In June 2025, researchers, practitioners, and community partners gathered at the University of Liverpool for a dynamic workshop on ethics in social justice research. In this blog, research assistant Adam Burns talks about his experiences of the day.

Hosted by Dr Wendy Asquith, in collaboration with the new Centre for People’s Justice, the event provided an inspirational space to rethink the relationship between formal research ethics approval and ethical research practice, and to imagine what truly ethical, impactful research might look like.

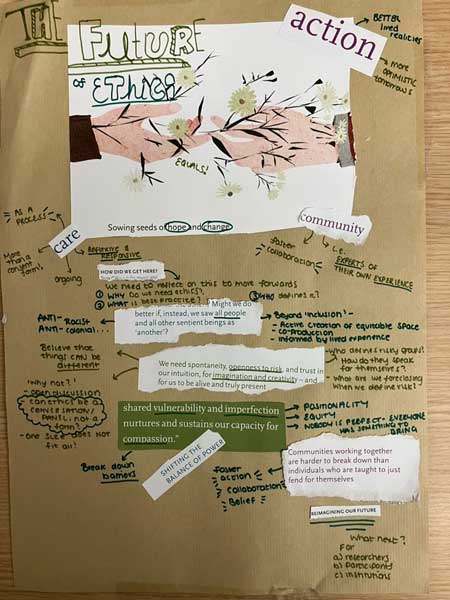

Collage created by Katie Douthwaite, Postgraduate Researcher, Keele University.

As a research assistant on a Modern Slavery and Human Rights PEC-funded project and a prospective PhD student exploring anti-trafficking interventions, these conversations struck a deep chord.

We presented findings from our Modern Slavery PEC funded project, which focuses on evaluating the ethical dimensions of research into modern slavery. Our research particularly centres on the challenges that institutional systems and structures can pose to co-producing work with lived experience experts.

In partnership with colleagues at Traumascapes, we’ve taken a novel approach to this by undertaking work to translate the findings of our team’s report on Ethics in modern slavery research into accessible, creative outputs: an animation, an infographic, and a visual guide. These seek to equip researchers, funders, and participants with practical tools for building ethical, co-productive research relationships. At the heart of this work is a belief that ethics should be collaborative and ongoing, not simply an institutional hurdle to clear, but a shared framework for accountability, inclusion, and justice.

Ethics as collaboration

That spirit of collaboration was very much alive throughout the Ethics for Social Justice Research workshop. Structured around guided creative exercises, provocations, and open discussion, the day invited participants to reflect critically and creatively on the ethical challenges they face in their work.

To begin, a free writing task and reflective meditation encouraged openness, prompting reflections on accountability, structural inequality, and the ethics of choice. Rather than a rigid code, ethics was positioned as a living process: one that should enable meaningful research rather than restrict it.

This theme continued through a series of thoughtful provocations by Professor Phil Scraton, Shaëny Cassim-Itibar, and Dr Ed Horowicz. Professor Scraton’s address grounded ethical research in wider structural realities, asking us to consider how we transform “personal troubles” into public critique and, ultimately, socio-legal change. He warned against professional discourses that sanitise complexity and instead called for an “oppositional view from below” - research that resists dominant regimes of truth and actively listens, carefully, to marginalised voices.

Shaëny Cassim-Itibar shared lessons from her own participatory research practice in Senegal, highlighting how the ethics process can often sideline creative or community-based approaches. Her account of seeking to use shared cooking as a research method revealed the value of non-traditional, embodied ways of building trust. She also raised key questions about the benefit to participants: who really gains from research, and how do we account for intangible forms of value like solidarity?

Dr Horowicz, who chairs the university’s ethics committee, acknowledged the bureaucratic challenges of the current system. He reflected on the disjuncture between submitting a proposal and conducting meaningful research in the real world, where trauma, risk, and trust can’t always be neatly pre-empted. Rather than policing from above, he called for ethics as dialogue, a co-produced, human-centred process that prioritises the well-being of both participants and researchers.

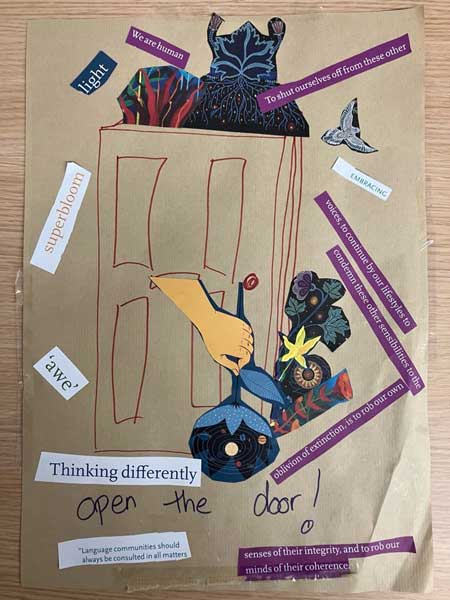

Collage created by a participant at the Ethics for Social Justice research workshop

Insights through creativity

In breakout discussions, participants used collaging, creatively echoing these themes, sharing frustrations about institutional gatekeeping and the limits of formal processes. Practitioners from community organisations, such as Emma Rogan from Investing in Children spoke of the need for flexibility, responsiveness, and trust, values often absent in bureaucratic academic frameworks. Diane Garrison from Liverpool John Moores University also raised key questions of how ethical relationships can be sustained when funding ends or institutional support falls away.

What emerged clearly was that ethics isn’t something we do before we begin; it’s something we live throughout the research process. The institutional ethical approval process is just one part of a much bigger picture, one that includes emotion, accountability, and the unpredictable reality of fieldwork.

Research in and for social justice must always ask hard questions - not only of the systems we study, but of ourselves. That process doesn’t stop with approval. It begins there.

Image credits

With thanks to workshop participants including Katie Douthwaite whose collages feature in this post. These contain found materials including fragments of work published in Resurgence and Ecologist. Relevant fragments/source images have been reproduced here with kind permission of Xuan loc Xuan (https://www.instagram.com/xuanlocxuan); Christi Belcourt (http://christibelcourt.com/) and David Abram’s The Spell of the Sensuous (https://www.davidabram.org/). We have endeavoured to identify any large portions of works reproduced here and seek permissions to use these. If you believe an element of your work has been reproduced here without permission and you would like to raise this, please get in touch by emailing: w.asquith@liverpool.ac.uk