Vindaloo, Victorians, and Ancient Greek Colonisation Part 2: Intermarriage

Posted on: 21 February 2020 by Rohini Chavda, Muhammad Abbas Ghafoor, Saif Shah in 2020 posts

While studying Ancient Greek Colonisation and British Imperial Thought (ALGY 336) we examined the theme of intermarriage between Greek settlers and the ‘Barbarians’ they met. Archaeologist Anthony Snodgrass examined parallels between this and the British Empire, arguing that marriage between British officers and local women as positively encouraged in Calcutta (now Kolkata) and Burma (now Myanmar) during the early British Empire but it was later outlawed when Victorian pseudo-scientific ideas about race appeared. The same was true of the ancient Greeks. According to Aristotle, the founder of Massalia (now Marseilles) married a local Celtic princess but after the Persian Wars Greek attitudes to ‘Barbarians’ solidified and became negative.

Our own experience as British Asians is that there is much more to marriage than just race, or even faith. There are many different faiths, languages, and cultures within the Indian Subcontinent and each has its own attitudes and traditions surrounding marriage. In India, and to a lesser extent Pakistan, caste can still be a barrier to marriage. Arranged marriages sometimes do still happen and the motivation behind them is often economic – to bring the family wealth or a stake in a successful business – but this isn’t touched upon in the academic literature about Greek intermarriage, which remains fixed on ideas of race and culture because of the discipline of Ancient History’s enduring colonialist legacy. Prejudice only brings hate and negative actions but this module aims to help us steer our way through previous imperialist thought and explore other, more modern ways of thinking about differences we that we all encounter in the modern world.

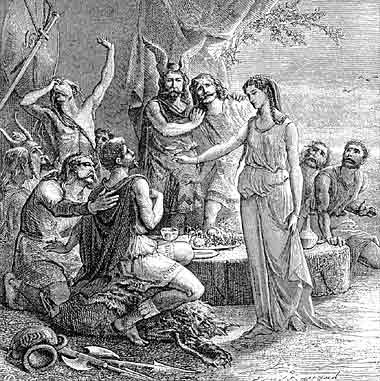

Gyptis, daughter of the local Celtic king, chooses the Greek Protis to be her husband. Engraving from the 19th century, from L’Histoire populaire de la France.

In our experience, it was a difficult adjustment for many Asian families migrating to the UK to adapt their traditions to the liberal, British way of life. Asian girls in particular who were taught to honour their family by following traditions from their homeland, including marrying into a respectable family chosen by their father. Rohini writes: “From my own experience, I was lucky to be born into a female empowering and dominated family whereby our freedom was encouraged. When introducing my white partner to my family, my father faced many questions from disapproving outsiders who identified my actions as scandalous, illustrating the existing sensitivity around intermarriage.” In many traditional societies it is believed that women will carry cultural traditions into the future generations and this was also true in ancient Greece where women were responsible for raising children and educating them in religious matters in the home.

In traditional Asian families there are still big differences in how boys and girls are treated and who a girl marries is more closely scrutinised than a boy. Discussion of gender is therefore something we’d like to see more of in the module in future.

Discover more

Read part one of Vindaloo, Victorians, and Ancient Greek Colonisation.

Study in the Department of Archaeology, Classics and Egyptology at the University of Liverpool.

Keywords: Vindaloo, Victorians, Ancient Greece, Empire, History, Ancient History , student, intermarriage, University of Liverpool, Equality, Diversity and Inclusion.