6 February 2018 marks a centenary of the extension of suffrage to some women (and men). Women over 30 who owned property or were graduates voting in a university constituency, around 8.5 million women, were able to vote after the 1918 Representation of the People Act.

Universal suffrage was gained 10 years later in 1928. Celebrating 2018 as the centenary of suffrage must serve as a reminder of the importance of inclusivity and to be mindful of those women we leave behind.

With this in mind, we asked our students what suffrage means to them…

If we sometimes forget the historical significance of having the right and ability to vote, pictures of those who have not always had that privilege queuing in long lines down a road, sometimes at great personal risk, to cast their first ballot can act as a poignant reminder. Considering the twists and turns of history, of struggles for power, of oppression, that we can hold those who govern us to account by simply ticking a box is quite remarkable. As women, it is impossible to not feel this even more acutely, knowing the individual sacrifices and considerable determination that finally turned "Votes for Women" from a campaign slogan to a basic principle of our democracy.

Alexandra Woods, Politics PhD researcher

My first vote was in 2005, I have exercised that right in 4 General Elections and 1 referendum so far and I am yet to see a successful result. I was ten years old in 1997 when Labour won the General Election and I can remember the elation in the atmosphere of my community. Reflecting back, this represents a time when I became aware of societal injustice and class inequalities, but most importantly, the power of voting. Being able to vote is about inclusion; inclusion in a process that is complex, frustrating and so far, unrewarding. Yet, rather than being resentful about the negative components, I respect the privilege of being able to vote and appreciate that being a part of the process is the only way to see results.

Michelle Holding, Politics undergraduate

I think the Representation of the People Act was a valuable step forward towards gender equality for political rights. I think it is important to remember it, however, insofar as it raises the debate around feminism and about how gender equality and democratic participation are so much more than just the right to vote.

Stephanie McDonagh, Politics undergraduate

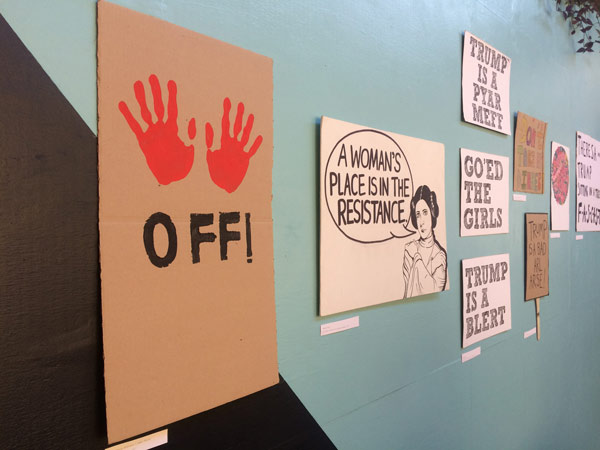

Exhibition of protest art at Constellations in Liverpool

Listening to the women who are de facto left out of suffrage may not be thought of as prominent, compared to women who are excluded through law. A women choosing not to exercise her right to vote is a choice at least. But rather than taking a face-value answer of political disengagement, and sweeping it under the monolithic conception of women one can look further. Women's suffrage within male constructed institutions highlights an important point how these institutions work for women. Is the translation of a women's whole political experience into a vote enough? This is true for men too, but as women continuously transgress the private-public spheres, a woman's personal political experience may not be resolved through suffrage: women's dominance of informal economies, violence received from men, and gendered experiences of class. When looking at who is excluded from suffrage, taking a deeper look at women who are not exercising their right and why, may help us understand why existing political institutions were not necessarily built for the women, and why other political activity beyond parliamentary channels may benefit them more.

Heather MacDonald, Politics undergraduate

The celebration of hard-won human rights is important, but what feels more important is the continued pursuit of universal human rights. Although celebrating this milestone is important, it is crucial to note that the right to vote is not universal: For many groups, the right to vote is not given, nor is it prioritised as an issue in need of correction by governments. All prisoners, regardless of the severity of their crime, lose the right to vote. Victims of domestic violence (often women) who live in refuges lack a permanent residence necessary to register. The exclusion of prisoners seems to have no link to the goals of the criminal justice system; it is neither preventative nor reintegrative to remove a basic human right. What is especially unfair about this law is prisoners, or domestic violence survivors, are often the people most affected by cuts and other socioeconomic policies. To exclude a group of people potentially most affected by the outcome of the vote seems far from the flourishing democracy you would picture in a country which has had universal voting for a century.

Beatrice Lee, Politics undergraduate