New fossil finds from South Africa and Southern China shake up our human family tree

28th October 2015: Dr Isabelle De Groote

The past two months have seen a plethora of new discoveries in the field of human palaeontology that has shaken up our family tree. Not our distant family tree but, instead, this time the news involves members of our own genus, Homo.

First, in early September 2015, came the announcement of the discovery of a new human species from the Dinaledi cave, located 50 km from Johannesburg in South Africa. The bones were recovered from a small dark chamber at the back of the cave by young female archaeologists who squeezed their way through the underground fissures. They extracted around 1500 fossil elements but left what appear to be additional fossil bones in the site for future research. After the excavation, a large international team of paleoanthropologists worked together to extract as much information as possible from the bones. They concluded their analysis by determining that the bones belonged to at least 15 individuals (including infants, children and adults) that, although they are currently undated, belong to a new species of the genus Homo and named it Homo naledi (human star).

The new human may be a direct ancestor of our own species and shows a unique blend of ape and humanlike characters: a small brain but humanlike hands well suited to making tools, for example. How the humans got into the cave is a big enigma that will require more research and hopefully dating analysis will allow the scientists a better understanding the role and position of this new human on our family tree.

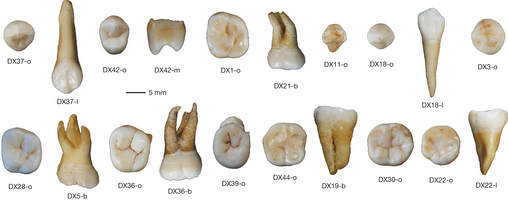

From the other side of the world in southern China (Daoxian) came the news early October 2015 that 47 modern human teeth were discovered that date back to at least 80,000 years ago. The presence of what are clearly modern humans (Homo sapiens) that long ago in southern China means that we need to rethink the dispersal models of our own species. Until now, genetic, archaeological and palaeoanthropological evidence has supported that modern humans evolved in Africa around 200,000 years ago and left Africa around 60,000 years ago to migrate all over the world, replacing the local populations of hominins living there at the time. We are all thought to be descendants of that diaspora.

A few years back DNA evidence made palaeoanthropologists accept the view that human, when they arrived in other parts of the world inbred (on a small scale) with the local populations (e.g. Neanderthals in Europe, Denisovans in Western Asia).

This new research by renowned dental anthropologist Maria Martinon-Torres (UCL) who analysed the Chinese teeth and securely identified them to be those of modern humans, now challenges this accepted out-of-Africa date by at least 20,000 years. The teeth are securely dated by the overlying stalagmite to be at least 80,000 years old and the associated animal fossils also confirm their Late Pleistocene age.

Although we may all still be descendants of the humans that left Africa 60,000 years ago, palaeoanthropologists will need to rethink their distribution models to explain how modern humans ventured all the way into Southern China before 80,000 years ago. One possible explanation is that there were many earlier migrations out of Africa by small groups of humans that didn't survive and we just haven’t found their fossil remains yet.

More paleoanthropological fieldwork and fossil recovery is needed in areas such as Asia and the Middle East to give us a more complete picture of our evolutionary past.