Update on fleas

John McGarry PhD MsC

Published October 2019

Updated September 2021

Introduction

Despite increased research and development of control products over several decades, domestic fleas – the most important ectoparasite of dogs and cats worldwide – continue to torment companion animals and to infest homes. The most recent practice-level survey in the UK has shown that some 28.1 per cent of cats and 14.4 per cent of dogs are infested in early summer, and predictably that some 90 per cent of recovered fleas – from both cats and dogs – are the cat flea Ctenocephalides felis. Other studies in the past 10 years have confirmed high rates of infestations of 12 to 47 per cent in some European countries.

Cat flea populations vary considerably from year to year, but with a consistent tendency to increase from spring to autumn. The flea life cycle is ‘nest-adapted’, unique in being able to survive low temperatures and situations where their host comes and goes; not only can the cat flea be found in houses in the colder months of the year, fleas may still be present in premises that have been left unoccupied for several months.

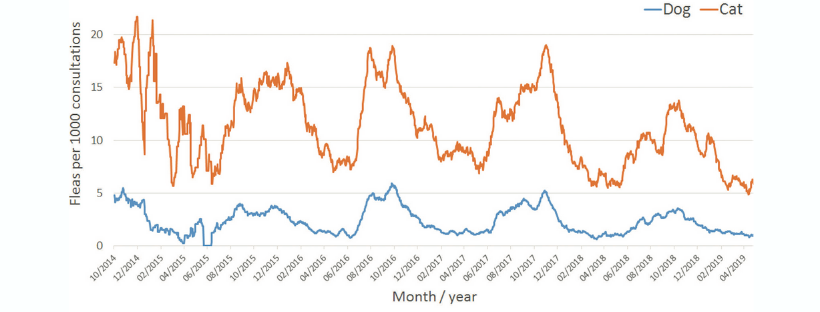

We have provided a simple summary of clinical narrative mentions of ‘fleas’ or ‘flea dirt’ between 1 October 2014 and 30 April 2019 in Fig 3. A 10-day moving average of flea mentions per 1000 canine or feline consultations, respectively, has been employed, excluding any days where fewer than 1000 total consultations were collected by SAVSNET in each respective species. It can be seen that flea prevalence has a clear seasonal pattern, that fleas can be found on dogs or cats in any month of the year, and that fleas are more frequently recorded in EHRs for cats than dogs.

Flea infestation records per 1000 dog and cat consultations expressed as a 10-day rolling average, as recorded within the free text clinical narrative collected by SAVSNET between October 2014 and April 2019. Days collecting fewer than 1000 total consultations were excluded from the analyses

Besides direct skin damage caused by frequent blood feeding, fleas can cause a flea allergic dermatitis in susceptible cats and dogs, and also serve as an intermediate host for the tapeworm Dipylidium caninum. But perhaps less well known is the flea’s potential worldwide to transmit pathogens – for example, Yersinia pestis (plague), Rickettsia typhi (murine typhus), Rickettsia felis (flea spotted fever), Bartonella henselae (cat scratch fever) and myxomatosis in rabbits. In the UK, Abdullah and colleagues13 recently demonstrated that 14 per cent of pet fleas carry at least one pathogen and approximately 11 per cent were positive for Bartonella species, which is also of public health concern.

Clinical signs

The vast majority of affected pets suffer from irritation and pruritus; they continuously scratch, groom, lick or vigorously nibble at the coat. Some cats are able to withstand infestation by hundreds of parasites and only express mild pruritus, whereas others present with allergic dermatitis with only a few fleas. Other clinical signs are more specific to cats, such as miliary dermatitis, which is defined by numerous papules and small scabs on the back and around the neck. Self-inflicted injuries are also possible and hair loss can be seen on the abdominal area, legs, flanks or tail as a result. In heavy infestations, animals may be anaemic.

Diagnosis

Definitive diagnosis relies on finding fleas in the coat, focusing on the tail, ventral face and neck areas in particular. Evidence of flea presence by finding flea faeces however is somewhat easier than seeing the fleas themselves: ‘flea dirt’ appears as small semicircles of shiny black grit up to 1 mm in length, and when placed on dampened blotting paper, colour the paper red due to the blood-rich diet of fleas. A diagnostic suspicion may be helped by questioning the pet owner: it is not unusual for family members in the affected household to complain about insect bites, which often appear in a series of marks on the legs and ankles. It should be remembered that fleas other than cat and dog fleas may cause problems. Those associated with rodents, birds and hedgehogs may be found on pets and bite people, complicating control programmes.

Treatment and control

Details of integrated flea control programmes are available elsewhere (www.esccap.org/ guidelines). Eradication of fleas from pets and households can be a challenge but is achievable, sometimes requiring a timescale of several months, if basic rules and treatment intervals are respected. Briefly, in cases of existing infestations, a combination of methodologies is often recommended. Alongside application of a flea adulticide and concurrent use of an insect growth regulator to break the flea life cycle, regular mechanical hoovering to remove flea immature environmental stages is needed, especially in and around areas where animals sleep. Washing affected pet bedding at temperatures greater than 60°C is also recommended.

However, every situation requires a full ‘flea risk’ assessment – a bespoke plan which addresses the threat of reinfestation – by a thorough analysis of the behavioural life styles and movements of all in-contact animals. Control breakdowns do occur, sometimes linked to disregard of retreatment intervals following perceived poor outcomes. As such, time taken by the veterinary professional to explain the nature of the flea life cycle and in managing client expectations will always be time well invested.

There is now a plethora of flea adulticides on the animal health market, but two agents in particular – imidacloprid and fipronil – were perceived as the ‘holy grail’ when first introduced in the early 1980s, being formulated as convenient monthly spot-on applications, and replacing to a large extent the poorly targeted and neurotoxic organophosphates then in widespread use.

However, widespread pollution of UK waterways with fipronil and imidacloprid has been demonstrated recently, which frequently occurs at levels far exceeding accepted environmental thresholds and likely to cause ecological harm (Shardlow, 2017; Perkins et al. 2020). Over use of flea control products is implicated – an area of real concern for the veterinary professions.

Further studies in this area are therefore urgently needed, not least in exploring and defining those risk factors (age, breed, neutering status, geographical location for example) which might lead to flea infestations. In this way, vets may in the future provide better, balanced and evidence-based advice on the use of more targeted companion animal parasiticides, and moving away from blanket prophylactic applications

Killing fleas as quickly as possible is highly desirable, and the introduction in the past few years of the potent fast- acting systemic isoxazolines (fluralaner, afoxolaner, sarolaner and lotilaner) marks the latest advance in integrated control for ectoparasites of dogs and cats. This pharmaceutical class is very effective against fleas, as well as ticks, and trials are showing high efficacy against a range of other common mange mites and ectoparasites. Although they do not prevent biting, cat fleas are killed in a matter of hours following a blood meal from a treated animal.

In the case of fluralaner, which is also formulated for topical use, therapeutic levels are maintained for up to three months (thereby reducing owner compliance issues). In addition, an enduring potent impact at sublethal levels on flea reproduction has been demonstrated experimentally, with the high potential therefore to break the natural flea life cycle in the domestic setting.

Read our surveillance report with a focus on fleas here.

References

Abdullah S, Helps C, Tasker S, et al. Pathogens in fleas collected from cats and dogs: distribution and prevalence in the UK. Parasit Vectors 2019;12:71

Halos L, Beugnet F, Cardoso L, et al. Flea control failure? Myths and realities. Trends Parasitol 2014;30:228–33

Perkins, R. et al. (2020) ‘Potential Role of Veterinary Flea Products in Widespread Pesticide Contamination of English Rivers’, Science of The Total Environment. Elsevier B.V., 750(1), p. 143560. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.143560.

Shardlow, M. (2017) Neonicotinoid Insecticides in British Freshwaters. Buglife - The Invertebrate Conservation Trust. Available at: https://cdn.buglife.org.uk/2019/10/QA-Neonicotinoids-in-water-in-the-UK-final-2-NI.pdf.

Williams H, Young DR, Qureshi T, et al. Fluralaner, a novel isoxazoline, prevents flea (Ctenocephalides felis) reproduction in vitro and in a simulated home environment. Parasit Vectors 2014;7:275