History, memory and power – reflections on slavery and emancipating the mind

by Mart Kurismaa, Nagoya University

How do we conceptualise slavery? Why even study it to begin with? Answers to these questions are bound to reflect differences in attitudes and backgrounds, and mine do not constitute an exception. Attending the RENKEI PAX workshop in Liverpool on the topic of slavery, however, gave me a chance to contemplate answers from a philosophical perspective on memory, history, and power. I would thus like to offer my answers from this angle.

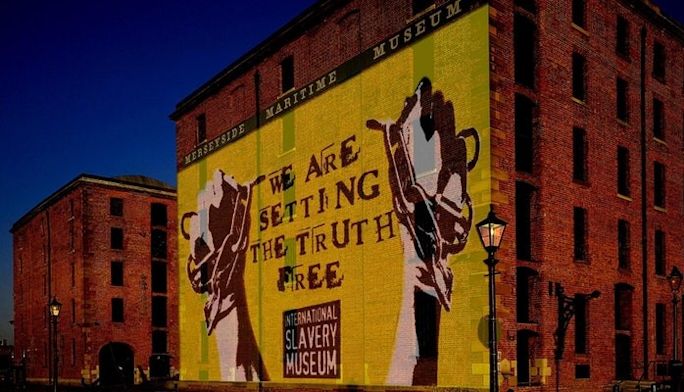

Image: The International Slavery Museum via National Museums Liverpool

In popular understanding, slavery is a relationship between people where one party owns the other as property, exercising absolute power over the latter's life, fortune, and liberty. This, almost verbatim, is also how slavery has been defined legally, wherein it denotes a 'civil relationship' of such character. By today's standards, of course, as opposed to being 'civil' in any sense, slavery is quintessentially criminal. This shift in perception was initially brought about by the abolitionist movement, and then gradually established the moral prerogative of humanity and justice over greed and tyranny, according to the popular narrative. Both the legal and the popular view, thus, portray the issue in starkly black-and-white colour. Repugnant as slavery may have been, its condemnation is forthright, and its significance safely consigned to history.

While there is truth to this image of slavery, it may conceal more than reveal, as is often the case when power and history are confined to moral parables. A brief look at two other examples can illustrate what I mean. Domestically the founding fathers of the United States are widely associated with democratic ideals, which however conceals not just the controversy of their own personal slave ownership, but also their colonial policy that can only be described as genocidal.1 As a second example, use of nuclear weapons against Japanese civilians in 1945 is widely regarded as responsible for Japanese surrender, even though later historical research has left no doubt the surrender had little to do with it (and everything to do with Stalin). In both cases – a genocidal democracy, and a futile nuclear massacre – historical evidence weighs against the more morally or emotionally appealing narrative. The result is an unstable mixture between actual history, its collective memory, and emotional appropriation of the two.

What does this have to do with slavery, or its research? Apparently, a similar disjuncture between history and memory prevails here — and a similar role for emotion in melding the two. One of the most famous slavery memorials, The House of Slaves in Senegal, was never an important slave site, whereas the actual hub of transatlantic slave trade in present day Angola is marked essentially with silence.2 There are political reasons why this is so. Nevertheless, this is not to deny the emotional significance the former site offers to visitors (including Pope John Paul II, Nelson Mandela, and Barack Obama), and the latter does not.

Again, however, a highly selective impression of history is at work. In fact, the identification of slavery with the transatlantic slave trade does not even begin to do justice to intra-African slavery, much less to slavery as a globally pervasive phenomenon, past and present. To a considerable extent, we can conclude, European colonial perpetration of slavery has defined how we understand the concept today, not just legally and popularly, but also in terms of the commemoration it receives.

As I said in the beginning of this essay, my perspective is philosophical. If I find the transatlantic commemoration of slavery partial, and the popular narrative emotional, then what is my own contribution to the debate? Am I saying that slavery research is sensationalist, or meaningless? No: quite the opposite.

My answer revolves around the concept of power, and in fact builds on arguments already introduced. As Jonathan Heaney has argued, emotion and power are conceptual twins marking ever-present, fundamental features of human experience.3 If this is right, then intermediating between history and memory is not just emotion, as pointed out, but indeed power. Power, on this understanding, is not a zero-sum game, and emotion not some hysterical opposite of reason. Both concepts, while apparently simple, lead to profound conclusions that science has just begun to address. While their interrelationship is complex, both power and emotion are constitutive of our identity, our relationships, indeed our reality.

Seen in this light, research into slavery is needed precisely for the reasons I used to critique it — its moral, emotional, partial nature. Rather than dismissal, however, this should serve as impetus to further study. Topics that evoke emotions can do so for reasons that are quite literally powerful, and this alone should justify their study. But when these topics cross paths with actual power to define, determine and structure our reality, then research becomes crucial.

As George Orwell figuratively reminded us: who controls the past controls the future, and who controls the present controls the past. In this sense, history, memory and power can verily be used to enslave the mind — as well as to emancipate it.

References:

1 On genocidal democracies in the New World, see the chapter by the same name in Mann, Michael (2004) The Dark Side of Democracy: Explaining Ethnic Cleansing. New York: Cambridge University Press

2 On the controversies surrounding slavery commemoration, in Africa and elsewhere, see Aruja, Ana Lucia (2014) Shadows of the Slave Past: Memory, Heritage, and Slavery. New York & London: Routledge

3 The argument, as well as brief literature review, is presented in Heaney, Jonathan (2011) 'Emotions and Power: Reconciling Conceptual Twins'. Journal of Political Power 4 (2): 259–77