Emily Kearon-Warrilow reflects on her experiences at the recent event 'Ethics for Social Justice Research: Learning from Creative Approaches' event held in June 2025 at the University of Liverpool.

Historical research demands ethical consideration. Yet, as we Historians (for the most part) work with the dead, we are typically not required by our institutions to participate in formal ethics processes. I was, therefore, thrilled to work with colleagues from the Politics and Law departments to organise and participate in the Ethics in Social Justice Research workshop in June 2025.

The workshop, led by Dr Wendy Asquith, used innovative and creative methods to open up a space for challenging conversations about research ethics among academics, frontline social justice practitioners, research participants and ethics staff. As an Historian of sexual violence in Britain and its empire, I am constantly engaging with questions of research ethics in my own work. I was, therefore, keen to see what these conversations could bring to my own discipline and entered into these discussions with eyes wide open; with few preconceptions and much to learn.

What should ethical research look like?

Curiosity and openness were encouraged from the offset by Tegan Brierley-Solis, who began the event with a guided mediation. Having set the tone for a collaborative environment, the event moved on to provocations from critical criminologist Professor Phil Scraton, PhD student Shaëny Cassim-Itibar, and lecturer and Chair of the Research Ethics Committee Dr Ed Horowicz.

Professor Scraton’s galvanising speech encouraged the group to interrogate what ethical research should look like, while his call for closer alliances between academics and activists embodied the vision of the newly established Centre for People’s Justice. This electric critique of institutional research ethics processes was followed by Shaëny Cassim-Itibar’s poignant account of her own research, in which she shared how the preference of ethics committees for conventional research methods can result in the value of more creative methods being overlooked, despite these often being more attuned to benefits for participants and their welfare.

These are precisely the kinds of conversations researchers and ethics committees should be having, according to Dr Horowicz, who reminded us of the importance of the ethics process for quality research. What followed was a series of informal discussions and panels in which participants mused on the ethics of social justice research.

When it comes to ethics committees, one activist asked, do we ever consider the ethical implications of saying ‘no’ to doing research? What does it mean to not do the research, and is such a decision always the lesser of two evils? Such a question harked back to Dr Horowicz’s contention that the ethics process should not necessarily shut down research but should instead encourage a dialogue between ethics staff and researchers, to enable researchers to think more deeply about their projects. Rather, the ethics process should be a tool for researchers as, to quote Dr Horowicz, ‘good research is ethical research’.

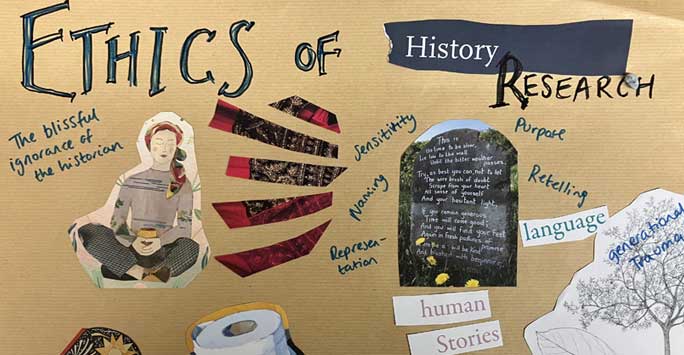

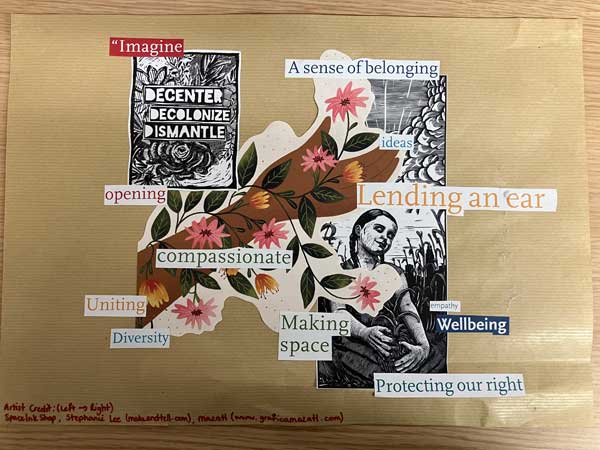

A collage created by Dr Bethany Jackson, Nottingham Research Fellow, School of Geography at the University of Nottingham.

Ethical research for historians

While such deep thinking is, of course, encouraged in History, there is no formal process to ensure Historians are critically engaging with such questions. This is not to say that all historical research should go through formal ethical approval, as certain topics require considerably less engagement with research ethics than others.

Yet, since many of my research subjects are children and/or colonised peoples – many of whom were subject to violence – I have had to think carefully as to how to tell these histories and why they should be told. I have come across countless harrowing stories in the archives, yet we historians must take care to not merely reproduce these tales for dramatic effect. The point is not to shock, or to muse on how ‘bad’ things ‘were’; the value of a story is not in the gruesome details.

The purpose of retelling the story of a sexual assault on a working-class girl in 1880s Britain, for example, could be to highlight class inequities in legal protection, and to provoke conversations about the legacies of this in the present. What historians do with such stories, and how we tell them, matters – both for the quality of historical research and for social justice.

Historical research is a social justice endeavour. While historians deal (mostly) with the dead, it is the contention of our discipline that the lives of our subjects held meaning. As Professor Lydia Hayes pointed out, while an ethical approach is crucial in any research, social justice research should be leading the way and helping to inform on how to do truly ethical work.

What was clear to me, as someone somewhat on the outside looking in, was that historians could benefit immensely from more engagement with questions of research ethics. An imperfect tool is a tool, nonetheless. For those of us historians who must consider difficult ethical questions in our own research, using such tools will only help us to produce better, more meaningful work.

Image credits

With thanks to workshop participants including Bethany Jackson whose collages feature in this post. These contain found materials including fragments of work published in Resurgence and Ecologist. Relevant fragments/source images have been reproduced here with kind permission of Rachel Grant Art (http://site.rachel-grant.com/home.html); Rithika Merchant (https://www.rithikamerchant.com/) and Stephanie Lee (http://makeandtell.com). We have endeavoured to identify any large portions of works reproduced here and seek permissions to use these. If you believe an element of your work has been reproduced here without permission and you would like to raise this, please get in touch by emailing: w.asquith@liverpool.ac.uk