As we continue our #MyFirstPaper campaign, this week we speak with Professor Graham Kemp about his first paper he published in 1984. Graham is a Professor of Metabolic and Physiological Imaging from the Institute of Life Course and Medical Sciences.

What was the title of your first paper?

The title of My First Paper was Theoretical Aspects of One-Point Calibration: Causes and Effects of Some Potential Errors, and their Dependence on Concentration My First Paper was published in 1984.

It preceded my academic career, but in a way it started it. It’s an odd story.

I was a junior doctor (roughly ST2 in modern terminology) in Chemical Pathology. After an excellent medical undergraduate training, followed by an old-school pre-registration year which I usually describe as character-building, I decided to make biochemistry my medical speciality. However, my boss was entirely uninterested in his ‘trainees’. It became clear that I’d made a mistake. To give myself something to do, I invented a research interest.

I got interested in the theory of analytical errors (instrument calibration was a big part of automated clinical chemistry), and gradually realized that there was a gap in the literature. I set out to fill this, using what resources I had: pen and paper, a systematic habit of mind and A-Level maths. Searching the literature was a very physical business of card index and bound journals. I’d been well-trained in this as a student, but it had never occurred to me that I might write papers as well as read them (my teachers had included eminent researchers, but I had evidently seen an unbridgeable gap).

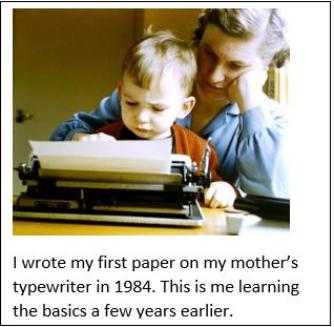

In my rather odd situation there was no-one to give me academic advice. I certainly didn’t tell my boss. Eventually I had a manuscript (literally: ‘a document written by hand’), and I resolved to submit it to Clinical Chemistry, the top journal in the field. But how? My mother was a shorthand typist, so I borrowed her old portable and laboriously pecked out a typescript.

The paper was heavily mathematical, and I had to do the superscripts and subscripts by cutting tiny letters out and sticking them on the page, smoothing their outlines with Tipp-Ex so they didn’t cast shadows in the photocopier. I posted it off with feelings I can no longer recall (although it’s not difficult to imagine). Amazingly, it was accepted.

What was the most significant thing for you about the paper?

It describes a framework to classify the errors to which a simple (and therefore easily automatable) calibration method is vulnerable, and suggests some ways to reduce them. There are several reasons I’m fond of it. It was absolutely 100% my own. It still reads well. Abstract points made with simple mathematics can’t become obsolete, even if they become uninteresting. It’s still being read, or at least cited: Google Scholar finds 152 citations, mainly in patents (I may have missed a trick there), and once in a standard textbook.

Lastly, it started my real career: it helped me get a ‘Research Registrar’ post (no real modern equivalent) in university clinical biochemistry; that led to a clinical research fellow post in an MRC unit doing magnetic resonance imaging/spectroscopy; then I came to do similar work as a Senior Registrar in Liverpool, where I’ve been ever since. The support of local NHS clinical biochemistry management enabled me to reconnect with my medical specialty (which I’d recklessly neglected during my move into research), so although I’ve had the opposite of a modern Integrated Academic Clinical Training, it’s more or less worked out.

What advice would you give to others about submitting their first paper?

That a poorly-structured job and a terrible boss can be useful motivation? True, but you learn in Head-of-Department Training that this is not a useful management tool. That you should work in secret and let no-one even read your drafts? That’s recognized to be suboptimal. That sheer chance is a powerful force? True, but unhelpful as careers advice. The positive lessons, I think, are genuine but platitudinous. I’ll limit myself to one: you can (quite possibly) do this!