Research

Molecular Constraints on Convergent Evolution

Understanding when evolution produces predictable outcomes is a central challenge in biology, with implications for biodiversity, health, and environmental change. Convergent evolution provides a powerful framework for examining molecular architecture, physiological trade-offs, and ecological context that constrain the range of viable adaptive solutions. Our research uses toxin resistance and chemical defence as model systems to identify the principles that govern adaptive evolution across biological systems.

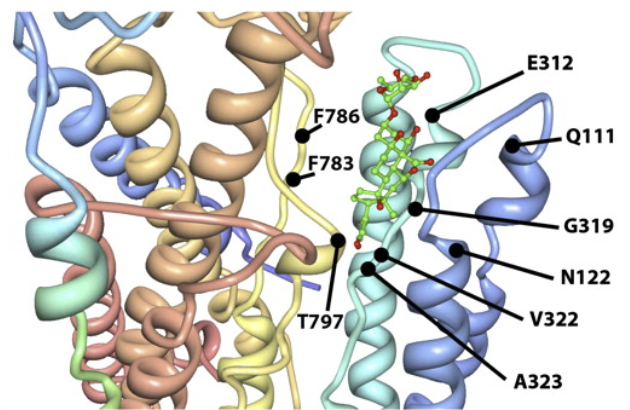

We focus on cardiotonic steroids, a class of bioactive plant compounds that target the Na⁺/K⁺-ATPase, an essential and highly conserved enzyme with relevance to physiology, pharmacology, and disease. Across insects and vertebrates, resistance to these compounds has evolved repeatedly, often via a limited set of recurrent amino-acid substitutions. This makes cardiotonic steroid resistance an ideal system for studying how molecular constraints shape evolutionary trajectories, limit alternative solutions, and generate predictable outcomes.

Using chemically defended insects and specialised predators as tractable experimental models, we integrate ecological interactions, organismal physiology, and molecular analyses to examine how variation in toxin exposure influences performance, fitness, and survival. At the molecular level, we analyse Na⁺/K⁺-ATPase gene families and functionally characterise resistance-conferring mutations, generating insights relevant to protein function, robustness, and evolutionary constraint.

By linking molecular mechanisms with ecological and evolutionary dynamics, our work provides a foundation for understanding how organisms respond to bioactive compounds, environmental stressors, and selective pressures. This mechanistic framework is directly relevant to broader questions in evolutionary medicine, pharmacology, and systems biology, and is readily integrated into collaborative, interdisciplinary research programmes.

Chemical Defence, Signalling, and Sensory Ecology

Our research investigates how chemical defences and visual signals are perceived by predators, and how these perceptions shape the evolution and diversification of warning colouration and behaviour. In collaboration with the Max Planck Society and the University of Costa Rica, we study Costa Rican poison frogs that vary naturally in colour, toxicity, and behaviour, examining how visual signals, behavioural strategies, and the sequestration of dietary toxins interact to influence predator responses under natural ecological conditions.

Complementary experiments with naïve domestic chicks provide mechanistic insight into predator perception, revealing innate biases such as avoidance of red stimuli, preferences for prey shape, and neural responses to taste cues.

In parallel, through collaborative work funded by the Australian Research Council, we investigate geographic and temporal variation in warning colouration and chemical defence in the tiger moth Amata nigriceps across eastern Australia. By comparing populations that differ in climate and predator community structure, we quantify how environmental context and predator pressure shape the expression, reliability, and maintenance of warning signals across space and time. Together, these approaches link ecological variation with behavioural and sensory mechanisms to explain how predator cognition drives the evolution and persistence of chemical defence and signalling systems.

Sensory Integration and Adaptive Responses

My research investigates how organisms sense, integrate, and respond to environmental information, and how these processes generate adaptive behaviour and evolutionary change. A central aim is to understand how coordinated responses emerge across biological systems, from local tissue-level processes to whole-organism behaviour, without relying exclusively on centralised neural control.

In collaborative work on camouflage and masquerade, we examine how prey reduce detection by predators and how predator decision-making shapes the evolution of these strategies. This research integrates behavioural ecology with models of optimal decision-making to understand how sensory cues and environmental context influence attack outcomes.

A complementary research strand focuses on phenotypic plasticity in organisms capable of reversible colour change. Using insect systems as tractable models, we study how environmental information is detected and translated into precise, adaptive phenotypic responses, revealing distributed modes of sensory integration across the body.

Together, this work addresses fundamental questions about information processing, coordination, and adaptation in living systems, providing insights relevant to systems biology, organismal resilience, and interdisciplinary approaches to sensing and response.

Research collaborations

Dr Shabnam Mohammadi

Molecular Constraints on Convergent Evolution

Max Planck Institute for Chemical Ecology

Molecular Constraints on Convergent Evolution

Prof. Pat Eyers

Institute of Systems, Molecular & Integrative Biology

Molecular Constraints on Convergent Evolution

Prof. Dan Rigden

Institute of Systems, Molecular & Integrative Biology

Molecular Constraints on Convergent Evolution

Prof. Dr. Martin Kaltenpoth

Max Planck Institute for Chemical Ecology

Chemical Defence, Signalling, and Sensory Ecology

Prof. Dr. Mariella Herberstein

Leibniz Institute for the Analysis of Biodiversity Change

Chemical Defence, Signalling, and Sensory Ecology

Prof. Ilik Saccheri

Institute of Infection, Veterinary, and Ecological Sciences

Developmental Plasticity in Adaptive Colouration