The art of the Prehistoric Aegean

Dr David Smith is a Continuing Education lecturer and Researcher at the University of Liverpool. Dr Smith has written extensively on Ancient Greece and his book Pocket Museum: Ancient Greece is available to download.

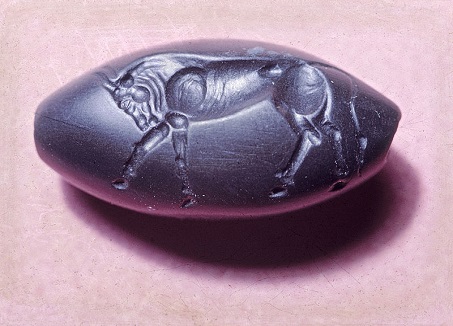

Turned up by the plough or recovered by idle goatherds driving their flocks across the countryside, the small, semi-precious, sealstones once used by Minoan elites on the Mediterranean island of Crete to express identity or denote property ownership, were, by the 19th century, shrouded in folkloric superstition and imbued with magical or talismanic properties by rural populations; a common fate for ancient artefacts. Highly valued by young Cretan women, they were known as galopetras, or ‘milk-stones’, and when strung at the neck or breast were thought to guarantee the milk of nursing mothers; a very real concern at a time when the health of mothers and their babies were regularly at risk. Pale stones, most milk-like in their hue, were prized above all others.

By the end of the century, a handful of such stones had appeared in private European collections, and they had become an increasingly common sight among the stock of antiquities dealers plying their trade below the Athenian Acropolis at the famous Shoe Lane flea market; a go-to haunt for both collectors and early Greek archaeologists alike. It was an Athenian-bought stone which found its way to the Ashmolean Museum at Oxford in early Mi1889, and which immediately piqued the interest of its then Keeper, Arthur Evans.

The unusual pictographs which adorned this stone were cautiously identified by Evans as elements of a prehistoric writing system. As a former correspondent for the Manchester Guardian covering the Balkan insurgency against Ottoman rule, he was no stranger to foreign travel (or political unrest) and would soon make his way to Crete, then also under Ottoman rule, in search of other examples to support his theory. Making door-to-door enquiries in villages across the centre and east of the island, Evans was able to buy stones from women past child-bearing age, and to take impressions of those he could not secure; others were bought from dealers in the island’s capital or recovered by Evans himself during visits to known prehistoric sites. His early work with sealstones resulted in the identification of two prehistoric scripts: so-called Cretan Hieroglyphic and Linear A; both, still, undeciphered. Perhaps more importantly, it enabled him to familiarise himself with the site of Knossos, the Bronze Age palace of the legendary king Minos (and home of the mythical minotaur), the excavation of which would later cement his name as the principal architect of Minoan archaeology.

Those sealstones today housed in the Garstang Museum of Archaeology were donated by three of the university’s teaching staff. Two were contemporaries of Evans: Robert Carr Bosanquet, Director of the British School of Archaeology at Athens (BSA) as Evans first broke ground at Knossos, and the leader of excavations at the Minoan sites of Palaikastro (1902-1905) and Praisos (1901-1902), and John Percival Droop, a student of the BSA and a veteran of excavations at Palaikastro and Phylakopi on the Cycladic island of Melos. The third, Richard Wyatt Hutchinson was curator of Knossos before and after the Second World War, during which the site served first as a refuge for locals fleeing fighting and later as a British military hospital, before becoming home to the commander of the German occupation of Crete.

The collection includes a huge range of types, carved by prehistoric lapidaries from a variety of semi-precious stones and decorated with images of animals, plants, abstract patterns and hieroglyphic symbols, ranging in date from their earliest use on Crete to their adaptation into the sealing systems of the Mycenaean world (ca. 2750-1200 BCE).

Dr Smith will be teaching a Continuing Education course Art in the Prehistoric Aegean from Wednesday 24 April for 5 weeks – for more information click here.