My Little Samurai – The Story of the Boy Who Didn’t Live

Posted on: 9 November 2020 by Athanasia (Nancy) Francis in 2020 posts

“I remember that day”, said one of Ekai’s fellow trans activists who Athanasia (Nancy) Francis, PhD candidate in Hispanic Studies, collaborates with in her research, recounting the events of 15th February 2018. “I was in class, had my phone on vibration, and the notifications on our Whatsapp group just kept coming non-stop. My friends’ profile pictures were turned black. I had a feeling that something bad was happening- something really bad. I left class and called a friend to find out. I just couldn’t believe it…”

Ekai had taken his own life at the age of 16.

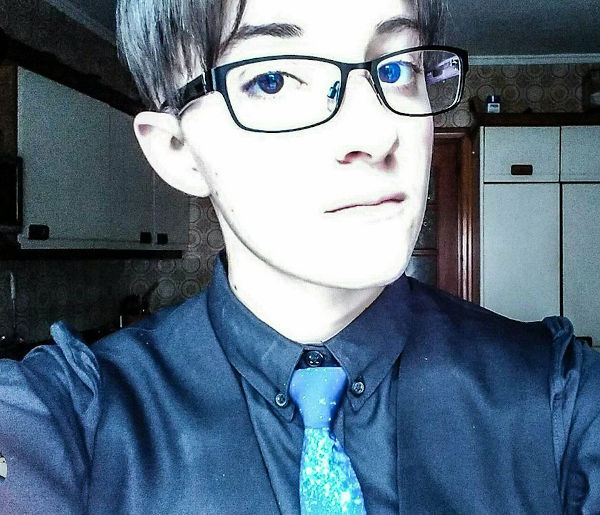

Ekai, was a teenage boy from Ondarroa in the Basque Country. He came out as trans to family and friends in 2017, and through the support of his parents, Ana and Elaxar, Ekai sought to take his first steps into his transition, in what they had hoped to be a straightforward path. At school, teachers and schoolmates had already started using his preferred name and pronouns, and expressed their support and admiration for Ekai’s courage to come out and seek visibility for trans people. Ekai started to openly share his experience as trans, in the hope that this insight would help the other trans youth in the schooling system. Yet, the real challenge for Ekai and his family came when he began to seek medical support to transition.

“It started to get bad when we entered the healthcare system”, recalls Elaxar in the documentary about Ekai’s story Mi Pequeño Gran Samurai (2019), directed by Arantza Ibarra. This is a reflexion on the experience of dealing with the healthcare protocols and procedures in place at the busiest healthcare unit in the Basque Country, Cruces Hospital, whose gender clinic is where trans people are directly referred to. In my observations as an activist researcher, as a worried friend and ally, and a partner of a trans person, it was clear that the system was failing trans people. It is indicative how in informal chats amongst the local trans community members, the name “Cruces” was invested with negative connotations; “Cruces” had become a euphemism for the unattainable, the tormenting, an infinitely prolonged wait in a Kafkaesque scenario of pointless institutional interaction. Of course, the problem was not a single hospital, but rather the healthcare system in place which had not been designed to accommodate the needs of trans people – in some cases in fact, as it becomes evident in the documentary, it didn’t even acknowledge their existence.

Ekai was seen by mental health professionals and was reassured that he would be supported by suitable medical staff. However, Ekai was never seen by an endocrinologist to discuss the option of hormone treatment, which was what he had explicitly desired since coming out. Instead, he ended up caught in a series of consultations lasting over a year, encouraging him to seek alternatives to transitioning or, as stated in the documentary, to learn how “not to sweat the small things”. Ekai eventually took his own life while still on the waiting list for hormones.

Ekai’s parents have since been active in initiating discussions about trans support and the changes necessary to achieve it. “Being trans is not a mental illness”, points out Elaxar in an interview about the loss of his son, “it must be depathologised”.

A whole new community came together on the day of Ekai’s funeral, people of all ages and from all walks of life, from different neighbourhoods, towns, countries. They had gathered around a big heart traced using red candles with his name in the middle; they were bonded by a sinking feeling and the wish to say their last goodbye to a boy that should have lived. I go back to my notes and the recollections of other people’s accounts of Ekai’s funeral. Some of the details sound rather trivial but these are the ones that affect me the most. The crowd singing the famous Mikel Laboa song 'Txoria- Txori' (A bird’s a bird), originally a poem inspired by the resistance against fascism during Franco’s time. It was hard to miss how the lyrics had now been enriched with additional meaning - albeit painful - attributed by the tearful singing crowd, and the eery flapping of the birds choosing that moment to fly over it:

Hegoak ebaki banizkio

Neria izango zen

Ez zuen aldegingo

Bainan, honela

Ez zen gehiago txoria izango

Eta nik... txoria nuen maite.

(If I had cut its wings

It would have been mine

It wouldn’t have escaped

But then,

It would no longer be a bird,

And I… loved that it was a bird.)

A screening of the film Mi Pequeño Gran Samurai (2019) is taking place on 20 November 2020, at 7pm, sponsored by the Basque Society in London and the Basque Studies group at UoL to commemorate Transgender Day of Remembrance 2020. Book your free online ticket.

Discover more

Study in the Department of Modern Languages and Cultures at the University of Liverpool.

Keywords: my little samurai, lgbtq+, basque studies, hispanic studies, spain, transgender day of remembrance, lgbt, mi pequeño gran samurai.