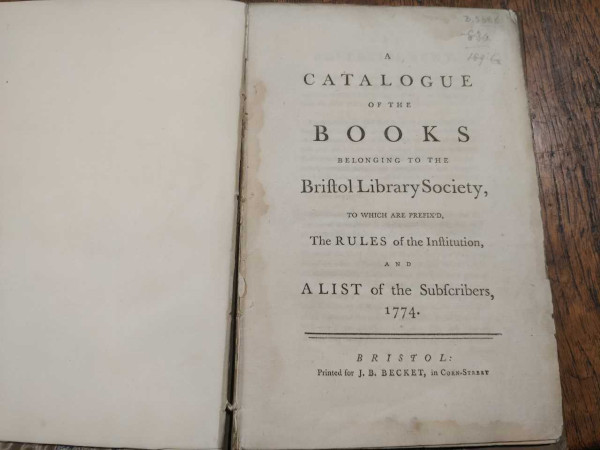

The toppling of the statue of the slave trader Edward Colston (1636-1721) in Bristol on 7 June 2020 has reminded a whole country – and many other parts of the world – of the city’s historical involvement in the slave trade. In the eighteenth century, Bristol prided itself as the second city of the British Empire and the traffic in human beings played a seminal role in creating the city’s wealth. In the second half of the century, the city used its increased prosperity to found cultural institutions, and one of the most notable ones was the Bristol Library Society, established in 1772-73. As a postdoctoral member of Professor Mark Towsey’s AHRC project on ‘Libraries, Reading Communities and Cultural Formation in the Eighteenth-Century Atlantic’, I conduct research on this institution and recently signed a contract with Bristol Record Society to publish an edition of its eighteenth-century committee minutes in book form.

Many slave traders were prominent members of the Bristol Library Society. James Tobin, for instance, who served on the library’s committee in the late 1790s, was a sugar planter and a pro-slavery campaigner with business interests in Nevis. Thomas Daniel Junior, born in Barbados, had a stake in several slave plantations and applied for compensation in 1834. The fortunes of the Ames and Elton families, both represented in the library’s membership, were firmly rooted in the slave trade. The list goes on.

There were also several members of the library who were engaged in the abolitionist movement. Joseph Harford, one of the library’s founders and member of one of the city’s prominent Quaker families – although he converted to Anglicanism – became chairman of the first local abolitionist committee in Bristol in 1788. His fellow Quaker Richard Champion, also a founding member of the library, condemned the institution of slavery in writing in 1787. However, it is clear from his correspondence in the 1760s and 1770s that Champion had earlier condoned the slave trade in private and as a merchant he is likely to have been implicated in the traffic.

One of the library members who wrote against the slave trade was the Anglican clergyman Francis Randolph. In opposition to the aforementioned Tobin, Randolph wrote in A Letter to William Pitt on the Proposed Abolition of the African Slave Trade (London, 1788) that Britain, as ‘an enlightened and a Christian Nation’, had no right ‘to exercise this inhuman Branch of Traffic’. In a Christian-utilitarian argument, Randolph argued that the prosperity meant that the British had a duty to ‘increase the general Sum of human Happiness’. Many of the anti-abolitionists argued that enslaved people were better off in their new habitat than in Africa. According to Randolph, even if this had been true, this could not justify the purchase of human beings. Drawing on his reading of Montesquieu – one of the most frequently borrowed authors at the library – Randolph argued that human nature can vary but not differ. All human beings had the same mental potential and the same capacity for virtue. As he wrote: ‘if we were forced to seek for the Virtues or the Dignity of the human Race onboard an African Trader, it would be amidst those who were groaning under their Misery; not among those whose Vice and Brutality could inflict it.’ This is reminiscent of Adam Smith who had written in The Theory of Moral Sentiments (1759), one of the library’s early acquisitions:

'There is not a negro from the coast of Africa who does not…possess a degree of magnanimity which the soul of his sordid master is too often scarce capable of conceiving. Fortune never exerted more cruelly her empire over mankind, than when she subjected those nations of heroes to the refuse of the jails of Europe, to wretches who possess the virtues neither of the countries which they come from, nor of those which they go to, and whose levity, brutality, and baseness, so justly expose them to the contempt of the vanquished.'

Randolph stopped short of calling for the immediate abolition of the slave trade. Instead, he wanted to see it phased out. He held this gradualist approach in common with Edmund Burke, who had also argued for the phasing out of the slave trade in Sketch of the Negro Code in 1780. Like Smith (and William Wilberforce), Burke believed that the British were connected to the Africans because of ties of sympathy between all human beings. This has been highlighted in a recent book by P. J. Marshall entitled Edmund Burke and the British Empire in the West Indies (Oxford, 2019). Marshall’s important book also sheds new light on Burke’s lesser known and more dubious activities in support of the Company of Merchants Trading to Africa during the period between 1774 and 1780, when Burke represented Bristol in parliament. At this time, Burke also became a member for life of the Bristol Library Society.

,(1).jpg)

As this short blog post has shown, even if very few emerge from this episode with an unblemished record, theoretical arguments against slavery and the slave trade can be found in Enlightenment literature, along with many unequivocally racist and imperialist statements and arguments. The Bristol Library Society, like most Bristolian and many British institutions at the time, was supported by money from the slave trade, but it also helped circulate ideas that inspired some people to campaign against it and help bring about its downfall. This is of course only a part of the story, and it does not incorporate the way in which enslaved people fought for their own liberation. Even though the British slave trade was abolished in 1807, the abolitionist movement did not eliminate the legacies of British slavery. On 7 June 2020, this was reflected in the anger directed against the Colston statue, erected nearly two centuries after he died in 1895.

Discover more

Study in the Department of History at the University of Liverpool.

We understand that this is a worrying and uncertain time for everyone, and the wellbeing of our students is our highest priority.

The University is here to offer you support and guidance as you continue with your studies. Please check your University email account daily so that you can continue to access advice and support from your module tutors regarding the shift to online teaching and alternative assessments.

The School will communicate with you regularly in response to students’ key concerns. Information is also available on our Coronavirus advice and guidance pages.

However, if you are have a specific query that you are unable to find the answer to online, please contact either your Academic Advisor or the Student Support Centre at hlcenq@liverpool.ac.uk