Depression, status quo bias and the Brexit referendum

Posted on: 17 February 2020 by Luca Bernardi (University of Liverpool) and Robert Johns (University of Essex) in 2020 posts

Dr Luca Bernardi (Lecturer in Politics at the University of Liverpool) and Professor Robert Johns (University of Essex) examine the impact of depression on the public's voting decisions, with a particular focus on the 2016 EU Referendum.

According to NHS statistics, depression is the second most common medical condition in England – ahead of obesity and behind only high blood pressure. And this is only diagnosed depression. Public Health England estimates that just half of those presenting to their GPs with depressive disorders have their symptoms recognised. Its sheer scale makes depression a part of British society.

Yet it is rarely thought of as part of British politics, let alone included among likely influences over people’s voting decisions. This might be an oversight. Depression affects the way people interpret information and reach the kinds of judgements central to electoral choice.

Depression has a particular impact on reactions to change. Summarising and simplifying a vast range of psychological research, here are four key points. Depression sufferers are:

- less motivated to research change and so more uncertain about its impact;

- more attentive to negative than positive information and so more pessimistic about that impact;

- prone to feel helpless and not in control of the consequences of change;

- risk-averse even in unfavourable situations, seeking mainly to avoid further losses.

The upshot can be summed up in three words: status quo bias. Since many electoral choices take the form of status quo vs. change, the potential relevance of depression is clear.

A case in point is the Brexit referendum of 2016. Based on the above, those with depression would have taken a dim view of the change involved in leaving the EU, and been sceptical about any prospect of ‘taking back control’. They should have leaned strongly towards Remain.

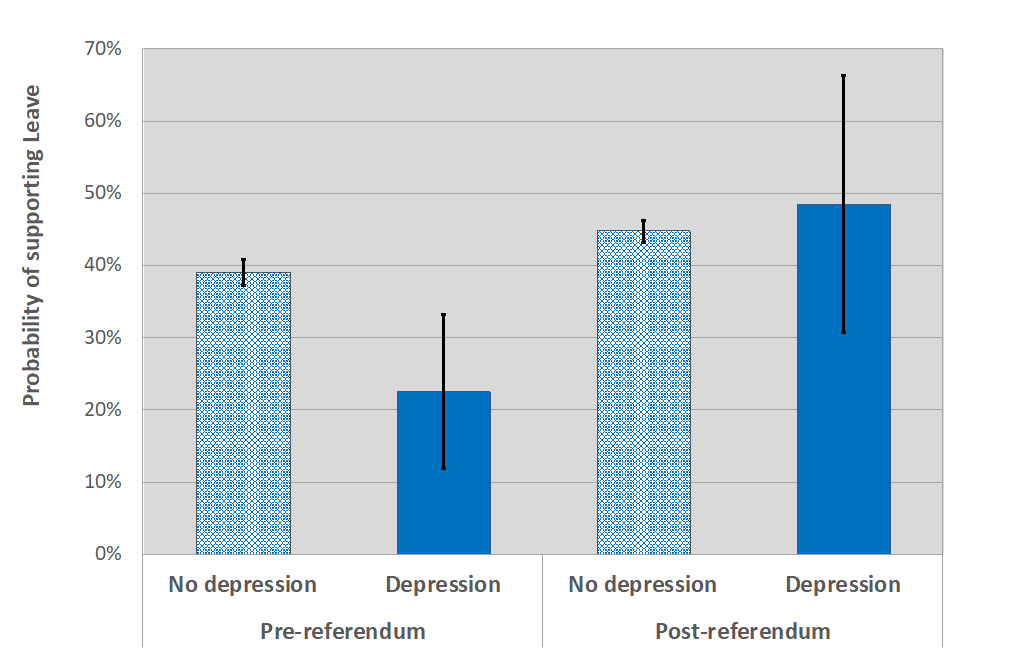

To see whether this is the case, we used data from the long-running Understanding Society survey which asked respondents if they had been diagnosed with clinical depression. The graph below shows the Brexit views of those with and without depression, depending on whether respondents were surveyed before or after the referendum.

In advance of polling, those diagnosed with clinical depression were indeed much more likely to support Remain. But that gap closed after the referendum. So it looks as if pre-referendum hostility to Brexit owed less to the substance of the issue and more to opposing the upheaval of change. Once the Leave vote had shifted the psychological status quo, depression sufferers were less inclined to support a Remain option that had in some ways become the disruptive change.

The results here suggest a striking impact of depression on political attitudes. Given the prevalence of depression, this is an impact on many people.

This study is based on just one case, and the number of depression sufferers in the sample was frustratingly small – only just over 1% of our sample of around 12,000 respondents. Understandably, those interested in clinical depression haven’t asked about voting behaviour – and vice versa. If we are to understand and address the political implications of poor mental health, this must change. Thus the customary plea for further research here is also a plea for new data.

Citation: Bernardi, Luca and Robert Johns. N.d. “Depression and attitudes to change in referendums: The case of Brexit”. Forthcoming in the European Journal of Political Research

Discover more

Study in the Department of Politics at the University of Liverpool.

The research of Dr Bernardi and Professor Johns will be featured on the BBC radio programme 'Do voters need therapy?' on Monday 17 Feburary. Listen on the BBC website.

Keywords: University of Liverpool, Politics, study, mental health, Liverpool, Brexit, depression.