Led by a medical educator, the initiative used ChatGPT to produce realistic depictions of conditions like jaundice, eczema, and cyanosis across a range of skin tones and body types to ensure future doctors can accurately diagnose all patient populations. By integrating these expert-vetted, synthetic images into the curriculum, the project aims to build student diagnostic confidence and reduce health disparities caused by misdiagnosis in patients of colour. Read on to discover how this innovative "stop-gap" measure is fostering a more equitable visual curriculum and preparing graduates for a multicultural healthcare environment.

Please briefly describe the activity undertaken for the case study

Background: Medical educators have long noted a glaring underrepresentation of Black, Asian, and Minority Ethnic (BAME) individuals in clinical images used for teaching. Studies have found that only about 4–5% of images in major medical textbooks depict dark skin tones (Adelekun et al., 2018). This lack of diversity of gender and skin tones is not just an issue of representation; it has tangible clinical consequences. Conditions such as rashes, infections, and dermatological diseases often appear differently on darker skin, and without diverse reference images, healthcare professionals can miss or misidentify these conditions. Indeed, general practitioners have been shown to misdiagnose melanoma on Black skin at far higher rates than on white skin – in one study, two-thirds of diagnoses on Black skin were incorrect, compared to under 15% on white skin (Lyman et al., 2017). Such disparities contribute to delayed treatment and worse outcomes (for instance, five-year melanoma survival is around 70% for Black patients versus 92% for white patients in the US (de Vere et al., 2023).

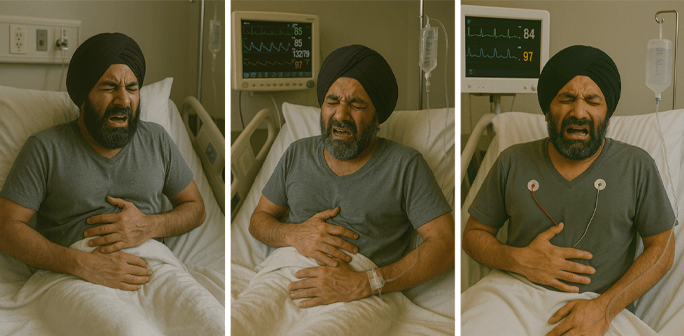

Activity Overview: To address this, I led an innovative project leveraging ChatGPT’s image-generation capability to create clinical images with more diverse skin tones and body types. The activity involved using an AI tool (integrated with ChatGPT) to generate realistic images of various medical conditions as they appear on patients from BAME backgrounds. By prompting the AI to produce images (e.g. “a photograph of [medical condition] on a range of skin tones” or “on a woman of colour skin”), the team built a collection of illustrative clinical images featuring a wide range of skin tones and body types. The aim was to enrich teaching materials with these synthetic yet authentic-looking images, thereby creating a more inclusive visual curriculum. In essence, the project’s aim was to use generative AI to fill gaps in traditional image databases and to ensure students see beyond the narrow scope of “textbook” patients; ideally, medical texts would feature more varied patient examples, and this project is not intended to be a long-term replacement for images of real people, but rather a stop-gap measure to ensure our students receive the education they need to improve patient outcomes, and also as a tool to raise awareness of this important deficit, prompting action to explore the recruitment of diverse patient images for traditional resources. The activity responds directly to the need for representation.

How was the activity implemented?

The implementation followed a structured yet exploratory approach, combining technology with pedagogical oversight:

- Identifying needs: I first pinpointed which clinical topics in the curriculum lacked diverse imagery. Dermatological conditions (e.g. eczema, psoriasis, chickenpox) and physical signs (e.g. jaundice, bruising) were obvious priorities, as these can manifest differently on darker skin. I also noted gaps in representation of different body types (such as images of procedures or examinations on patients of varying body sizes, ages, and genders).

- AI image generation: Using ChatGPT’s integrated image generator, the team crafted specific prompts to produce the needed images. For each scenario, multiple iterations were run. For example, to generate an image of jaundice on a dark-skinned patient, the prompt described the clinical setting and skin tone in detail. The AI then output candidate images. The same was done for other cases (e.g. a dermatology image of psoriasis on a Black patient’s torso, or an eczema rash on a South Asian woman). Body diversity was addressed by requesting variations (such as an overweight patient with condition X, or an older adult with darker skin showing symptom Y).

- Curation and verification: The generated images were carefully reviewed for realism and accuracy by specialists in the field of medicine that had been created for, such as Dermatology and Respiratory to verify that the images correctly illustrated the medical signs intended. Any AI outputs that were anatomically odd or clinically inaccurate were discarded. In some cases, the prompt was refined (for instance, adjusting the image of a patient's hand that had Rheumatoid Arthritis, as the hand was not aged enough to represent the cohort of patients Rheumatoid Arthritis will typically present in) to improve fidelity. This step was crucial to ensure that students would not be misled by AI artifacts.

- Integration into teaching: The final set of images will be incorporated into the pre session learning, the teaching sessions delivered and the students subject handbook that they are able to access independently to aid their subject knowledge. Some images that show a clinical condition on different skin tones will be used to explicitly highlights differences in appearance, whilst other images generated will be used independently to increase diversity in the images that are used within the department. The technology may also be used for assessment purposes to create images that students have never have access to before (via a generic internet search) to ensure that they are correctly identifying a clinical presentation.

- Ethical and technical considerations: No real patient data was used, so patient privacy was not a concern. Nonetheless, the team was mindful of ethical use of AI. The source of the images will be disclosed to students to maintain transparency and spark discussion about AI in medicine. While the use of generative AI to create diverse clinical images offers significant pedagogical and equity benefits, it also raises questions around cost and long-term sustainability. One advantage is that once a workflow and set of prompts are refined, image generation becomes relatively low-cost compared to commissioning professional illustrations or acquiring clinical photographs that require patient consent and logistics. Most generative AI platforms, including ChatGPT’s image tools, are accessible via subscription models that can be scaled institutionally. However, the process still demands human time—particularly for prompt iteration, expert validation, and integration into curriculum—which can be resource-intensive during initial implementation. Sustainability hinges on embedding these practices into routine content development cycles and potentially training academic and support staff to generate and vet images independently. From an environmental sustainability perspective, the energy usage of large AI models should be acknowledged, though the marginal carbon footprint per image is relatively low. Still, institutions using such tools at scale should remain aware of digital sustainability best practices and consider platform providers' environmental commitments when choosing AI services. Overall, the approach is cost-effective and scalable if managed with structured oversight and shared responsibility.

Throughout implementation, I collaborated with the Centre for Innovation in Education to align the process with best practices in digital education. The result was a curated repository of diverse clinical images that could be continually expanded or updated as needed. This repository will serve as a starting resource, with an ambition of the project to develop a bigger library of images for the Clinical Skills department at the University, ensuring that inclusivity is embedded in visual teaching content.

Caption: This is an example of Rheumatoid Arthritis that was generated. I sent the one of the left hands to the Rheumatology lead who said it was ok for early presentation, but it would usually manifest in the elderly. I adjusted my prompt to ChatGPT, and it generated the images on the right. Which are more common clinically.

Has this activity improved programme provision and student experience, if so, how?

Introducing AI-generated diverse images may have positive impacts on both the medical programme and the student learning experience. The images will be introduced to the curriculum from the next Academic year and evaluated accordingly. The impact that has been seen other studies:

- Enhanced learning outcomes: Students develop richer understanding of clinical presentations across different populations. By seeing conditions on a variety of skin tones, they learn to identify key signs (such as inflammation or cyanosis) even when those signs look subtler or different on darker skin. The images aim to directly address this known training gap – previously, many students felt less confident diagnosing skin conditions in patients of colour than in white patients. Now, with even a little more exposure to these images students are given the opportunity to build their diagnostic confidence in a more equitable way.

- Reducing misdiagnosis risk: The programme will better prepare future doctors to avoid the pitfalls that lack of representation can cause. Misdiagnoses due to skin tone differences can lead to life-threatening delays in care. By training with diverse images, students are more likely to correctly recognize illnesses in BAME patients

- Student engagement and inclusivity: The inclusion of diverse images makes the learning experience feel more inclusive and realistic. Representation can foster a sense of belonging and signal that the programme values diversity and equity in gender and skin tone. Overall, the activity has spurred meaningful conversations about health inequalities and cultural competence – with the aim of enriching the educational dialogue in the classroom and beyond.

- Programme innovation and reputation: From a programme provision standpoint, this initiative showcases the Clinical Skills department of the medical school as forward-thinking. It aligns with the university’s commitment to inclusivity and digital innovation. Utilising cutting-edge AI to solve a pedagogical problem demonstrates responsiveness to current issues and technologies. This not only improves the quality of materials (filling content gaps that existed in lectures and textbooks) but also prepares students for a future in which technology and medicine increasingly intersect. Informally, the case study has drawn interest from other faculty and even external educators, enhancing the programme’s reputation for educational innovation.

In summary, the activity aims to improve the curriculum by making it more comprehensive and inclusive. Students will be better equipped with the visual literacy needed for diagnosing a diverse patient population, which ultimately translates to improved clinical competence. The learning experience is more engaging and equitable, reflecting a curriculum that keeps pace with both societal needs and technological advancements.

Caption: This image was approved by our respiratory lead. You can clearly see how central Cyanosis may present differently on different skin tones.

Did you experience any challenges in implementation, if so, how did you overcome these?

Implementing this AI-driven activity did come with challenges, which the team addressed through careful strategy and support:

- Ensuring clinical accuracy: One of the foremost challenges was verifying that the AI-generated images accurately depicted the medical conditions. Early trials revealed that some images, while realistic immediately, had subtle inaccuracies (for instance, an AI-generated rash might lack the exact texture of a true eczema plaque, or an image of a lesion might exaggerate certain features). To overcome this, we established a verification step: each image was reviewed by medical experts before being approved for teaching use. In cases of doubt, the image was discarded or regenerated with a better prompt. This rigorous vetting ensured that no misleading images entered the curriculum.

- AI limitations and bias: Working with generative AI, we encountered occasional limitations. The AI model has inherent biases reflecting the data it was trained on – for example, if prompted generally for a “patient with skin condition X,” it might default to lighter skin unless instructed otherwise and a male patient appeared to be its default gender. We overcame this by being very explicit in our prompts about the desired skin tone and other demographic details. Another limitation was that the AI sometimes produced unrealistic outputs (extra fingers, distorted anatomy, etc.), which is a known quirk of image models. Through trial and error, we learned how to refine prompts and use selection: we would generate multiple images and choose the most accurate, rather than relying on a single output. Patience and iteration were key: for some conditions we ran many prompt variations until the result was satisfactory. We documented effective prompt phrasings as a guide for future image generation tasks.

- Ethical and acceptability concerns: Introducing AI-generated material raised some ethical questions and scepticism. Colleagues initially wondered if using “fake” images was appropriate for medical teaching, and whether it might confuse students. We addressed these concerns by transparently communicating the purpose and benefits. We emphasised that these images are a means to an end – to represent real clinical variation that existing resources lack – and that each image was vetted for accuracy. We will also brief students that the images are AI-generated, framing this as an opportunity to discuss how technology can aid learning (and even how AI might be used in diagnostics in their future careers). By treating the AI images as a validated educational tool, and not a gimmick, we hope to gain broad support. Additionally, since no real patient photos were used, we navigated around any patient consent or confidentiality issues that typically accompany clinical imagery. This reassurance helped ease ethical reservations.

- Technical and logistical challenges: The main challenge faced was being able to develop the images without being flagged as an inappropriate use of the technology. Because of the potentially graphic or explicit nature of the medical-related imagery requested, we would often be warned that the technology was being used in breach of its licence limitations. To counter this, prompts were refined to focus on an output that could be achieved. On the technical side, I invested time in understanding ChatGPT’s image generation interface and capabilities. The Centre for Innovation in Education provided support by connecting us with early adopters of such tools and sharing best practices. Over time, this technical learning curve flattened, and using the AI became a smooth part of the workflow.

- Time and volume: Initially, we were ambitious about generating images for every condition in the programme. We soon realized this was time-intensive – each image took multiple attempts and expert reviews. To manage this, we prioritised key areas (e.g. dermatology and clinical skills images) where impact would be greatest. We treated the project as iterative: a core set of images was developed for immediate use, and additional images are being created gradually. By phasing the work and possibly involving interested students or staff in the generation process as a project, we prevented overload and maintained quality.

In overcoming these challenges, a combination of collaboration, careful quality control, and iterative development proved crucial. The experience also yielded guidelines and knowledge that will make future AI-related initiatives easier – effectively turning challenges into learning opportunities for the team and paving the way for others to use this technology in their teaching practice.

Caption: This image shows the progression of the development of an image (starting from the left), I asked ChatGPT to add things to the image. However, despite multiple attempts, on the final image I could not move the cardiac monitoring equipment to underneath the shirt. We could still use these resources as a ‘what not to do when attaching cardiac monitoring leads’ teaching point.

How does this case study relate to the Hallmarks and Attributes you have selected?

This activity strongly embodies the Liverpool Curriculum Framework’s core values, hallmarks of excellence, and graduate attributes:

- Inclusivity: At its heart, the project was driven by a commitment to equality and diversity in education. By creating an inclusive set of teaching images, the case study directly advances the core value of Inclusivity in curriculum design. It ensures that students learn in an environment that represents all communities, thereby fostering respect and cultural competence. The activity helps “level the playing field” for BAME students (who see themselves reflected in the curriculum) and for BAME patients (by training future doctors to be equipped to care for them). This aligns with the university’s aim to promote equity and social justice through its programmes.

- Research-connected teaching: The genesis and execution of this activity were grounded in research. I identified the problem by engaging with the latest literature on health disparities and medical education – for instance, noting published evidence of underrepresentation and its consequences. Using that evidence, I formulated an innovative solution using AI and having support from CIE. Throughout, the approach exemplified scholarship in teaching: we not only applied research findings but also contributed to pedagogical knowledge by evaluating a new method. In effect, the teaching was informed by and interwoven with real-world research and development, fulfilling the hallmark of research-connected teaching which ultimately benefits the student.

- Active learning: The introduction of these AI-generated images will encourage a more active learning style. Instead of passively accepting textbook images as universal, students will be able to actively compare presentations across different skin tones. This can be incorporated into the pre session learning and teaching sessions delivered and could prompt the question of “How would this sign look on a darker-skinned patient? Let’s examine this image and find out.” Such activities required students to engage, observe, question, and deduce – characteristics of active learning. By grappling with diagnostic challenges in diverse contexts (rather than rote learning a single presentation), students became active participants in knowledge construction. This pedagogical shift resonates with the Active Learning hallmark, as students moved beyond memorisation to application and analysis in realistic scenarios.

- Authentic assessment and learning: Incorporating diverse patient imagery makes our teaching and assessment more authentic. Medicine in practice serves a diverse society, and our educational materials now reflect that reality more closely. For example, clinical OSCE stations or written exam cases can use these images of conditions on varying skin tones, making the assessment scenario much more true-to-life. This aligns with the hallmark of Authentic Assessment, which emphasizes real-world relevance in evaluation. Even outside of formal exams, the learning tasks (diagnosing from AI images, discussing cross-cultural cases) simulate actual clinical experiences students will encounter. By aligning learning activities with the realities of a multicultural patient population, the case study strengthens authenticity in the curriculum.

- Graduate attribute – Confidence: One graduate attribute we aim to instil is professional confidence. This activity contributes by expanding students’ comfort zone. Previously, new doctors might feel uncertainty when faced with an illness on an unfamiliar skin tone; now our graduates can approach such situations with confidence grounded in exposure and practice. Knowing that they have learned using diverse images gives students greater self-assurance that they can recognize conditions in many patients. This case study thereby nurtures confident, capable graduates who won’t be confounded by superficial differences in presentation. In the long term, this confidence can translate into more decisive and accurate clinical decision-making in diverse healthcare settings.

- Graduate attribute – Digital Fluency: Leveraging AI in teaching directly speaks to Digital Fluency, another key attribute for Liverpool graduates. Through this project, the educator team enhanced their digital capabilities and modelled the effective use of advanced technology. Students, in turn, will witness an example of digital innovation in their field. We hope to engage students in discussions about how the AI works or how it might be used ethically in future practice, thereby improving their digital literacy. By encountering AI as a learning tool, students became more fluent with cutting-edge digital resources and critically aware of both their potential and limitations. The case study thus supported the development of digitally fluent practitioners who can adapt to technological changes in medicine.

- Graduate attribute – Global Citizenship: The Liverpool Curriculum Framework aspires to produce graduates with a global outlook and a commitment to social responsibility. This activity reinforces those values by highlighting healthcare disparities and encouraging a broader perspective. Students learn that medicine is not “one-size-fits-all” and that being a doctor means caring for diverse populations with empathy and awareness. By addressing gender and BAME underrepresentation, we are educating future doctors to be attuned to issues of race, ethnicity, and inequality – competencies essential for global citizenship and working in a multicultural society. The discussions sparked by the case (for example, why certain communities have worse health outcomes, or how systemic bias can be countered) will help cultivate socially conscious professionals. In short, the case study promotes the graduate attribute of global citizenship by fostering cultural intelligence and a dedication to improving healthcare equity.

How could this case study be transferred to other disciplines?

Although rooted in medical education, the principles and approach of this case study are highly transferable to other disciplines. The common thread is using generative AI to address representation gaps and enrich learning materials:

- Health and Life Sciences: Beyond medicine, any healthcare field could adopt this strategy. For instance, nursing or physiotherapy programmes might use AI to generate images or scenarios featuring diverse patient populations (e.g. demonstrating nursing procedures on patients of different ethnicities, ages, or body abilities). In anatomy or pathology teaching, where textbooks often lack diversity in cadaver images or histology examples, with careful prompting and being mindful of the licensing limitations, AI could create illustrative variations (such as anatomical diagrams with different skin tones or depictions of how diseases manifest in different demographic groups). This ensures all health graduates gain a broad perspective on patient care.

- Social Sciences and Humanities: Disciplines like psychology, sociology, or history could leverage AI to diversify case studies and visual examples. For example, psychology lecturers could use AI images to portray people of various backgrounds expressing certain conditions or emotions, avoiding one-dimensional portrayals. History educators might generate images or even art of historical scenes with accurate ethnic diversity when real images are scarce – making history feel more inclusive of the people who were there. In each case, AI can fill content gaps and challenge stereotypes (imagine a history slide showing reconstructions of daily life in different ancient cultures side by side, created via AI).

- STEM and Engineering: In fields such as engineering, computer science, or architecture, generative AI can be used to visualize concepts in more inclusive ways. For example, an engineering design course could use AI to render diverse users interacting with a product, highlighting universal design principles (ensuring designs accommodate different body sizes, ages, or disabilities). Architecture or urban planning students could generate images of built environments with varied community demographics, fostering discussion on how design serves multicultural societies. This adds a valuable dimension of empathy and real-world complexity to technical fields.

- Business and Marketing: Representation is also crucial in disciplines like marketing, advertising, or business education. Case studies in marketing can be enriched with AI-created customer personas from diverse backgrounds, depicted in campaign mock-ups or user experience scenarios. This prepares students to consider a wider audience and avoid a narrow cultural lens. Similarly, leadership or management training could employ AI to simulate diverse team scenarios or workplaces, helping learners practice cultural competence and inclusion in organizational settings.

- Art, Media and Creative Fields: Art and media courses are already exploring AI for creative production, but they could also focus it on inclusivity – e.g. generating illustrations that include underrepresented groups in children’s literature, or storyboards for films that avoid common racial/gender clichés. By doing so, creative disciplines not only experiment with AI as a tool but also intentionally use it to broaden representation in creative outputs.

In general, the methodology of this case study – identify a representation gap, use AI to generate supplemental material, and integrate it thoughtfully into teaching – can be adapted to almost any subject. Key to success is maintaining academic oversight (to verify the accuracy/quality of AI outputs) and aligning the use of AI with learning objectives. If those conditions are met, educators in other disciplines can similarly enhance their curriculum. They can address biases (whether that’s ethnic, gender, socioeconomic, or otherwise) by creating more diverse examples, case studies, problem sets, or visuals. This not only enriches students’ understanding of the subject matter but also imbues lessons of inclusivity and innovation across the board.

It’s worth noting that transferring this approach doesn’t always mean generating images – AI could also produce text-based scenarios, data sets, or simulations to diversify course content. For example, a law course could use ChatGPT to generate fact patterns for cases that involve characters from various cultural backgrounds, if existing case studies are too homogenous. The flexibility of AI tools means each discipline can be creative in how they apply the concept. The overarching goal remains the same: broaden perspectives and better prepare students for working in a diverse world.

If someone else were to implement the activity within your case study what advice would you give them?

For educators looking to replicate or build upon this activity, here is some practical advice drawn from our experience:

- Start with a clear educational rationale: Identify the specific gap or need in your curriculum that AI generation will address (e.g. lack of diversity in images, scenarios, or data). Having a clear goal – such as “include more dark-skin examples in dermatology” or “showcase different cultures in case studies” – will guide your AI usage and help communicate the purpose to stakeholders and students. Always tie the use of AI back to improving student learning or experience, rather than using it for novelty’s sake.

- Pilot and refine: Begin on a small scale to pilot the approach. For example, start with one or two topics or a single module to integrate AI-generated content. This allows you to refine your process (prompt writing, verification, etc.) and gauge student responses. Use feedback to improve the quality and integration of the materials before expanding. In our case, piloting with a few dermatology images helped us troubleshoot issues (like refining image prompts) before we created dozens more.

- Collaborate with experts: If you’re not an expert in the content area of the images or scenarios (or even if you are), collaborate with colleagues who are. Their input is invaluable for validating AI outputs. In our project, having a dermatologist review image was crucial. Similarly, if implementing in another field, get a subject matter expert to check the fidelity of AI-generated examples. This not only ensures accuracy but also builds buy-in from peers (they see the value and are more likely to support and perhaps participate in the initiative).

- Understand the tool and its limitations: Spend time learning about the AI platform you’re using – what it can and cannot do well. Each generation model has quirks and knowing them will save time. For instance, image AIs might struggle with fine text or certain anatomical details; knowing this, you can avoid asking for something it won’t handle well. Keep your prompts descriptive and experiment with different phrasings. Don’t hesitate to use online communities or documentation for tips on effective prompt engineering. Being digitally fluent with the tool will make your implementation smoother and results better.

- Quality control is key: Always quality control the outputs before using them in class. This includes checking for factual/visual accuracy, appropriateness, and clarity. It’s easy to get excited by a very realistic-looking image, but ensure it truly represents what you intend to teach. Remove any AI artefacts or errors (you can sometimes edit images slightly to fix minor issues or just regenerate). If the AI produces any content that could be sensitive or biased, be prepared to discard and adjust your approach. Maintaining academic rigor in the content will uphold trust in your materials.

- Provide context to students: When introducing AI-generated content to students, explain it in context. Let them know why you are using these AI-generated images or scenarios and how it benefits their learning. In our experience, students appreciated understanding that these images were created to address a shortfall in traditional resources. This transparency could also turn into a learning point itself – students became curious about AI and its role in their field. Moreover, clarifying that an image is AI-generated can prevent any confusion with real clinical images and invites healthy discussion about authenticity and simulation in education.

- Integrate thoughtfully into teaching: Ensure the new materials are woven into your teaching in a meaningful way. They should complement and enhance your existing curriculum. Avoid simply dumping a set of AI images onto students without guidance. Instead, build activities or comparisons around them. For example, you might present an AI-generated case and ask students to solve it or use the new images alongside traditional ones to highlight differences. The goal is to enrich learning, so consider pedagogical strategies (discussion, quizzes, group work) that make the most of the AI content.

- Mind the ethical and copyright aspects: Check the usage rights of the AI-generated content (most platforms allow educational use, but it’s good practice to verify any licensing or guidelines). Ethically, remain sensitive to how different groups are portrayed – ensure the generated content is respectful and avoids reinforcing stereotypes. For instance, if generating images of people, try to depict them professionally and respectfully in a way that you would with real photos. Always use AI in accordance with your institution’s policies and general data ethics (even though these images are synthetic, maintaining professional standards is important).

- Be prepared for challenges (and critiques): As with any new method, be ready to encounter sceptics or technical hiccups. You might get questions like “How do we know these images are accurate?” or “Is this really necessary?”. Arm yourself with evidence (e.g. statistics or literature, as we cited in this case study) to explain the need and the benefits. Also, have a plan for technical backup – if an image turns out not as useful, have an alternative, or if the AI service is down, ensure it doesn’t derail your class. Incremental adoption can mitigate risk: you’re not dependent on AI for everything, just using it to enhance.

- Continuously evaluate and iterate: After implementing, gather feedback from students and reflect on outcomes. Did the inclusion of AI-generated content help students learn better or feel more included? Are there any misunderstandings or unintended effects? Use this feedback to iterate. You may find that continuous improvement (adding new images based on class needs, dropping those that didn’t work well, improving clarity) is part of the process. In this way, the project stays dynamic and responsive. If possible, measure impact in some way – even informally – such as improved quiz performance on related topics or student comments. Positive results will help sustain support for the initiative.

- Share your experience: Finally, don’t hesitate to share what you’ve learned with colleagues and the broader teaching community. As you implement your version of this activity, you’ll develop insights that could benefit others attempting similar innovations. Sharing could be through informal discussions, departmental meetings, or writing up a short case study or blog (as we have here). This not only contributes to a culture of innovation but can also provide you with helpful suggestions or collaborations for the future.

By following the above advice, an educator in any discipline can responsibly harness AI generative tools to enhance their teaching materials. The key is to keep the focus on pedagogical value and inclusivity. When done thoughtfully, the use of AI in education can be a powerful means to address longstanding gaps and prepare students for the diverse world they will engage with after graduation. Each step of implementation offers an opportunity to uphold academic rigor and creativity in equal measure – a balance that defines successful innovation in teaching.

References

- Adelekun, A., Onyekaba, G., & Lipoff, J. (2018). Representations of race and skin tone in medical textbook imagery. Social Science & Medicine, 202, 38–42

- de Vere Hunt, I., Owen, S., Amuzie, A., Nava, V., Tomz, A., Barnes, L., Robinson, J. K., Lester, J., Swetter, S., & Linos, E. (2023). Qualitative exploration of melanoma awareness in black people in the USA. BMJ open, 13(1), e066967. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2022-066967

- Lester, J.C., Jia, J.L., Zhang, L., Okoye, G.A. and Linos, E. (2020), Absence of images of skin of colour in publications of COVID-19 skin manifestations. Br J Dermatol, 183: 593-595. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjd.19258

- Louie, P., & Wilkes, R. (2018). Representations of race and skin tone in medical textbook imagery. Social Science & Medicine, 202, 38–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2018.02.023

- Lyman, M., Mills, J.O., & Shipman, A.R. (2017). A dermatological questionnaire for general practitioners in England with a focus on melanoma; misdiagnosis in black patients compared to white patients. Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology, 31(4), 625–628 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov.

- McFarling, U. (2020). Dermatology faces a reckoning: Lack of darker skin in textbooks and journals harms care for patients of color. STAT News, 21 July 2020 statnews.com.

- Roller, L. (2024, November 7). Illustrating change: Diversity in medical textbooks. Think Global Health. https://www.thinkglobalhealth.org/article/illustrating-change-diversity-medical-textbooks

- University of Bristol (2024). Students tackle gap in black and brown skin cancer diagnosis (Press release, 11 April 2024) University of Bristol News. Retrieved from: https://www.bristol.ac.uk/news/2024/april/students-tackle-gap-skin-cancer-diagnosis.html

Using AI-generated diverse clinical images to enhance medical education by Katrina Chadwick, written up with Rob Lindsay and Will Moindrot is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.