Prosper career development pilot: ensuring a diverse cohort

Posted on: 24 June 2021 by Dr Peny (Panagiota) Sotiropoulou, Prosper Evaluation Researcher in Blog posts

As 53 postdocs join our career development pilot, we reflect on the final make-up of this first cohort and the process of recruiting these participants

As the final postdocs step on to our first career development pilot, this seems like an ideal time to reflect on the final make-up of this first cohort and the process of recruiting these participants – what went well, bumps in the road and lessons for recruiting our next cohort in September this year.

When applications opened back in December 2020, our aim was to recruit a diverse pool of 50 postdocs from the University of Liverpool to co-create Prosper with us through a programme of intensive career development. We knew that only through bringing together a wide range of researchers could we truly test our evolving approach to career development to ensure it works for all postdocs. Ultimately, we were able to offer 57 postdocs a place on the cohort, and 53 have now joined us. These postdocs were selected based on their ability to demonstrate why joining the pilot at this stage in their careers would benefit them, as well as showing how their specific circumstances and experiences would contribute to the co-creation of Prosper into something that is flexible, accessible and appealing to the broadest possible range of postdocs. Their applications were reviewed by a diverse panel that included members of the Prosper Board, Principal Investigators, representation from employer partners and the university’s Diversity and Equality team, plus an external postdoc.

Ensuring a diverse cohort

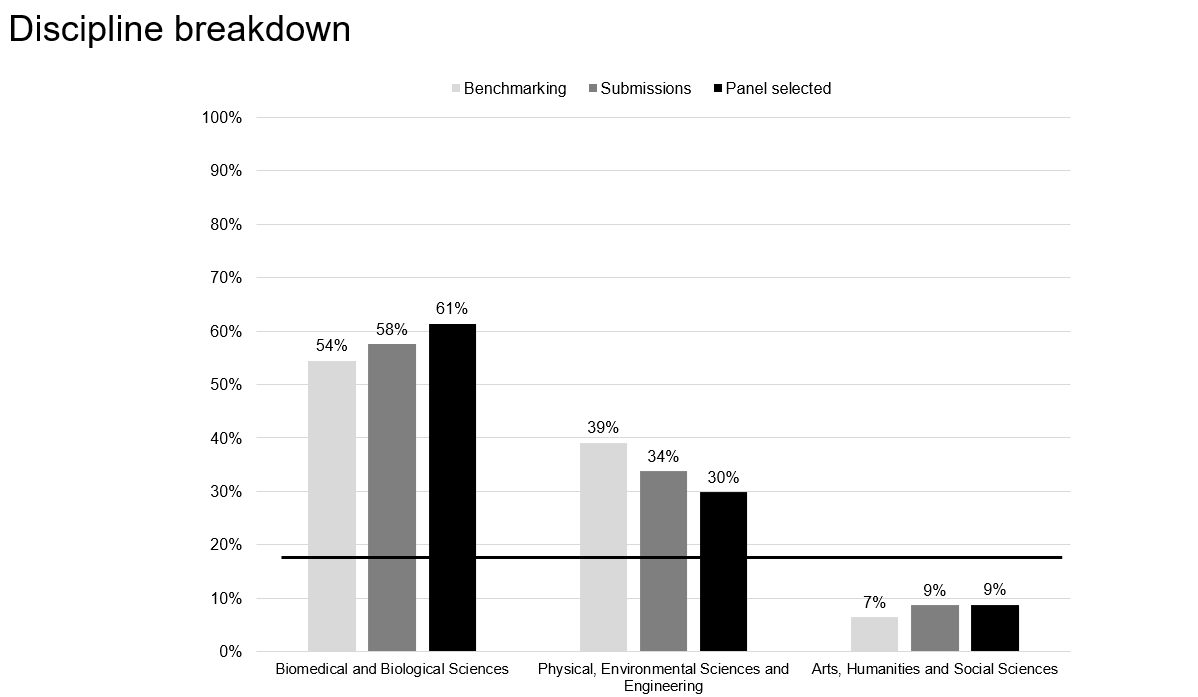

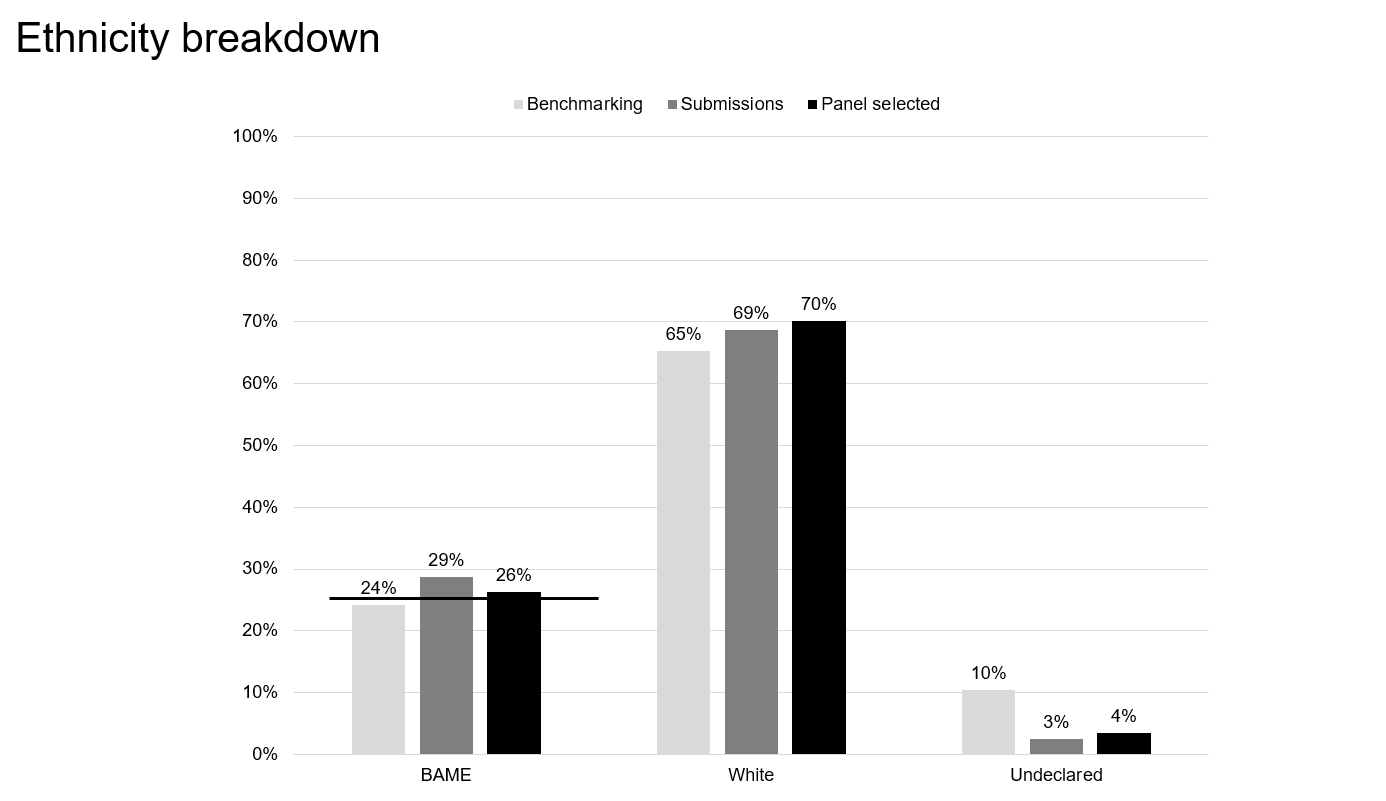

To meet our aims of testing Prosper’s offering for all postdocs, we began the recruitment process with aspirational minimum targets for gender, ethnicity and disciplinary background representation. Our targets are a reflection of our previous postdoc population benchmarking work using HESA data to look both at the national picture and the 3 Prosper partner institutions; the Universities of Liverpool and Manchester and Lancaster University.

We also entered the recruitment process with an eye to other diversity characteristics, such as disability, caring responsibilities and sexual orientation, to ensure our final cohort reflected the broad diversity that we know exists in the postdoc population.

Minimum targets:

- at least 20% representation from each of the three broad disciplinary areas below

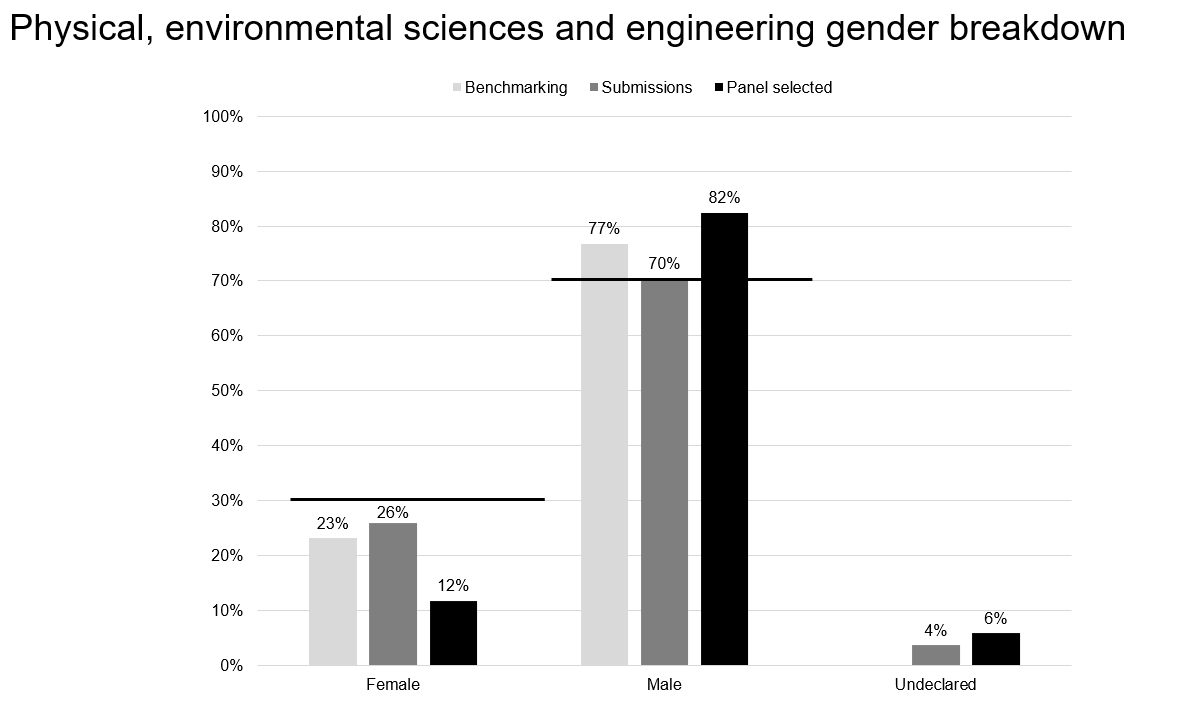

- Overall 50-50 gender representation, with further gender by disciplinary area targets:

-Biomedical and Biological Sciences - 50% female / 50% male

-Physical and Environmental Sciences and Engineering - 30% female / 70% male

-Arts, Humanities and Social Sciences - 60% female/ 40% male

- 25% representation from BAME postdocs

It’s worth bearing in mind that these targets are set for overall representation across both of our cohorts, the second of which begins next February and will include postdocs from across the 3 Prosper partner institutions. So, how did we fair against these success targets in our first cohort?

Discipline make-up

Out of the 57 postdocs who have been invited to join the pilot, 61% are from the Biomedical and Biological Sciences, 30% from Physical and Environmental Sciences and Engineering and the remaining 9% from Arts, Humanities and Social Sciences. The low share of postdocs from the latter group speaks to the size of the overall postdoc population in this disciplinary area. We were pleased to discover that we actually overrecruited from this area (Arts, Humanities and Social Sciences postdocs represent 6.5% of the overall University of Liverpool postdoc population, but make up 9% of the Prosper cohort invited participants) and we will seek to further boost representation from it in Cohort 2.

Gender make-up

In terms of gender, the 57 postdocs invited to join cohort 1 comprised of 53% female, 47% male and an additional 2% who preferred to not disclose this information. This is not far off our aspirational equal gender split, especially if we take into consideration that due to the small size of the cohort, a difference of 2 percentage points roughly represents one person. The gender ratio of both the participants who applied (55% female) and those that were finally invited to join Prosper (53% female) is higher than that of the University of Liverpool’s total postdoc population, as women form the minority there (44% women). Previous research has attributed the increased participation of women in career development programs to them seeking out sources of career advice and support to counterbalance inequalities arising from unevenly distributed informal career advice by PIs and institutions. We consider our women-majority cohort a win, aligning with educational and institutional policy initiatives aimed at improving women’s access to career development opportunities.

Looking further into our gender by disciplinary area targets, the distribution of the invited participants was as follows:

- Biomedical and Biological Sciences: 71% female, 29% male

- Physical and Environmental Sciences and Engineering: 12% female, 82% male, 6% prefer not to answer

- Arts, Humanities and Social Sciences: 60% female, 40% male

Despite the small number of cohort participants from Arts, Humanities and Social Sciences, we reached our gender target in this area. In Biomedical and Biological Sciences, the higher proportion of women was noted both at the submission stage (72%) and within the successful participants, and follows the women-majority trend in the overall population in this disciplinary area at the university (56%). Of note on this front was the drop in female representation from the Physical and Environmental Sciences and Engineering between the submission (7 applicants were women, which represents 26% of the applications received from Science and Engineering) and successful application stages (2 successful applicants were women, 12% of the total successful applicants from Science and Engineering). We did note that unsuccessful women applicants from this area were less likely to have attended one of our information drop-in sessions during the recruitment window; attendance at these was strongly related with successful applications. It also seemed that these applicants had been able to dedicate less time to their applications, based on how close to the deadline they were submitted. This left us pondering why women in the faculty seemed to lack time to effectively engage with Prosper and has given us some useful pointers for our plans to increase our intake in this area for the second cohort.

Ethnicity make-up

Out of the 57 participants invited to join the first Prosper cohort, 70% self-identified as white, 26% chose one of the ethnic groups that comprise the broad BAME category, while 4% chose to not disclose this information. Comparing the BAME invited cohort participants (26%) with the percentage of BAME postdocs in the total University of Liverpool postdoc population (24%) shows that we overrecruited from this target group, exceeding our minimum target for representation. We’re hopeful that this indicates that the targeted engagement we undertook, including our collaboration with the BAME staff network, paid off. This representation also aligns with our commitment to address the barriers to engagement with career development opportunities that we know BAME colleagues face.

To conclude, we feel that both the design and execution of the recruitment process was broadly successful and although we must address some representation issues for the next cohort, the targets that we did not quite hit came from areas that we had identified as problematic in our initial benchmarking data.

As we prepare for recruitment of the second pilot cohort across the three Prosper institutions, we’ll be planning our tactics to ensure we maintain and build on our successes (such as BAME representation), but also to improve shortcomings, like increasing representation from Arts, Humanities and Social Sciences, as well as from women in Physical and Environmental Sciences and Engineering.

Other EDI characteristics: disability, sexual orientation and caring responsibilities

Disability figures in academia are generally low, as counts are based on self-declared information. To give a sense of the under-disclosure of disabilities in UK HEIs, according to the most recent national statistics, around 8% of the country’s employed population has a disability, which means that the 4% currently declared amongst postdocs both nationally and across our 3 partner institutions is likely to underrepresent the real picture on the ground. Despite this, at least 10% of our cohort declared some form of impairment, health condition or learning difficulty. We’re pleased to have such strong representation of postdocs with these characteristics joining us to test and evolve Prosper with their input.

Similarly, we’re pleased by the number of cohort members who declared caring responsibilities (26% of successful participants) and those who are gay or bisexual (9%) and we’re excited about the perspectives they can bring to co-creating Prosper in the most inclusive way.

Stay tuned for further blog posts exploring how our cohort participants are experiencing their Prosper journey!

Keywords: postdoctoral reseacher, Prosper, R&D , research culture, covid-19, postdoc , economy , employers .