without the LGBT+ is controversial. Is it no longer an LGBT event, but part of a yearly marketing programme controlled from outside the LGBT community? To what extent should activities be primarily for LGBT people and should the ‘public image’ of the community be something of concern (the presence of costumes which might be considered risqué or associated with sexual practices such as BDSM regularly arouse contrasting views, with issues of to what extent events should be ‘family friendly’ on the agenda).

There are also questions of internal conflict within the LGBT community. High ticket prices for some Pride events have led to accusations that economically deprived LGBT people are being marginalised and effectively prevented from participating in events which are supposed to bring different parts of the LGBT community together. Within that umbrella, there are those who want to remove the ‘T’, viewing trans people and their gender identity issues as separate from sexual orientation. This has been evidenced by radical feminist lesbian groups attempting to disrupt Pride events, and organisers removing them in consequence On the other side, trans activists and most of the LGBT movement involved with Pride events argue that those lesbian feminists are transphobic and have no place within a Pride where trans equality is not something to be questioned.

More broadly, who benefits from Pride? It is not overly cynical to conclude that commercial concerns view Pride as a marketing opportunity, but hard not to be cynical when its rainbow-clad insignia is only rolled out in countries where association with LGBT people may be considered financially and politically advantageous. Marxist writers like Hannah Dee wrote back in 2010 that gay people had been rebranded as “citizen-consumers” with the pink pound and the growth of the pink economy viewed as an ideal opportunity to get us all to spend more money and to rebrand empowerment as something related to the spending power we have within market capitalism. Dee uses the shift of emphasis of Pride events from the overtly political to the commercial as an example of this, referring to the “once militant commemoration of the Stonewall riots …replaced by a corporate sponsored day out”. Those who benefit are the companies who take advantage of being associated with Pride, and questions have long been raised as to how much these organisations are putting back into the LGBT community. From brewery-owned bars attracting a gay clientele, to the multinationals including same-sex couples as part of its marketing exercise, how much money is being made, and how little is then being directed towards LGBT communities? At a time when the application of austerity saw countless small projects disappear, this is something which has not been satisfactorily answered. Conversely, advocates of the market will argue that Pride and indeed, LGBT rights and LGBT people more broadly, benefits from greater individual freedom, and markets do not discriminate on the grounds of sexuality, and so a commercially driven Pride is simply evidence that LGBT people have entered the mainstream, and this should be welcomed.

In the wake of recent events, Pride has become, for the second year running, something of a virtual affair. To what extent this hiatus will see any sort of return to asking some very basic questions about what Pride is for and how it can be best realised is uncertain, given that most of the questions being raised are not new, and are unlikely to be met with any sort of consensus view in response.

Dr Mike Homfray runs the module 'Sexualities in Society'. If you are interested in studying at the Department of Sociology, Criminology and Social Policy, find out more information here https://www.liverpool.ac.uk/law-and-social-justice/blog/sexualities-in-society/