Prison records from 1800s Georgia show mass incarceration's racially charged beginnings

Published on

Barry Godfrey is Professor of Social Justice in the University of Liverpool’s Department of Sociology, Social Policy and Criminology

Henry Minter was working as a farm laborer in Georgia in the 1870s when he met Mary Dotson, a young black servant girl. The couple never married – which would have been illegal at the time – but they stayed together until Henry’s death.

Mary, who was left with their four children, then became a washerwoman in Atlanta. Their daughter, Florence, tried to raise funds by making moonshine. Caught in 1920, she served three years for illegally making liquor.

When Florence’s father was born in the 1850s, the state prison population was largely white. But, by the time she was imprisoned, the majority of prisoners were black.

Newly digitized records from the 19th and 20th centuries reveal the names and the stories of thousands of prisoners like Florence – as well as the racially charged beginnings of mass incarceration in the U.S.

Mass incarceration

In 2016, in the U.S., about 1.5 million people were in prison. Approximately 12 to 13 percent of the national population is African-American, but this group makes up over one-third of prisoners.

Why does the American prison system disproportionately imprison black men? Some analysts blame the war on drugs. But that wasn’t the start of the connection between race and imprisonment. Previous historical research shows that, after the Civil War, there was a significant rise in imprisonment of former slaves in the U.S.

The end of slavery also saw a rise in prison populations across the British Empire. Before the abolition of slavery in 1833, the West Indies had a prison population of approximately 1,000 inmates. By 1835, it had risen eightfold.

As in the British West Indies, the end of slavery in the U.S. was accompanied by a desire to incapacitate “problem” populations in other ways. As the future governor of Mississippi’s penitentiary stated at the time, “Emancipating the negroes will require a system of penitentiaries.”

Georgia’s prisoners

Ancestry.com has uploaded prison records to the internet, to satisfy genealogists searching for ancestors who may have been imprisoned. Thousands of digitized prison records are now available for not just the U.S., but also for Canada, the U.K., Australia and other countries.

We presented our research on digitized records of Georgia’s penal system at a workshop on prison history at the University of Georgia on April 10. Our analysis of nearly 25,000 prison register entries shows how connections between race and imprisonment started in the 1860s.

The records’ range of information for Georgia is impressive, running for 200 years from 1817. In addition to the name of the prisoner, the offense and details of the sentence, the records also include details like eye color, height, birthplace and place of conviction, as well as whether the prisoner was subsequently pardoned or escaped.

Before the Civil War, an average of 40 people a year were sent to prison in Georgia. Samuel W. Whitworth from Jones County was a typical prisoner. The blond and blue-eyed cotton farmer was jailed for causing “mayhem” – probably some drunken violence – on March 1, 1817. Sentenced to 10 years imprisonment, he managed to escape on Christmas Eve 1820. He was later recaptured and hanged in South Carolina.

As a white man, Whitworth was part of the majority at a Georgia prison. Between 1817 and 1865, records reveal that a fifth of inmates were described as “black,” “dark” or “copper.” The range of descriptors used to describe “complexion” – later swapped out for the category of “race” in 1868 – were impressionistic and casually derogatory. About 900 people in our sample were described as being the color of “ginger cake.”

In 1864, just seven former slaves were imprisoned in Georgia. By 1868, this had risen to 147.

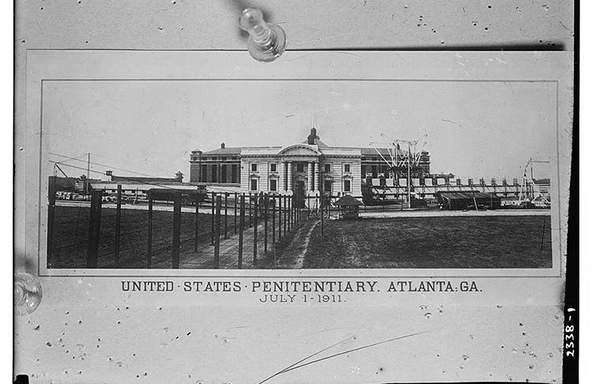

From the 1870s to the 1900s, sentenced prisoners were forced to labor in the fields, rather than stay inside prison walls. When this convict leasing system ended, the figures again rose inexorably upwards. The number of prisoners rose from 42 in 1900, to over 500 in 1910, to over 1000 by 1920.

Our research shows that the huge upswing in Georgia prison numbers throughout the 19th and early 20th century was caused by sweeping young black men through the prison gates. The increase in numbers was primarily due to a rapid and sustained influx of African-Americans between ages 18 and 22.

Stories in the data

Statistics can only take us so far. Using methods developed in a previous project on British convicts, Digital Panopticon, we have started to match together digitized trial reports, census records, prison documents and family histories in order to reconstruct prisoners’ lives before and after they were imprisoned in the system. Ultimately, we hope to make this research freely available online.

In our view, these people should not be defined either by their status as former slaves or as prisoners. They spent time in prison, but then were released to build their lives again.

For example, Rose Jackson, with 15 siblings, born in 1856, was convicted of stealing from her employer’s house in Muscogee, Georgia. She served six years inside the prison before resuming her life, never to be in trouble with the courts ever again.

James Wimley – described as a 5’ 4" black man – was convicted of theft at age 15 in Cobb County, northwest of Atlanta. Despite serving six years in custody, he went on to work on a farm, got married and had children. In 1909, he was still living with four of his children as a widower in the area now known as Cartersville City.

Prisoners like Jackson and Wimley often led successful lives on release, despite the inequalities of the system that had locked them up. When searching for employment and a place to live today, former prisoners of African or Hispanic descent may face similar problems to those faced by former slaves 150 ago.

![]() Black prisoners matter, even if historians have sometimes been blind to that. Thanks to these newly digitized records, researchers can now compare the lives of people who were imprisoned in Alcatraz, Kansas Leavenworth, Eastern State Penitentiary, and so on. Historians like ourselves are now equipped to reveal the names and stories of thousands of forgotten prisoners.

Black prisoners matter, even if historians have sometimes been blind to that. Thanks to these newly digitized records, researchers can now compare the lives of people who were imprisoned in Alcatraz, Kansas Leavenworth, Eastern State Penitentiary, and so on. Historians like ourselves are now equipped to reveal the names and stories of thousands of forgotten prisoners.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.