Bartleby: A Tale of Wall Street

The School of Arts have teamed up with WoWFest2021, with students from across the School previewing events from this festival of radical writing, taking place throughout May.

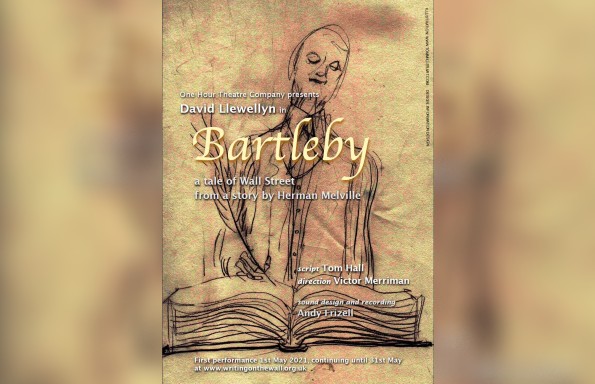

Richard Snowden-Leak (year 3, English) previews One Hour Theatre Company’s ‘Bartleby: A Tale of Wall Street’, free online until 28 May

Bored of Being Bored

Herman Melville’s ‘Bartleby, The Scrivener’ is a strange thing. One element of this strangeness is that for a story written in 1853, it is uncannily prescient in its depiction of boredom in the twenty-first century. One aspect of this boredom is a feeling that there is nothing new. Perhaps this is why One Hour Theatre Company is choosing to return to this classic short story with their WowFest audio drama project Bartleby: A Tale of Wall Street.

At one point in the early 2010s, all the apps looked the same. Facebook, Twitter, YouTube: they all had these soft, clean fonts, and similar website designs, user interfaces. Films were being released or rebooted, and old artists who made their name in the late 90s and early 00s were returning as well. In the Bartleby story, of course, there are no global corporations prying into our shopping lists and our Fitbits, but there are still recognisable aspects of capitalism as it is today. Here is another element of strangeness: 168 years after this story, the very same Wall Street was occupied in protest at the banking crisis of 2008. Occupy – much like how Bartleby occupies the Lawyer’s office in Melville’s tale: refusing to move, refusing to work, refusing to be bored, refusing to be bored of being bored.

In the original Bartleby story, when talking about a job offer elsewhere, Bartleby remarks: ‘There is too much confinement’. The Lawyer replies that Bartleby has been confined all this time in a room. Bartleby’s confinement is prophetic; it’s a cultural confinement. It’s being tied down to a job, a copywriter’s one at that, forever; it’s being tied to a society from which there is no escape.

We might see this claustrophobia more in terms of the all-pervasiveness of what Mark Fisher would call capitalist realism, the realisation that there is no political alternative. Look at how capital has pervaded all aspects of our contemporary life: go on the Appstore and the gig economy is booming. You can sign up to TaskRabbit, can offer your services on Fiverr. Every aspect of you, your skills, your body, can be sold and commodified now. Meanwhile, you as an individual are responsible for your own income, your own security (and precarity). In our cultural confinement we become isolated from others, and that isolation has only become intensified in lockdown, as the boredom of everyday life has been laid bare for all to see.

Even our own confinement and isolation from others has been commodified. There is an app called E-Pal where you can pay for someone to play games with you. And the treatment of the mental health crisis exacerbated by isolation has also been outsourced, with many institutions like the NHS resorting to sites like SilverCloud or Togetherall, putting the onus for recovery on individuals. SilverCloud is a course that the client takes, where a specialist will check in every week over a chat. And Togetherall is a peer-to-peer site where you talk to other people – as individuals – and your progress is monitored, essentially, by yourself. Like Bartleby, everywhere we turn we are surrounded by walls; walls that cut us off, keep us in our daily cycles and routines, where we all work side-by-side but never really together.

Bartleby’s statement ‘I would prefer not to’ could be a mantra for our own times. It reminds me of the writer Matt Colquhoun, who, working with Fisher’s writing, takes the word ‘egress’ and uses it as a way of conceptualising a way out, a retreat, from the society we find ourselves in. Perhaps the best example of this ‘I prefer not to’ ideology comes with John Lennon’s bed-ins for peace, of the literal desire to do nothing in a society that drives you to do anything and everything, that prizes movement and constant consumption over inertia. It’s the desire, I think, for not only a world that abolishes the pursuit of freeing us from boredom – with our many apps and our commodified side-hustles (like selling our paintings and our hand-made trinkets on Etsy for extra cash, when in actuality our hobbies should be our hobbies) – but also for a world that abolishes our need to work. It’s a way of conceptualising a freedom we never thought we had. We get a job for money to buy the things we need, and, like Bartleby, we might start to realise how dumb it all feels. How fake. What would be the result, really, if we said we preferred not to work till we die, preferred not to pay for our education, preferred not to talk to our doctors over an online chat, preferred not to bail out corrupt bankers, preferred not to take part in this laughable excuse of a society. What if we said we preferred not to be bored of being bored?

With all this in mind, I’m looking forward to listening to One Hour Theatre Company’s innovative contemporary take on Bartleby, to see how this canonical tale has been readapted in a new format, at a time when it has never been more relevant in a world of economic and social alienation.

Part of WoWFest21: celebrating 21 years of radical writing. Check out the full programme here.