Many LIV.INNO students have the opportunity to spend a significant amount of time working in another location besides their home university as part of their PhD studies. In some cases, this is spending time working with an industrial partner who co-funds their PhD and in other cases it is working at other international laboratories around the world including CERN in Switzerland, FBK in Italy and Fermilab in the USA.

Several of the LIV.INNO students are spending an extended period at CERN. In some cases, their PhDs are co-funded by CERN and so they spend two of their four years there. Others spend a year there as part of a long-term attachment (LTA). There yet more who do not get to live there permanently but who are regular visitors!

In the University of Liverpool's QUASAR Group there are several students who are working on projects co-funded by CERN and so the students spend two of their four years at the laboratory on the French Swiss border. These students are all working on projects where there are also experts in their field at CERN so they can benefit from working alongside these people for two full years.

One of these students is Qiyuan Xu, whose PhD project is titled “Reconstruction of Transverse Beam Distribution using Machine Learning”. His work focuses on transporting light from a scintillating screen through a long, large-core multimode optical fibre to a camera placed in a low-radiation area. As the light propagates along the fibre, the original beam image is scrambled into a complex speckle pattern by mode coupling and other optical effects.

In the past, transverse beam distributions at CERN were often observed using radiation-hard Vidicon tube cameras installed directly in the beam line. However, production of these Vidicon tubes has now ceased, so different alternative diagnostics are being investigated. Qiyuan’s fibre-based, machine-learning approach is one of these possible replacements.

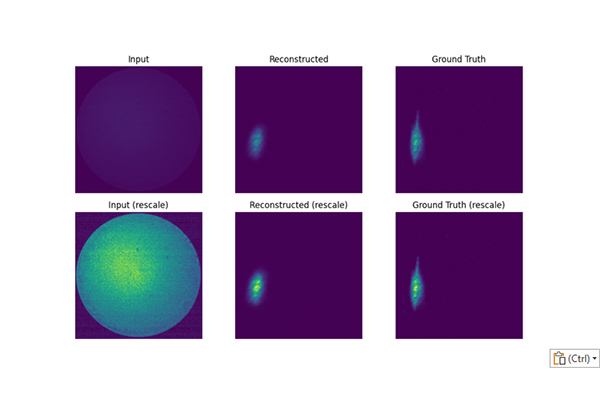

As can be seen in the image below, the pattern at the fibre exit looks very different from the original transverse beam distribution at the screen. Qiyuan is developing machine-learning models to reconstruct the in-situ beam distribution from this speckle pattern, using large synthetic datasets together with experimental measurements and his understanding of fibre propagation.

Before going to CERN, Qiyuan tested an early version of the setup in the DITA Lab at the Cockcroft Institute. At CERN he now has an optics lab with an optical table to develop and characterise the system. He has also had a dedicated beam time at the CLEAR facility to validate the method with real electron beam data. In the future, he plans to use the CHARM facility to study how radiation affects the fibre and associated components, so that these effects can be included in his models.

Beam images as seen at end of optical fibre (left), reconstructed (centre) and in situ (right).

In the University of Liverpool Particle Physics and Nuclear Physics groups students often spend a one-year LTA at CERN. Matthew Ockleton who is studying in the Nuclear Physics group is one such student. Matthew is studying ‘Developing Machine Learning methods to constrain the properties of the Quark-Gluon Plasma’.

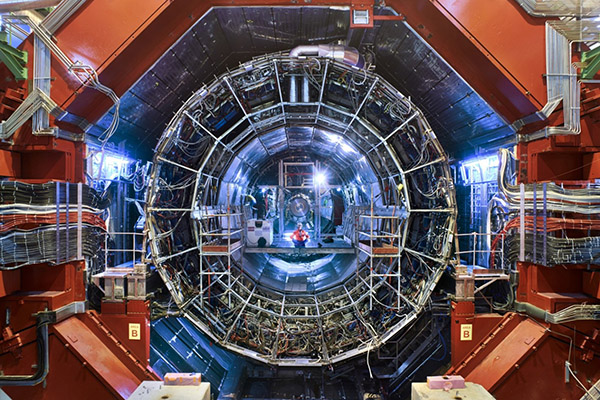

Matthew’s studies involve using the ALICE detector on the LHC and being based CERN means he has been able to take shifts on the ALICE detector during the LHC proton-proton data taking period as well as being able to work more closely with colleagues working on similar projects. He has also gained the opportunity to work with the ALICE Jet Working Group convenor on his data analysis which would not have happened if he were based permanently in Liverpool. During his time at CERN Matthew hopes to complete the proton-proton measurements he requires using the ALICE detector and contribute to the development of the new ALICE Inner Tracking System, ITS3. At the same time, he will continue to work with JETSCAPE to constrain QGP properties using data-intensive Bayesian methods.

The ALICE experiment is dedicated to the study of heavy ion collisions in which the Quark-Gluon Plasma (QGP) is created. In QGP, quarks and gluons are deconfined from their hadrons like what is believed to have occurred in the universe a split second after the big bang. However, the LHC program is dominated by proton-proton (pp) collisions. As a result, there is an abundance of pp data. This alongside well understood QCD theory allows the proton-proton collision system to act as a “vacuum” reference to lead-lead (Pb-Pb) collisions. Analyses construct the same observables in both pp and Pb-Pb collision systems, allowing modifications to be assigned to the presence of the QGP. Comparisons to Monte Carlo simulations based on different models allow the validity of different theories to be scrutinised.

One challenge in heavy-ion collision measurements is to identify signals within extremely large backgrounds. Modern data science techniques make signal identification possible with remarkable precision. Machine learning techniques are an essential tool for this process. Matthew has already used a boosted decision tree algorithm to identify candidates from background processes whilst also separating prompt (mesons made directly in the collision) from non-prompt (produced indirectly though other B-hadron after the initial collision). In the future, Matthew will explore using neural networks to distinguish between jets that form initially from a quark to jets that formed from a gluon.

JETSCAPE, a multi-institutional effort to design and use the next generation of event generators to simulate the physics of ultra-relativistic heavy-ion collisions, has recently been allocated approximately 13 million core hours on the Cambridge CSD3 supercomputer. Matthew’s benchmarking tests on the performance of the JETSCAPE software on this facility directly led to this large allocation, which he is now using to constrain properties of the QGP using advanced Bayesian modelling.

The ALICE detector on the LHC at CERN. Photo credit: CERN

Mehul Depala who is studying in the particle physics group is another student who is currently on an LTA at CERN. Mehul is using the ATLAS detector to see if any evidence of the theorised leptoquark particles can be found for his project ‘Leptoquarks at ATLAS Run III’.

Mehul has also taken advantage of being physically present at CERN by completing over 30 shifts on the ATLAS detector during his time there. In particular, he has worked on the Run Control/Trigger and Muon shifts, which are responsible for data acquisition and the operation of the muon sub-detector, respectively. Mehul has also taken on responsibilities as a CERN guide, an important outreach role that allows him to share the exciting scientific prospects explored at CERN with the public. His time at CERN has also enabled him to get to know many people within the ATLAS collaboration and the wider CERN community.

Leptoquarks are a hypothetical particle motivated, in part, by the similarity between family structure of leptons and quarks. More recently, a significant focus has been given to leptoquark searches due to anomalies detected by the BaBar, Belle and LHCb collaborations in rare decays of B-mesons which can be explained by the existence of leptoquarks.

There are three production mechanisms for leptoquarks: single resonant, non-resonant, and pair production. Mehul’s search focuses on pair production, as this involves production via QCD processes only and is therefore model-independent, with the cross-section depending solely on the mass of the leptoquark. The analysis aims to exploit the larger Run III dataset, the higher centre-of-mass energy (CoM), and the improved flavour and tau tagging algorithms, along with a dedicated phase-space search strategy, to enhance sensitivity and extend the current exclusion limits or find evidence of the particle. Mehul says that even finding evidence of one such particle would be valuable, as it would point the particle physics community toward physics beyond the Standard Model.

The ATLAS control room where Mehul Depala has completed over 30 shifts.

Qiyuan, Matthew and Mehul are just three of over ten students who will spend extended periods at CERN or other international laboratories as part of their LIV.INNO PhD studies. The benefits of spending the extended time in these places are numerous and the experience will be valuable to the students for their future careers.