Shaëny Cassim-Itibar talks about her experiences at the recent event 'Ethics for Social Justice Research: Learning from Creative Approaches' event held in June 2025 at the University of Liverpool.

Ethics is always a sensitive topic. So, when we set out to organise an event focused entirely on ethical research, we knew it would come with hesitations, preconceptions, and plenty of frustration.

For those of us who’ve gone through the institutional ethics approval process, it often feels like a rite of passage: a confusing, exhausting, and sometimes isolating experience. We thus share kinship through endurance. And for those who haven’t experienced it, they can only empathise. But strangely, what I felt during the Ethics for Social Justice Research: Learning from Creative Approaches event held in June at the University of Liverpool isn’t frustration but hope. This was a space where creative approaches met critical reflection, where ethics was not reduced to procedures and forms, but reimagined as something that could be meaningful, community-led and deeply human.

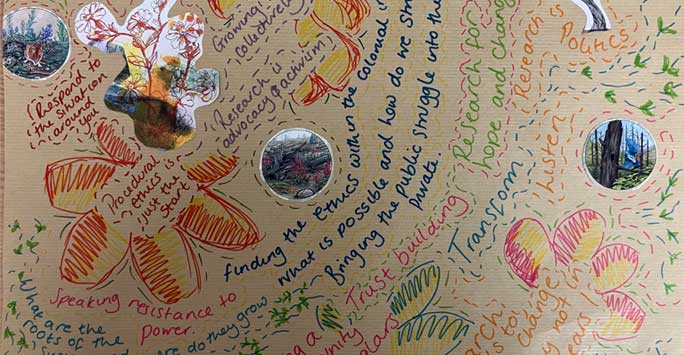

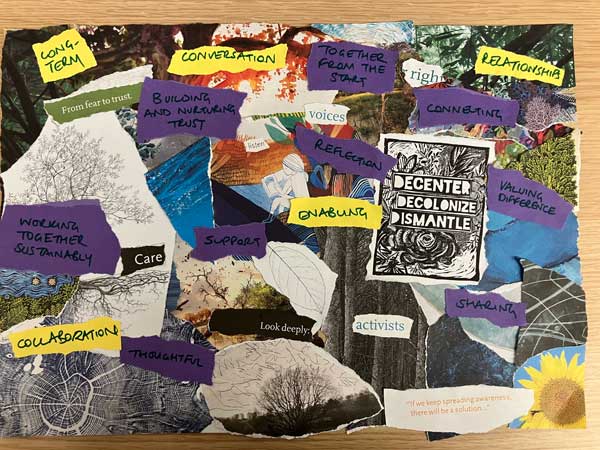

We began with something unexpected: stillness. Dr. Tegan Brierley-Sollis opened the day with a 15-minute mindfulness meditation, setting a reflective and grounding tone. Artists from More than Minutes captured seven hours of conversation in real-time visual storytelling. Local flowers adorned each table. We were invited to create collages, respond to prompts, and reflect individually and collectively on what ethics means for us. What might sound playful or even “childish” quickly revealed its power. Academics (even members of the ethics committee!), activists, and community members became co-conspirators in a shared reflection.

At my table, colleagues began by expressing frustration, writing out how they felt institutional ethics processes had obstructed their work, imposed arbitrary restrictions, or undermined participatory approaches. But the more they wrote and cut pieces from magazines, the more their definitions of ethical research grew more hopeful, centred around mutual respect, accountability and care.

I also had the opportunity to share my own story. In my experience, some aspects of the ethics process created challenges for the way I had originally hoped to conduct my PhD research. The concerns raised by my committee often felt more like box-ticking than genuine ethical reflection. I had planned to run weekly food-based sessions with my participants. They were Nigerian survivors of sex trafficking who had been displaced to the Southeast region of Senegal. Each week, a new group of three to five women would join a session where we would collaboratively choose a recipe, cook, eat, and talk about their perceptions and expectations of justice.

I also had the opportunity to share my own story. In my experience, some aspects of the ethics process created challenges for the way I had originally hoped to conduct my PhD research. The concerns raised by my committee often felt more like box-ticking than genuine ethical reflection. I had planned to run weekly food-based sessions with my participants. They were Nigerian survivors of sex trafficking who had been displaced to the Southeast region of Senegal. Each week, a new group of three to five women would join a session where we would collaboratively choose a recipe, cook, eat, and talk about their perceptions and expectations of justice.

I had chosen this method precisely because it was culturally grounded and had the potential to create a familiar, safe environment for my participants. In the end, I wasn’t able to fully implement this method because of the additional time the ethics review required. But we still cooked and ate together informally. And honestly? Those moments held more meaning than any recorded interview. What does this say about our current ethics systems? That there can sometimes be a gap between formal ethical procedures and the ways researchers and participants actually navigate ethics in practice. Institutional ethics understandably emphasises consistency and risk management, but in doing so, it may not always capture the relational, human dimensions of research.

Defining ethics

Those different questions and approaches were echoed throughout the day. Community members challenged the idea that “ethics” should only be defined by academics or those in power. As Emma Rogan from Investing in Children put it: “Just because it’s uncomfortable doesn’t mean it’s unethical.” Her work with children highlighted the contrast between rigid academic frameworks and the more responsive, inclusive ethics found in community work. And yet, institutions continue to co-opt the very language that emerges from the margins. Akil and Seth Scafe-Smith (2025) recently warned about how British institutions have appropriated the language originally used by marginalised communities to denounce harm...only to depoliticise it. Terms like “co-production,” “lived experience,” or “participatory” are now routinely used in institutional rhetoric, often stripped of actual commitment to change (Scafe-Smith & Scafe-Smith, 2025: 10).

Professor Phil Scraton also warned that the word “co-production” invading academic discourses is at risk of being manipulated. We must ask whether we are genuinely working with communities or simply using their language while continuing to design processes that exclude and disempower them. Especially in research framed as advancing “social justice,” the irony of reproducing the very harms we claim to resist should not be lost on us.

This wasn’t just about semantics. It raised deeper, urgent questions: How can institutions claim to care about ethical research while remaining silent or even complicit in the face of a genocide and global injustices? Why are conversations about ethics so often led by those furthest from the communities their decisions affect?

These critiques didn’t overshadow the event – they strengthened it. They revealed that institutions have long failed to listen. But they also showed what’s possible when spaces are created for honest, creative, and collective reflection. This event showed that moving away from formal, anxiety-inducing structures can unlock deeper conversations and real, actionable change. It brought the community and the arts inside the institution, not as decoration but as central to reimagining what ethics could look like.

Making ethics inclusive

Image: Collage produced by Liz Stewart, Museum of Liverpool.

Of course, we shouldn’t shower ourselves with praise too quickly. The push for better, more inclusive ethics is long overdue. Marginalised and Indigenous communities have been practising respectful ethics for generations. We see this ethic in Aotearoa (New Zealand), where Māori communities uphold the values of whānau (family/community) and manaakitanga (care, respect, generosity and hospitality) through marae gatherings. These communal spaces are living ethical frameworks, where care and decision-making are practised through shared meals, storytelling and rituals (E Tū Whānau! 2025).

We also see it right here in Liverpool. In L8, the fight for racial justice led to the 1981 uprisings, but it also gave rise to decades of community organising grounded in mutual care and resistance. Creative spaces like the Kuumba Imani Millennium Centre continue to offer support and uphold social justice for the local community. BlackFest, a grassroots festival founded in 2018, uses different creative approaches such as music, poetry and film, to celebrate Black artistry and to open space for dialogue, representation, and healing.

And that’s the real takeaway for me. When we continue to ask how we can improve ethical research, we must remember that we’re late to the party. But we can still show up. We can build spaces that honour creativity, collective knowledge, and community voices. This event proved that.

There is hope.

References

BlackFest (2025) About us - Blackfest

E Tū Whānau! Te Mana Kaha o te Whanau (2025) Maori-Values-A4-x-9-sheets.pdf ETW_ManaManaaki-WEB.pdf

Kuumba Imani millenium centre (2025) Kuumba Imani

Scafe-Smith.A., and Scafe-Smith.S. (2025) ‘Speak of the devil: Reflections on the institutional co-optation of language’ in The Funambulist: Return, n°58.

Image credits

With thanks to Liz Stewart and Gemma Bird whose collages feature found materials including fragments of work published in Resurgence and Ecologist. Relevant fragments/source images have been reproduced here with kind permission of Jana Nicole (https://jananicole.com/); Ethan Murrow (@murrowethan); Marian F. Moratinos (https://www.marianfmoratinos.com/).

We have endeavoured to identify any large portions of works reproduced here and seek permissions to use these. If you believe an element of your work has been reproduced here without permission and you would like to raise this, please get in touch by emailing: w.asquith@liverpool.ac.uk