Colonial Plunder: The Benin Bronzes and the Complexity of Repatriation

Posted on: 25 May 2023 by Aisha Taylor Durán in Posts

Almost 130 years have passed since the looting of Benin City, and yet most of the bronzes remain in the collections of the some of the Western world’s most influential curatorial institutions. MA Student, Aisha Taylor Durán introduces us to the history and arguments surrounding the Benin Bronzes.

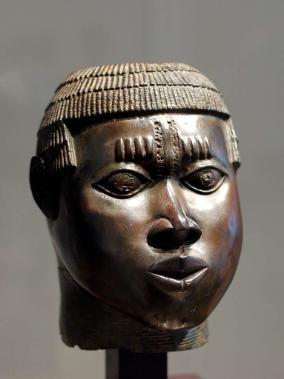

The year is 1897 and a British military force, 1200 men strong, has just entered Benin City, the epicentre of the Edo Kingdom of Benin (now Edo State, Nigeria) and home to the Oba’s (king) Royal Palace. Immediately upon arrival, the force begins to sack the city, burning its buildings and capturing its inhabitants before turning its attention to the Royal Palace. Precious works of art that had been collected over centuries are ripped from walls and snatched from altars before being packaged up and sent to London where the vast majority are sold off in auctions to various private and public collections. Among these works of art are the “Benin Bronzes”, a vast collection of sculptures including commemorative heads, figurines and 900 brass plaques which are now amongst the most contested artefacts in the world.

Almost 200 years have passed since the looting of Benin City, and yet most of the bronzes remain in the collections of the some of the Western world’s most influential curatorial institutions, such as the British Museum and the Smithsonian. Debates over the rightful owners of the bronzes and demands for their repatriation materialised almost immediately after their looting before gaining steady traction in the 1930s. But if the bronzes were clearly acquired under such problematic circumstances, why have museums resisted repatriating them? And is repatriation of the bronzes back to Nigeria even the most effective way to begin making amendments for the wrongs of the past or is the situation more complicated than we give it credit?

When the bronzes were initially seized by the punitive military force, those who took them home to display on their mantlepieces as well the museums who purchased them defended their ownership on the grounds of “spoils of war”. A nineteenth-century law originating from the Roman concept of wartime restitution, it was deployed by colonial powers to acquire and sequester artefacts. But as was the nature of colonial rule, the “spoils of war” law was applied in an inherently paradoxical way to extract precious goods from colonised countries.

When first conceived by the Romans, the law was used to legitimise the victor’s right to take the property of the vanquished who by losing, lost all right to property. However, by the nineteenth-century the law was altered to favour the loser, stating that should their property be seized unjustly, it had to be returned. When Napoleon looted artworks from across Europe during the late eighteenth-century, the law was utilised by the allied powers during the Second World War to claim back thousands of stolen pieces from institutions such as the Louvre. But in the case of colonised countries, Salome Kiwara-Wilson explains that ‘restitution customs in international law did not apply to the Benin case/ due to 19th century racism’. As a subject of the British Crown, the former Benin Kingdom was denied the privilege of being treated as equal under the law, thus allowing for the Benin Bronzes to remain separated from their homeland.

Nowadays, however, rarely do you hear “spoils of war” being directly invoked when it comes to the defence of keeping the Benin Bronzes in Western museums. Instead, a number of new objections have been raised. Such objections range from the safety of the artefacts to the educational benefit of museums being able to display them. But perhaps the most controversial one is the idea that, since those responsible for the plundering of the bronzes are no longer alive, why is it the moral responsibility of their actions extended to their (broadly speaking) descendants?

A succinct response to this argument is made by Tiffany Jenkins who states that:

By presenting the people of today as casualties of the past, the move towards reparations implicitly detaches responsibility for action in the present. By encouraging people to blame the past for today’s troubles, rather than face up to the problems of today and the future, the all-important relationship between action and accountably becomes eroded.

Nonetheless, despite the reluctance museums have and continue to display when it comes to repatriating the Benin Bronzes, advancements have been made. In November 2021, the Musée de quai Branly returned 26 of its bronzes whilst in November of the following year the Horniman Museum agreed to return their entire collection of 72 Benin Bronzes after a request was made by Nigeria’s National Commission for Museums and Monuments (NCMM). Further progress was made when in December last year, Germany returned 21 bronzes from various museums. The return of these bronzes out of the 5000 that are scattered across the globe represent small, but necessary steps to begin addressing the harm caused by colonialism.

However, it is important to frame these acts of repatriation within a larger context. Unsurprisingly, The British Museum still holds the largest collection of Benin Bronzes in the world and as noted by Philip Oltermann, ‘whose governments have stonewalled restitution debates for more than a century’. The British Museum website states that it ‘has positive relationships with the royal palace in Benin City and with the NCMM’ and is a member of the Benin dialogue group. Yet, there is little to show for these discussions and “positive relationships.” One also cannot help thinking that the museum’s role in deciding the future of the bronzes, no matter how pragmatic or necessary, carries undertones of colonial paternalism.

It must also be noted that many major museums that currently house collections of the bronzes insist on temporary loans as opposed to permanent ones. In 2018, the major museums who are part of the Benin dialogue group announced that they would loan their bronzes to the planned Edo Museum of West African Art. Whilst negotiations did involve representatives from Nigeria, it was nonetheless criticised due to the unwillingness of the member museums to transfer ownership to the Edo Museum. Christian Kopp, the co-founder of Berlin Postkolonial, argued that the plan was an example of ‘shameful power politics’ and that ‘it is us Europeans who should ask for loans’ of repatriated artefacts. On this topic, the historian Dan Hicks has concluded that ‘museums reduce ‘decolonisation’ to ‘art washing’ by offering long-term loans rather than giving back what was stolen.

Up until this point in this article, it would seem that in an ideal world, all the bronzes would be repatriated back to Nigeria. But what of the children of the African diaspora, who, due to the enforced migration of their enslaved ancestors, now exist across the globe. Do they have a legitimate claim to the bronzes? A group of African Americans would argue yes.

When the Smithsonian announced that it would be transferring ownership of some of its bronzes back to Nigeria, an unexpected turn of events occurred amidst the celebrations. The Restitution Study Group (RSG), described as a ‘non-profit concerned with slavery justice’ filed a lawsuit against the Smithsonian in an effort to stop the transferal. The lawsuit was based on the argument, explains Adaobi Tricia Nwaubani, that the bronzes ‘are also part of the heritage of descendants of slaves in America, and that returning them would deny them the opportunity to experience their culture and history.’

Over 100,000 enslaved people were taken from Nigeria and transported to the United States during the Trans-Atlantic slave trade, resulting in millions of their descendants now living across the country. The response to the lawsuit has been divisive to say the least. Nwaubani noted that most of the Nigerians with whom she discussed the lawsuit with simply ‘burst into laughter’. Others such as David Edebiri, a member of the cabinet of the current Oba, expressed a more sympathetic view, acknowledging that ‘the artefacts are not for the Oba alone. They are for all Benin people, whether you are in Benin or not.’ Nonetheless, whilst Edebiri’s statement may recognise that the bronzes are now part of wider cultural heritage, that does not mean to say that they belong in the US nor any other country where the diaspora is located. Regardless of how legitimate you may think the claim of the RSG and those in accordance with their stance is, the lawsuit has a generated a new area of discourse around repatriation and highlights the cultural and social complexity surrounding the topic.

So where do we go from here? What may have been the easy answer to that question has now become infinitely more intricate. Nonetheless, the battle for the repatriation of the Benin bronzes, or any other colonial artefacts, should not be dismissed simply for the inevitable challenges that will be encountered. The fate of the bronzes is significant not only for Nigeria but for the continent of Africa, where an estimated 90% of its cultural heritage resides outside of its borders. The vast majority of these artefacts were stolen or acquired under dubious legal circumstances. To add insult to injury, many of these artefacts are not on display but rather sequestered in museum archives, some lacking any kind of record or classification. By refusing to repatriate artefacts museums ultimately replicate the same colonial violence that resulted in their acquisition in the first place.

Repatriation must ultimately begin with the acceptance that these artefacts were not lawfully acquired and the dismantling of the notion that only Western museums are up to the task of protecting them. But fundamentally, discussions around repatriation should not centre non-Africans but rather Africans themselves as well as the diaspora for it is they who should be the deciders of the fates and legacies of their cultural heritage.

Keywords: Repatriation, Benin Bronzes, Blog, Article .