Ghana

What is happening in Ghana with Cocoa?

by Leona Vaughn

Ghana, according to the International Cocoa Organisation, grows almost 20% of the world’s cocoa.

Cocoa from this region is therefore undoubtedly present in the supply chain for UK-based chocolate companies who are subject to the Modern Slavery Act 2015. Companies with a presence in the country include Nestle, Mondelez (Cocoa Life), Cargill, Divine, Barry Callebout and Ferrero.

However, the labour used to harvest this cocoa, in a context of predominantly small-scale farming, has been under intense scrutiny in recent times.

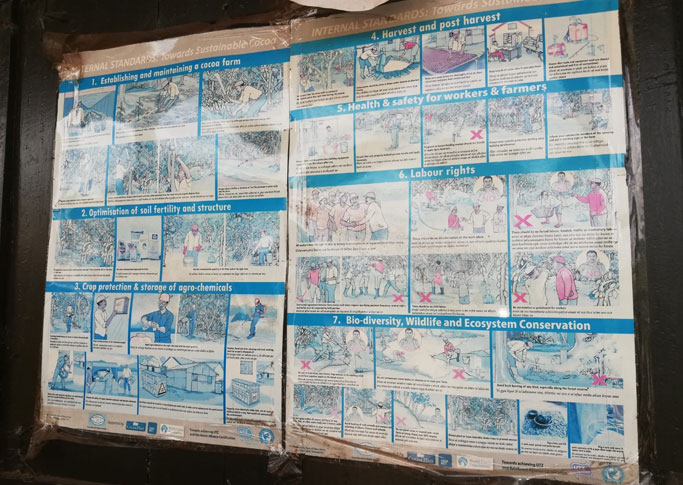

Image: Cocoa plantation and drying of cocoa beans, Ghana

There have been concentrated efforts to achieve ‘child labour free’ cocoa in Ghana, including Government actions to improve governance of cocoa production; make secondary education free to access from 2017 and establish Child Protection Committees in cocoa-growing regions.

The Global Slavery Index Cocoa report findings claim that between 2016 and 2017, of the approximate 708,000 children under the age of 18 working in cocoa, 94% were undertaking hazardous tasks (i.e. were in child labour) and around 14,000 were in forced labour.

Furthermore, the claim is that of the 1.1million adults working in cocoa at that time, around 3,700 were in forced labour.

‘Modern slavery’ appears to be a pressing issue in Ghana’s cocoa sector and one which should be uppermost in the minds of chocolate-producing companies, especially those subject to the Transparency in Supply Chain clause of the UK Modern Slavery Act 2015.

Ghana is now, in circumstances of continuing discoveries of gold and oil, classed as a ‘middle income’ country. Yet, struggles of poverty, poor sanitation and homelessness across a predominantly rural country remain.

Research which explores the experience of workers and stakeholders in this context can therefore only assist us to understand what impact, if any, work to improve transparency in this supply chain is having on people’s lived experiences.

What is My Role in This Project?

I am the Post-Doctoral Research Associate on this project. My role is to manage the relationships with our subcontracted research teams who are undertaking the fieldwork from a locally informed perspective in all four countries, Ghana, Myanmar, Dominican Republic and Bangladesh. I coordinate the management of data or information that is generated from this aspect of the project’s research and undertake the analysis.

In early November 2018, I undertook a visit to the research team that we have commissioned to undertake interviews with labourers, farmers and other stakeholders in the Ashanti region of Ghana. The team, led by Dr Albert Arhin at Kwame Nkrumah University for Science and Technology in Kumasi, facilitated this visit and organised a number of meetings and interviews for me to observe and contribute to.

Fieldwork in Ghana

Interviews were still taking place at the time of the visit, just at the end of the harvesting season. Some of the challenges to the fieldwork were discussed. Plantations are often in remote rural areas, with poor access roads. The fluidity of labour on cocoa farms, often related to the different needs of farms in different seasons, meant that researchers may not be encountering the full range of labourers involved in production all year round.

Labourers, primarily travelling from Northern Ghana (predominantly Muslim regions) and bordering countries such as Togo, were specifically identified as a group of workers that were not felt to be fully represented in the fieldwork. There was also little knowledge about whether this migration was organised or informal – i.e. how workers get to know about the work and if recruiters are involved. Whilst formal child labour had not been encountered in the fieldwork thus far, it was accepted that we do not know if or how the ages of this particular group of workers are verified.

There are over 250 languages and dialects spoken across Ghana alone. Researchers outlined the communication challenges and how they had been overcome for interviewing the small number of internal and external migrant labourers they had met.

We visited a local cocoa plantation and packing warehouse, observing the signs outlawing employment of children under 18, and the antiquated equipment and intense physical labour involved in the latter. This visit gave a unique insight into how Ghana is developing its ‘traceability’ of beans from the farm to the processing stage, through rigorous labelling and categorisation.

We met with non-governmental organisations working with cocoa workers and on children’s rights issues in the country who spoke of the work they have been doing to reduce child labour in cocoa production and outlined some of the challenges to addressing potential labour exploitation generally.

Image: Members of the research team, Albert and Favour, with Leona and staff from Defence for Children International (Ghana)

We spoke with Ghanaian stakeholders from the cocoa industry, including the local companies within the governance structure for the production and sale of cocoa, some of whom who work directly with international chocolate producing and certification companies, to gain some understanding of how the industry operates within this context.

Ghana is a complex landscape for researching cocoa production with a number of actors involved; State, private and non-governmental.

As a sociologist with an interest in children’s rights, risk and risk regulation, I personally gained an excellent awareness of the social and economic factors at play within this setting from a Ghanaian, rather than Eurocentric, perspective. Particularly important was the comprehension about how efforts to remove child labour from cocoa production altogether have been effective but are also having other, probably unintended, social impacts. The forthcoming analysis of the data from this and the other three countries, relating to both the cocoa and garment sectors, will be greatly enhanced by this insight.

Dominican Republic

Cocoa in the Dominican Republic: A Shifting Panorama

by Eve Hayes de Kalaf

Overview

The Dominican Republic (DR) grows around 1% of cocoa. Nevertheless, what the country lacks in quantity, it certainly makes up for in quality. The DR not only produces some of the best cocoa in the world, it is also a leader in the exportation of ‘ethical’ (i.e. Fair trade) cocoa.

Over the past two decades, the DR cocoa sector has grown exponentially and there has been a concerted effort to increment domestic production. In the 1980s, most cocoa was of poor quality and exported to the US. Today, the country complies with rigorous EU and Fair Trade standards. Cocoa is organically certified and shipped mainly to Europe.

.jpg)

Cocoa pods from Bloque 2, Conacado in Yamasá, Dominican Republic

Children and Cocoa

I visited the DR from July to August 2018 where I met with and interviewed over fifty NGO representatives, government officials, industry stakeholders, cocoa producers and workers. In contrast to Ghana (the other cocoa-producing country we worked with on this project), there is no child exploitation per se in the Dominican cocoa industry. This is not to say, however, that children and young people are entirely absent from the industry. It is not uncommon, for example, for children to informally participate in tasks on the farm. This is often described as a form of ‘helping out’ the family (‘una ayudita’) and is an integral and important component of rural life.

Many producers own small plots of land where cocoa production has largely depended on a strong domestic and communal unit to help with the harvest. In recent years, however, there has been a decrease in children working in the sector. This is partly because producers are faced with the threat of losing their certifications if child labour is identified on their land. In addition to this, the state has also extended the number of hours it requires children to stay in school. Whereas previously children were able to ‘help out’ more with cocoa production during the daytime, most are now in school and are therefore spending less time on their family farms.

Nowadays, young people who could stay and work in cocoa are instead moving away to bigger towns and cities in search of better paid employment or to study. Often the producers I spoke with lamented how difficult it was to pass on their farms to their families. There was a general consensus among stakeholders that because cocoa producers are not paid enough for their harvest, their children are being ‘driven away’ from the sector.

Cocoa Producers

Almost all producers are born poor and die poor. In general, most told me they were very dissatisfied and felt they were being exploited. Many expressed a lot of negativity about the future of the sector. Although farmers have spent decades meeting international standards, improving the quality of cocoa, reducing the use of chemicals and taking their children off the farms, they said they were yet to see tangible benefits to the changes they have been made to introduce. This was despite the fact that they continued to benefit from social projects, which included the building of wells, schools and sanitation systems for their communities.

There were also issues with land distribution. The country is gradually transitioning towards larger farms as smallholders are bought out by bigger commercial investors. When a producer dies, and if no family member is willing to take over the land, their relatives are much more inclined to sell the land for profit rather than continue working in cocoa. Farmers regularly struggle financially and take out loans to pay their workers. If unable to repay their debts, their land can be taken from them.

Cocoa Workers

Most of the labour on small farms is informal, seasonal and ad-hoc depending on the demand and the time of year. In contrast to producers who usually own their land, workers tend to move from one farm to the next, are paid daily or weekly and are often hired via word-of-mouth or by walking through neighbourhoods.

NGOs have tended to focus on the impact of cocoa production and the promotion of good practices from the perspective of the cocoa producers, rather than the workers on the farms. While this framing has ensured that labour standards and general conditions have improved across the sector, at times international actors and the commercial sector have not taken the experiences of cocoa workers and their families into account.

Nonetheless, the workers I spoke with told me that their conditions have improved significantly in recent years. Rigorous certifications and the implementation of international labour and safety standards had clearly play a role in this scenario. Workers (both Dominican and migrant) usually start in the morning at around 7.30 a.m. The day usually ends at 4 p.m. When working together, Dominican and Haitian workers are paid at the same daily rate and producers are expected to (and did, from our observations) provide them with lunch.

Migrant Labour

Cocoa in the DR is one of the rare sectors dominated by Dominican (as opposed to Haitian) workers. Traditionally, sugar and bananas have been associated with the ill-treatment and exploitation of Haitian labourers. The stakeholders I spoke with explained that cocoa is seen as a much more skilled industry in that farmers must have a specific level of technical knowledge to harvest the crop. Notwithstanding, the Dominican cocoa sector is growing increasingly dependent on a Haitian labour force. Five years ago, it was difficult to find Haitians working in cocoa. Although many migrant workers tend to do the weeding or unskilled jobs that Dominicans would not do themselves, more are acquiring these skills and remaining in the DR.

As this panorama changes, Haitian labour is likely to increase. Problems in sourcing younger labourers to work on plantations is taking its toll on the industry. Despite having access to the land, the contacts and the agricultural knowledge, young Dominicans do not see an economic benefit to working in the industry and are leaving the sector.

The Future of Cocoa Production

As we have seen, the current socioeconomic climate in the DR is relatively stable. Working conditions are on-the-whole fairer than in other parts of the world and the country is regularly portrayed as a model of good practice in the sector. While the DR has made admirable efforts to comply with EU demands to achieve certified organic status, however, many of the producers I spoke with remain unhappy. They feel they are not being listened to and many expressed concerns about the future of the sector.

The biggest problem the stakeholders I interviewed for this project identified is that in 20 years there will not be a big enough labour force to meet the demand in cocoa production. Many expressed clear resentment towards the dominance of European actors over the way in which the DR is expected to harvest cocoa as well as the amount that producers are paid to produce the crop.

As one stakeholder I spoke with asked, “Who is going to send cocoa to Europeans in the future? If not us Dominicans, then who?”

All photo credits to Alex Saint-Hilaire and Gabriel Alemany. Photos taken in Yamasá, Monte Plata, Dominican Republic.

Back to: Department of Politics