Raising interest rates in periods of increasing financial stress

The European Central Bank doesn’t shy away from raising interest rates amidst financial turbulence. Should the Bank of England follow suit? Professor Costas Milas writes that raising rates is not necessary. He says that the current negative growth in the UK’s divisia money supply and rising financial stress will put downward pressure on prices and suppress GDP growth.

During the recent pandemic we were told, in sharp contrast to the 2008 financial crisis, that banks were part of the solution rather than the problem. Yet, the collapse of Silicon Valley Bank followed by Flagstar Bank stepping in to buy most of the operations of Signature Bank and UBS stepping in to rescue rival Credit Suisse has brought back memories of the 2008 financial crisis.

Does it then make sense to increase interest rates when financial market turbulence is on the rise? The European Central Bank (ECB) appears to think so. Indeed, it raised interest rates in March 2023 by another 0.5 percentage points on the grounds that its main priority is to fight inflation. The ECB also appeared reassured that European banks have strong capital adequacy to withstand a banking crisis, which is also the case for UK banks based on recent “stress tests“. Contrast this with the US, however, where banking regulation appears less strict since 2018, which has arguably made mid-sized banks like Silicon Valley Bank more vulnerable.

Should the Fed and the Bank of England also proceed with further interest rate hikes to fight stubbornly high inflation? The broader question, of course, is whether central banks should raise interest rates in the presence of elevated financial market stress.

Whatever the answer to these questions might be, one thing seems certain to me. The economic profession has learnt some lessons since the 2008 financial crisis. Indeed, the financial crisis of 2008 triggered a lively debate among policymakers and the economic profession on what went wrong with their forecasting ability. For instance, the president of the Federal Reserve Bank of Boston, Eric Rosengren, noted in 2010 that the crisis was underestimated because financial links to the real economy were “only crudely incorporated into most macroeconomic modelling”. Also the head of the Monetary and Economic Department at the Bank of International Settlements, Claudio Borio, noted in 2012 that “financial factors in general progressively disappeared from macroeconomists’ radar screen” for most of the post-war period.

Financial economists and policymakers took seriously into account the above comments. For instance, Bank of England staff make the point that the bank’s forecasting platform has incorporated quantitative easing policies in the bank’s empirical models. Colleagues and I showed that an empirical model, which distinguishes between illiquid and liquid stock market conditions in the UK, is able to out-perform the GDP growth forecasts produced by the bank’s Monetary Policy Committee (MPC). In addition, colleagues and I showed that rising financial stress suppresses UK GDP growth for up to 20 months but also reduces divisia M4 money supply in the economy (note: divisia money weights component assets of money in accordance with their usefulness in making transactions). Divisia M4 money growth in the UK economy has turned negative for the first time since the 2008 financial crisis. So, one has to question whether further interest rates are necessary. This is because the reduction in divisia money, which started before the financial turbulence of the last few days, will definitely put downward pressure on UK inflation, in addition to suppressing UK GDP growth. Add to this academic research by ECB staff members showing that an unexpected worsening of conditions in financial markets causes a decline both in output and prices, and we conclude that further interest rate rises, for the time being, are not necessary!

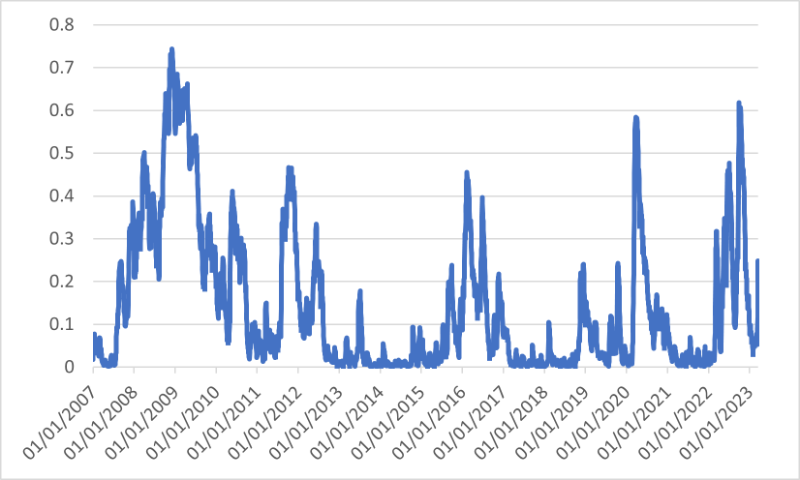

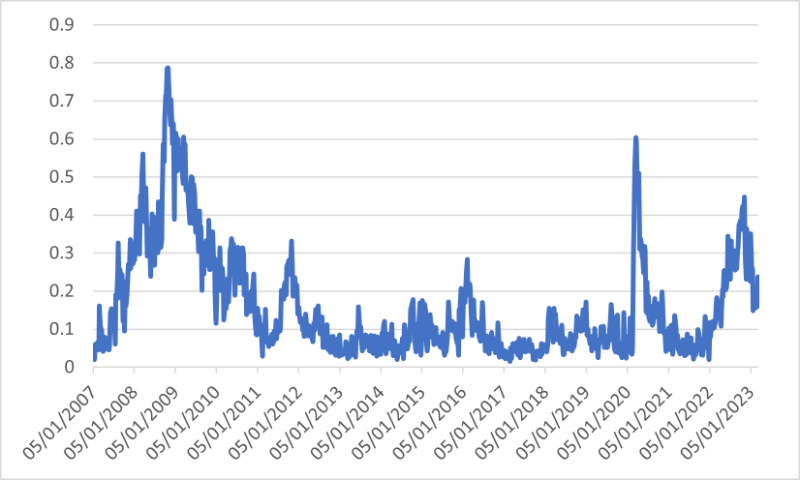

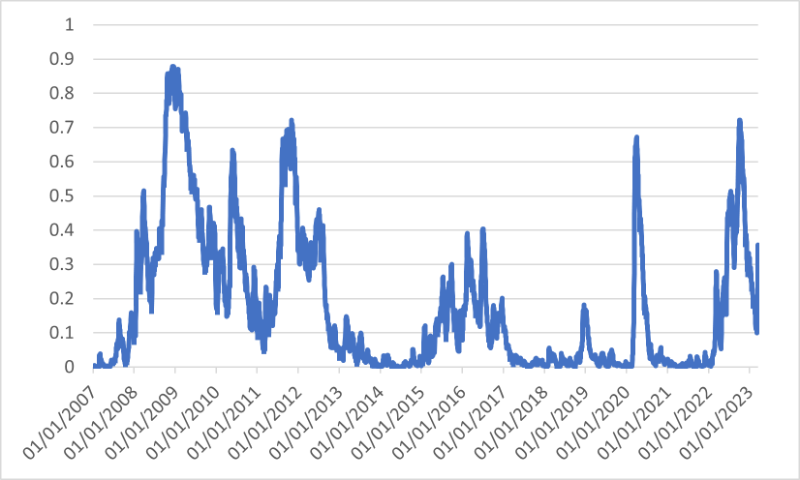

Let us have a look at current financial stress indicators in more detail. The ECB compiles such indicators for Eurozone countries, the US, and the UK. These indicators include market-based financial stress measures that are split equally into five categories, namely the financial intermediaries sector, money markets, equity markets, bond markets and foreign exchange markets. In light of the failure of Silicon Valley Bank and the difficulties Credit Suisse is currently facing, among others, financial stress measures in the US, the UK, and Germany are elevated (see Figures 1 to 3).

Figure 1. Financial stress – UK

Source: ECB Eurosystem

Figure 2. Financial stress – US

Source: ECB Eurosystem

Figure 3. Financial stress – Germany

Source: ECB Eurosystem

These measures, however, do not indicate any substantial stress relatively to what we observed during the financial crisis in 2008. In the case of the UK, current financial stress is much milder than during 2016 EU Referendum or following the so called “mini-Budget” of the Liz Truss premiership in September 2022.

However, these financial stress measures (should) provide hints on the interest rate setting behaviour of Central Banks. Back in 2010, for instance, Prof Chris Martin and I showed that the Bank of England’s Monetary Policy Committee raises interest rates when inflation exceeds the 2% target and output exceeds potential (or ‘trend’) output, but lowers interest rates when financial stress is on the rise.

Currently, the Bank of England expects UK inflation to drop from nearly 10% to 3% by early 2024. Recent movements in the Global Supply Chain Pressure Index, which predicts inflation movements quite well, indicate that inflation pressures are receding. The Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) estimates that output was above potential in the last quarter of 2022; however, it will drop below potential during the first quarter of 2023.

I have just re-estimated a ‘monetary policy rule’ which sets interest rates based on the above “drivers” of interest rates (that is, inflation relative to the target, output relative to potential and financial stress, respectively). I find that a temporary pause in UK interest rates (at 4%) is ‘advisable’.

This, however, does not necessarily mean that UK interest rates will not rise. The Bank of England has just published its latest survey on public expectations of inflation. According to the survey, the public expects inflation to persist at 3% two years into the future in sharp contrast to the Bank of England, which expects inflation close to 1% in 2025! It is reasonable to assume that high public expectations of inflation will translate into persistent demand for higher, than otherwise, wage increases which, in turn, will lead to higher, than otherwise, interest rates. In other words, a pause in interest rate rises is far from guaranteed! The counterargument to this is that a 3% inflation two years down the road is “acceptable”, considering the very high inflation we have witnessed over the last year or so!

This article is republished from blogs.lse.ac.uk. Read the original article here.