The ‘story’ is an important instrument in qualitative research about long term conditions.

Nicci Gerrard, whom I know from the community of people advocating for people with dementia and their carers, wrote a beautiful review of Dr Rachel Clarke’s book, “Dear life” in The Guardian, I thought.

“Clarke is writing about dying, but also, eloquently, about living. In Clarke’s hospice, on good days, she sees her patients living as they approach their ends, freshly aware of life’s everyday loveliness. And the passages in her book that made me want to weep were not the ones about dying, but the ones about living, loving, learning how to say goodbye.”

There’s nothing more human than dying or death, and both topics which have fascinated me recently. These topics will at some stage touch everyone in their lifetimes. I recently had the privilege of looking after my mum with a progressive physical frailty and dementia syndrome until her death in July 2022.

My undergraduate and postgraduate training in medicine had barely prepared me for this role of unpaid family carer. The academic space of death and dying, outside the direct domain of medical end-of-life care, is diverse and healthy, including anthropological approaches to loss in other jurisdictions such as Japan, or existential sociology.

Unsurprisingly, I had begun to look for other sources of inspiration. Since my mum died in July 2022, I’ve been meaning to write a non-fiction book based on my lived experience of being an unpaid family carer. Writing various medical books was easy in comparison.

Caring for my mum made me realise how little I understood disability. Disability is very personal to me too, having had meningitis in my early 30s. I feel that disability is poorly understood by both the legal and medical professions. It is a personal phenomenon for many millions.

Frida Kahlo was an iconic world-famous Mexican artist, known also for her Surrealist art. Her disability began with being born with spina bifida. She then developed childhood polio at the age of six, and, at eighteen, she was in a bus accident, leaving her with a serious of injuries. While recovering from her injuries, Frida started painting, focusing on self- portraits, many of her paintings reflect her perception of her own disability.

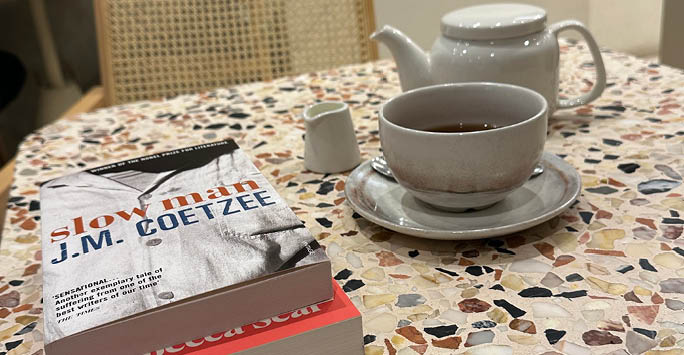

The book, “Slow Man” by J. M. Coetzee begins abruptly with 60-year-old cyclist Paul Rayment being hit by a car on McGill Road, thrown through the air and subsequently badly injured. When he wakes up in a hospital, he is told that his right leg must be amputated... and so the book continues. This fictional account reminded me of my own real life, how I suddenly became physically disabled from meningitis in the summer of 2007, waking up on the top floor of a North London hospital having spent two months in a coma.

In pursuit of understanding lifelong ageing in a more holistic way, I have been more tuned into the medical humanities. This week, the doctor and author Dr Rachel Clarke presented an Arvon Masterclass two hour workshop on how to write non-fiction. I’ve always wanted to write a book on my experience as a carer for my mum; that’s why I went to Rachel’s workshop.

I wrote down what Rachel said at the beginning because her words were so powerful:

“You want to share your experiences with a wider audience. What I want to suggest to you is, the following: whatever job it is you do, there is something unique that you bring to your workforce that is valuable, and unique to you. The way in which we interact with the world is uniquely yours. I know this as a doctor and as a writer. It doesn’t matter what somebody 'does'. No human is 'boring'. That’s just impossible. You are a unique human being. Your challenge is to describe your story in a way that entices the public.”

Rachel immediately made a link between the power of writing and social justice. Absolutely coincidentally, I read last week a brilliant paper in the Sociological Review from Lynch and colleagues which profoundly moved me. That paper introduced Nancy Fraser's work which has been much discussed by various philosophers, political theorists, and sociologists in relation to 'social justice'. Grounded in a view that equality and social justice are problems of parity of participation, Fraser outlines three key conditions that are required for the principle of participatory parity to be upheld.

Around Christmas last year, I was invited to be an Honorary Visiting Professor in the School of Law and Social Justice at the University of Liverpool. In fact, social justice has run through my adult life like letters of ‘BRIGHTON’ in a stick of rock. I did my Masters of Law in 2010, but I learnt little about social justice through my formal studies. How the law deals with moral issues and matters of social policy is a complicated, and inadequate, subject.

I first became aware of this discussion around 2009 when I attended a talk by the late Lord Justice John Laws. He was talking about how human rights can be approached entirely legalistically. We then discussed how lawyers make decisions reflecting justice for disabled appellants. I only became disabled as an adult when I suddenly contracted meningitis in June 2007. This personal biographical disruption in my life brought into sharp focus the added discrimination and prejudice I faced by being physically disabled, on top of being British Bangladeshi.

Rachel’s main thesis was, however, that writing was important to rail against social injustices.

Actually, this made complete intuitive sense to me. I’ve been thinking about what sort of genre might suit me best, including the memoir. One of the messages which Stephen King gives about the process of writing is essentially ‘read more’. Towards the end of last year, I read substantial parts of the memoirs of Barack Obama, Martin Amis, and Hilary Mantel.

At the last main count, there were five million individuals in England and Wales doing an ‘unpaid caring role’, and basically looked after their loved ones because there’s no-one else around to help or care is unaffordable. They often give up a salaried job of their own. They basically keep the whole health and social care system afloat. The situation is at crisis point. These five million people are filling in the gaps in a system at crisis point.

How can you write about any of this without getting angry? Rachel’s workshop was a revelation to me on how we can all use non-fiction to campaign on issues of social justice. Rachel addressed how to write feeling angry:

“This anger in this maybe ugly form may not end up in this form in the final form. But I need to get the words out. It needs to be edited later. I will bash out words ‘til 3 in the morning. If you feel anger, use it. This applies to anger, grief, any emotion.”

Writing a book of non-fiction will be one of the hardest things I’ve ever done. But the mere act of preparing for this exercise in itself has taught me lots. Clinical care is complex enough anyway, but there’s lots to learn about medicine from the humanities including sociology and English literature. I felt I had become super-saturated in the medicine of ageing, but that end is just the beginning.

Dr Shibley Rahman joins the University of Liverpool as a Honorary Visiting Professor associated with the Centre for Ageing and the Life Course.