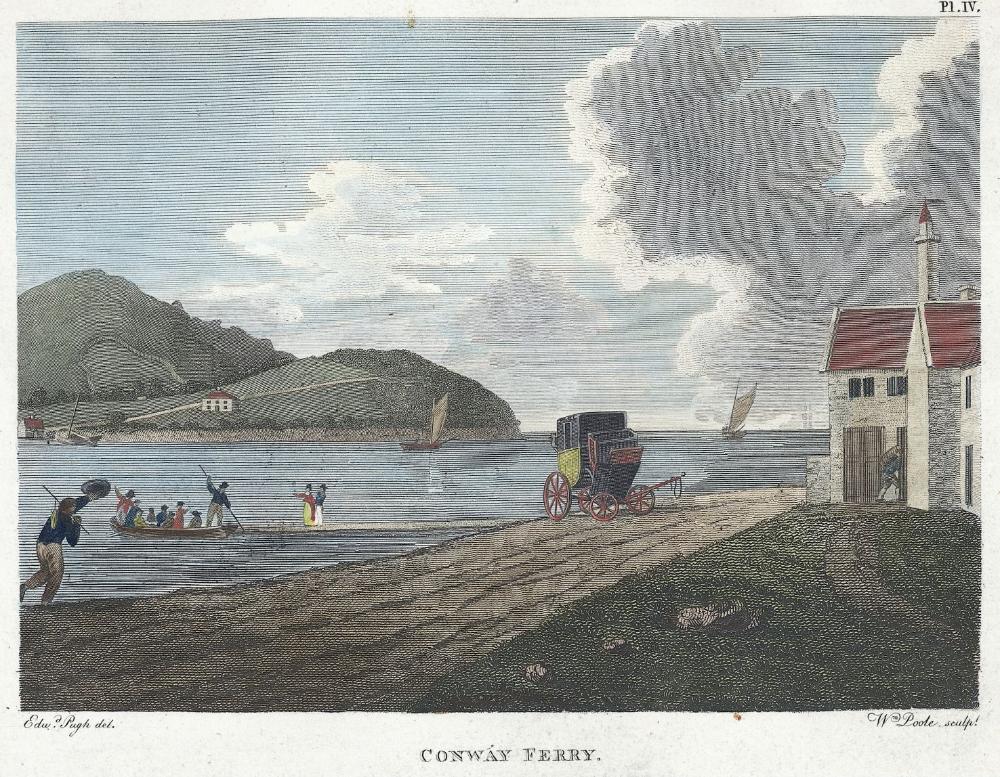

A print of Conwy Ferry in 1795:

Another image, from a painting by J W Harding in 1810.

There is a claim circulating that on three occasions a ferry boat crossing the Menai was lost with only one survivor - named Hugh Williams and each time on the same date of 5 December. This would be a huge coincidence - and the facts, as related below, suggest some elements of this story are correct - but not all. Two of the disasters did result with only one survivor, named Hugh Williams, [1785 and 1820], but the dates were different. The 1842 disaster also had only one survivor: though named Richard Thomas. A, much later, report of the 1664 disaster states that there was only one survivor in that case also.

Ferry disasters

1664 79 lost, Abermenai, 1 saved, date unknown;

1723 30 lost, Tal y Foel, 2 saved, 13 April;

1726 ?? lost, Bangor, 2 saved, date unknown;

1785 54 lost, Abermenai, 1 saved [Hugh Williams], date 5 December;

1820 21-25 lost, near Caernarfon, 1 saved [Hugh Williams], date 5 August;

1842 14 lost, Lavan Sands, 1 saved [Richard Thomas], date 30 May.

1785, 1787, 1797 private record of ferry losses.

Ferry disasters at other ferry crossings in North Wales:

Conwy Ferry disaster 1806 11-15 lost, 2

saved, 25 December.

Dee Estuary

Ferry disasters.

See also Mersey Ferry disasters.

Reports, quoted in book "North Wales ... delineated from two excursions in summers 1798 and 1801,,.." by Rev. William Bingley, of ferry services and ferry disasters in the Menai Straits, linking the mainland with Anglesey. [I have found no confirmation of the reports of the 1664, 1723 and 1726 disasters].

There are six ferries from Caernarvonshire into Anglesea; Abermenai, about three miles south-west of Caernarvon; Tal y Voel, from Caernarvon; Moel y Don, about half way betwixt Caernarvon and Bangor Ferry; Porthaethwy, or Bangor Ferry; that from the promontory of Garth, near the town of Bangor; and from Aber, across the Lavan Sands to Beaumaris. - Several accidents have at different times happened at these ferries.

1664. The Abermenai ferry-boat (which is sometimes brought to take passengers from Caernarvon to the Abermenai house, in Anglesea), had arrived at the Anglesea shore from Caernarvon, the oars were laid aside, and the passengers were about to land, when a misunderstanding occurred concerning a penny more than the people were willing to pay. During the dispute the boat was carried into a deep place, where it upset, and although it was at that time within a few yards of the shore, seventy-nine of the passengers perished, one only escaping:- The country people believed that this was a visitation of heaven, because the boat was built of timber that had been stolen from Llanddwyn abbey.

1723. The Tal y Voel boat was upset on the thirteenth of April, and thirty persons perished. A man and a boy only escaped, the former by floating on the keel of the boat, and the other by laying hold of the tail of one of the horses, was dragged to the shore.

1726. The Bangor ferry-boat was so overloaded with people in their return from Bangor fair, that it sunk, and all the passengers (the number not known) were drowned, except one man and a woman. The latter floated on her clothes till she was taken up by another boat. She was alive in the year 1798.

Report, quoted in book by Rev. William Bingley, touring North Wales 1798-1801, from the sole survivor, Mr. Hugh Williams, a respectable farmer now living at Tyn Llwydan, near Aberffraw, in Anglesea.

The Abermenai ferry-boat usually leaves Caernarvon on the return of the tide, but the 5th of December being the fair-day, and there being much difficulty, on that account, in collecting the passengers, the boat did not leave Caernarvon that evening till near four o'clock, though it was low water at five, and the wind, which blew strong from south-east, was right upon our larboard bow. It was necessary that the boat should be kept in pretty close to the Caernarvonshire side, not only that we might have the benefit of the channel, which runs near the shore, but also that we might be sheltered from this wind, which blew directly towards two sand-banks, at that time divided by a channel, called Traethau Gwylltion, The shifting Sands. These lay somewhat more than half way betwixt the Caernarvonshire and the Anglesea coasts. --It was not long before I perceived that the boat was not kept sufficiently in the channel, and I immediately communicated to a friend [Thomas Coledock, gardener to O. P. Meyrick, Esq. of Bodorgan], who was along with me, my apprehensions that we were approaching too near the bank. He agreed in my opinion, and we accordingly requested the ferry-men to use their best efforts to keep her off. Every possible exertion was made to this purpose, with the oars, for we had no sail, but without effect, for we soon after grounded upon the bank; and the wind blew at this time so fresh as at intervals to throw the spray entirely over us.Alarmed at our situation, as it was nearly low water, and as there was every prospect, without the utmost exertion, of being left on the bank, some of the tallest and strongest of the passengers leapt into the water, and, with their joint force, endeavoured to thrust the boat off. This, however, was to no purpose, for every time they moved her from the spot, she was with violence driven back. --In this distressing situation the boat half filled with water, and a heavy sea breaking over us, we thought it best to quit her, and remain on the bank in hopes, before the rising again of the tide, that we should receive some assistance from Caernarvon. We accordingly did so, and almost the moment after we had quitted her, she filled with water, and swamped. - Before I left her, I had however the precaution to secure the mast, on which, in case of necessity, I was resolved to attempt my escape: this I carried to a part of the bank nearest to the Anglesea shore, where I observed my friend with one of the oars, which he had also secured for a similar purpose.

We were at this time, including men, women, and children, fifty-five in number, in a situation that can much better be conceived than described. Exposed, on a quick-sand, in a dark cold night, to all the horrors of a premature death, which, without assistance from Caernarvon, we knew must be certain on the return of the tide, our only remaining hope was that we could make our distress known there. We accordingly united our voices in repeated cries for assistance, and we were heard. The alarm bell was rung, and, tempestuous as the night was, several boats, amongst which was that belonging to the custom-house, put off to our assistance. We now entertained hopes that we should shortly be rescued from the impending danger; --but how were we sunk in despair when we found that not one of them, on discovering our situation, dared to approach us, lest a similar fate should also involve them. A sloop from Barmouth, lying at Porth Leidiog, had likewise slipt her cable to drop down to our assistance, the only effectual relief we could have received; --but before she floated the scene was closed.

Finding that our danger was now every moment increasing, and that no hopes of help whatever could be entertained, I determined to continue no longer on the bank, but to trust myself to the mercy of the sea. Being a tolerably good swimmer, I had full confidence that, with the mast, I should be able to gain the Anglesea shore. I accordingly went to the spot where I had deposited it, and found my friend there, with the oar in his hand. I proposed to him that we should tie the mast and oar together with two straw ropes, which he also had along with him, and endeavoured to persuade him to trust ourselves upon them. I fastened them together as securely as possible, and finding, after repeated endeavours to prevail on him to accompany me, that he had not fortitude enough to do it, I was determined to make the effort alone. I pulled off my boots and great coat, as likely to impede me in swimming: he committed his watch to my care, and we took a last farewell. I pushed the raft a little off the bank, and placed myself upon it, but at that moment it turned round, and threw me underneath. --In this position, with one of my arms slung through the rope, and exerting all my endeavours to keep my head above water, overwhelmed at intervals with the spray which was blown over me with great violence, I was carried entirely off the bank. When I had been in the water, as near as I could recollect, about an hour, I perceived, at a considerable distance, a light. This I believed to be (as it afterwards proved), in Tal y Voel ferry house: my drooping spirits were revived, and I made every exertion to gain the shore, by pushing the raft towards it, at the same time calling out loudly for help. But judge of my disappointment when, in spite of every effort, I was carried past the light, and found myself driving on rapidly before the wind and tide, deprived now of every hope of relief. Dreadful as my situation was, I had, however, still strength enough to persevere in my endeavours to gain the shore. These, after being for some time beaten about by the surge, which several times carried me back into the water, were at length effectual. After having been upwards of two hours tossed about by the sea, in a cold and tempestuous night, supported only by clinging hold of the mast and oar of a small boat, I was thus providentially retrieved from otherwise inevitable death. --- I now felt the dreadful effect of the cold I had endured, for, on endeavouring to rise, that I might seek assistance, my limbs refused their office. Exerting myself to the utmost, I endeavoured to crawl towards the place where I had seen the light, distant at least a mile from me, but at last was obliged to desist, and lie down under a hedge, till my strength was somewhat recovered. The wind and rain soon roused me, and after repeated struggles, and the most painful efforts, I at length reached the Tal y Voel ferry-house. I was first seen by a female of the family, who immediately ran screaming away, under the idea that she had encountered a ghost. The family, however, by this means were roused, and I was taken into the house. They put me into a warm bed, gave me some brandy, and applied heated bricks to my extremities: this treatment had so good an effect, that on the following morning no other unpleasant sensation was left than that of extreme debility. --Having been married but a very short time, I determined to be the welcome messenger to my wife of my own deliverance. I therefore hastened home as early as possible, and had the good fortune to find that the news of the melancholy event had not before reached my dwelling.

This morning presented a spectacle along the shore which I cannot attempt to describe. Several of the bodies had been cast up during the night. The friends of the sufferers crowded the banks, and the agitated inquiries of the relatives after those whose fate was doubtful or unknown, and the affliction of the friends of those already discovered, to this day fill me with horror in the recollection:- I, alas, was the only surviving witness of the melancholy event. - Besides those bodies thrown upon the shore by the tide, so many were found in various positions, sunk in the sand-bank, that it was not till after several tides that they could all be dug out. -- My boots and great coat were found under the sand, nearly in the place where I had left them. The boat was never seen afterwards, and it is supposed to be even yet lodged in the bank.

Newspaper reports:

Hampshire Chronicle - Monday 19 December 1785: [see later version below]

By a letter from Anglesea we have this day received the melancholy

account of between sixty and seventy persons being drowned on Monday

night the 5th instant, about eight clock, crossing the River Menai, in

the Tally Voyle [sic: Tal y Foel] ferry-boat, from the town of

Caernarvon to the Anglesea shore; among the unfortunate number were a

clergyman and his wife, and many very reputable farmers. What made the

scene so very distressing, was, the boat striking on a sand bank, half

the Channel over, which filled her instantly with water, the boat

being so heavy laden with such number of people on board. All the

people then quitted the boat, and went on the sand bank which was at

that time dry. Their cries were soon heard on the Caernarvon and

Anglesea shores. Many boats went to their assistance, but from the

violence of the wind, and the sea running so very high, no relief

could be given them, though repeated trials were made by the boats,

but they dared not approach too near the sands, because if they had

touched them they must have shared the same fate with those

unfortunate people. Only one man was saved out of the whole, and that

man by his being a remarkable good swimmer.

Chester Courant - Tuesday 20 December 1785:

SIR. As your Anglesea Friend has misstated to you some of the

Facts concerning the Misfortune of the 5th, not the 15th, near

Carnarvon, it is proper you and the Public be set right. It happened

to the ferry-boat of Abermaney [sic, Abermenai], not that of Tal y

Voil, and in going up the channel from Carnarvon to Abermaney,

not in crossing the Menai. That the Passengers, doubting the

sobriety and competency of the Ferrymen, took upon themselves the

Management of the Boat, which was unfortunately driven on the Sand-bank.

This I have from the Mouth of the only Survivor, who was saved by

Means of two Pieces of an Oar and Mast, not by Swimming. I wish

he may long survive as he now lies in a very weak State from the

Event, being full two Hours in the Water, according to the best of his

own judgment. As to any other Boat, belonging to the same Ferry, with

50 Passengers, being in the greatest Danger of sharing the same Fate,

the following Evening, there is not a Syllable of Truth in it.

1868 notebook [NLW MS 19078C]:

A large notebook labelled

'Memorandums' containing a list of the persons lost in the Abermenai

ferry boat disaster, 5 December 1785, copied from a list lent to J. H.

Williams[Rev John Hughes Williams, rector of Llangadwaladr] by Mr Thos

Williams, son of Hugh Williams of Tynllwydan [Tyn Llwydan, near

Aberffraw], the only person who escaped alive, and an extract from a

letter in the Chester Chronicle [see above].

More evidence[from The North Wales Chronicle and Advertiser for the Principality,

28th January 1845]:

LONG TIME AGO: The subjoined memoranda of casualties, the memory of

which is kept alive by tradition, are copied from a family Bible, the

property of an ancient perriwig-maker of this city, long since

gathered to his fathers. As a record of old times departed and beings

passed away, the revival may not be without interest:-

Whereas on Monday evening, the 5th of December, 1785, being

Carnarvon fare day, as Abermenai ferry-boat was crossing from Carnarvon

to Anglesey, was lost, with upwards of sixty persons on board, all of

whom were drowned (exept one) that came ashore on the mast. [as reported above]

June 25th, 1787, being Bangor fare day, a boat from Penmon set out

from Aber-cegin [where Port Penrhyn is now] for Penmon, with thirty-two

persons on board, the boat sunk betwixt the Point and the Green Point,

all of whom were drowned, except three that were taken up.

July 9th, 1797, a boat from Beaumares [sic] set out from Mr. Jackson,

Bangor-ferry, about twelve at night for Beaumares, with three persons on

board, which overset opposite Scilly Wen, were all drowned.

Chester Chronicle - Friday 11 August 1820

DREADFUL ACCIDENT. Port Penrhyn, August 8th, 1820. A most distressing

accident happened Saturday morning last: as the Ferry Boat was crossing

over from Anglesea, near Carnarvon, laden with passengers to the number

of twenty-two, the greatest part which, I am informed, were women, by some

accident, one of the passengers fell overboard. and the rest being very

anxious to save their unfortunate companion; too many went over that

side of the boat, which caused her to fill with water, by which means

they were all drowned but one man, who was so fortunate, I believe, to catch hold

of the boat, and held on until another boat came his assistance. I am

informed there only six men in the boat; the remainder, mostly women,

and some children: a number of the bodies have been found, how many I

cannot say.

Another Account. The Boat and persons who were unfortunately lost, crossing from Anglesea to the Carnarvonshire side, Saturday morning last, for Carnarvon Market, I will acquaint you with what I heard from a mariner, who was an eye witness to the sad calamity: at nine o'clock, a.m., twenty-five in number, including, men, women, and children, set off in a small ferry boat, which number was considerably too much for the boat to go safely over with, in the fairest weather; but it then blew a gale of wind, and before the boat was hardly half way across the Menai, it immediately filled with water, and every soul on board perished; excepting Hugh Williams, Bodouirissaf [sic, Bodowyr Isaf], in the county of Anglesea: eight only of the unfortunate sufferers have been found.

Confirmation: There are at least two people buried at the Old Llanidan Church Anglesey who were drowned crossing the Menai Straits. Margaret Edwards and her son Edward both died on 5th August 1820 so it confirms that there was indeed a tragedy on this date.

Note that the Menai suspension bridge was opened in 1826, but ferries from Caernarfon and Beaumaris continued for many years afterwards.

Carnarvon & Denbigh Herald, Saturday, June 4th, 1842:

Awful Loss of Life. FOURTEEN PERSONS DROWNED IN THE MENAI STRAITS.

The facts of the case are as few and simple, as the interest with which they teem will be intense and general, in these maritime localities.

The boat in question was the property of Richard Thomas, sen., of Beaumaris, one of the victims, and it appears that, on the morning of Monday last, at 6 o'clock, it was employed in conveying a number of persons to gather cockles on the Lavan sands, opposite the town, there to be left until 10 o'clock, at which time it was understood the boat would return for them. True to appointment, the boat returned to the sands on the flowing of the tide but, unhappily, there were more candidates for the return passage than it was prudent to attempt at one time to carry back to Beaumaris, under all the circumstances of the case. Nine persons only, had been conveyed from Beaumaris to the opposite sands, by the boat, on the morning of that day; but on its return at least four other persons claimed to be taken back, a request with which it appears to have been imprudent in the two boatmen, Father and Son, to comply, especially as the people were all heavily laden with cockles, which they refused to leave behind them, and there would have been time to return for the second party after the first had been conveyed over to Beaumaris. That the party were too numerous, and too heavily laden, for the size of the boat, may be inferred from the fact that the water reached up to within a plank of the gunwhale, and that the boatmen were very urgent with the passengers to leave the cockles behind them. This however they refused to do, and the party set off, consisting in all of fifteen persons. The boat went for a time almost parallel with the sand banks, in the direction of the swash, in order as it would seem to avoid a chopping sea and when it had got about a hundred yards on its return, a heavy surf began to break upon them, and the boat shipped water, a circumstance which induced the passengers to rush suddenly all to one side, by which means the boat was upset, and all within perished, except the younger of the two boatmen. The accident was observed at Beaumaris, from whence five or six boats immediately put off to the assistance of the perishing creatures struggling with the billows, but, alas! too late to save. All were engulphed, with the exception of Richard Thomas, jun., who saved his life by swimming back to the sands. Thirteen of the bodies have been recovered, most of them in a state of horrible mutilation. The only body known to have been engulphed, and not yet found, is that of one of the two daughters of a passenger named Grace Ishmael, wife of William Ishmael, mariner; the body of the mother and one of her daughters only being restored to the unfortunate and bereaved man. The bodies were conveyed to the White Lion, and to the Shirehall, Beaumaris, there to await the inquest. Close search is being made for the remaining body known to have been drowned, as it is feared, from the unsatisfactory statements of the surviving boatman, as to the exact number of persons he attempted to bring back, that others may have shared in the melancholy catastrophe. The survivor describes himself as having shaken off the unfortunate drowning creatures, with extreme difficulty, owing to their number and pertinacity of grasp. It is to be regretted that he did not at least endeavour to save one of the lesser victims, as he is reported to be a strong and active swimmer, and he had not a long passage back to the sands but danger half extinguishes the lamp of love even in bosoms capable of shrining it.

As the most contradictory reports are in circulation relative to the extent of blame attributed by the jurors, and really attributable, to the deceased boatman and his surviving son, we proceed to lay before our readers an account of the inquest, together with such further particulars, as the coroner and the jurors, in their kindness, could supply.

THE INQUEST. On Tuesday, an inquest was held

on the thirteen bodies that had been recovered from the devouring

element. The inquiry lasted nearly the entire day; and was conducted

before William Jones, Esq Coroner, and a highly intelligent and

respectable jury, consisting of some of the principal inhabitants of

Beaumaris. The following facts appeared in evidence.

Richard Thomas,

son of the deceased owner of the boat, and sole survivor in the

afflicting accident, deposed that he went with his father in his boat

to the Lavan Sands, opposite the town, about 10 o'clock on Monday

morning, to fetch back nine of the deceased, whom he had previously

conveyed there for the purpose uf gathering cockles. That when there,

several other persons got into the boat, besides the nine whom he had

gone for. That the thirteen dead bodies, now shown, are those of the

parties referred to: that, when they had got about a hundred yards off

the sands, the passengers seeing the boat make water, all came on one

side, in consequence of which, the boat upset. That his father, with

all the rest, were drowned and he himself with difficulty, succeeded

in swimming back to the sands. That the boat was not more full of

people than usual. That he was in the habit of carrying as many, and

even more in similar weather. Witness' father had a larger boat; but

it was not used, on this occasion, because it was too large for two

persons to pull over. Nine besides themselves were in the boat when it

went to the sands, but cannot say exactly how many attempted to

return. Is certain that Grace Ishmael had two daughters on board (one

of them not yet found). No caution was given by any one against the

small boat being used. The passengers were told by witness that they

must not delay in returning, as he was fearful of the wind rising.

There was an entire plank between the gunnel of the boat, and the

water, at the time the whole of the passengers were in. Finding that

there was a heavy surf, after getting into the swell, witness wished

the passengers to throw their cockles over-board, but they refused

to do so. He had no ale or spirits that day, before the accident

occurred, His father was also sober. The passengers paid a penny

piece for being taken over.

John Williams, pilot, Beaumaris, deposed

that, whilst bending a trawl at the town's end, his attention was

directed, by William Hughes, to the fact that a boat had capsized near

the Lavan Sands: that they immediately took out a boat, to pick up the

bodies. That, on reaching the spot, they found four floating, and

picked up the two nearest. That by this time other boats had come up,

and witness returned to shore, in company with William Hughes, to

convey to a place of safety the two bodies they had picked up, which,

though apparently dead, were still warm. Witness would not have

ventured out to sea, in so small a boat as that in which the accident

occurred, and with so large a number of passengers, on such a rough

day. Seven or eight would have been quite enough, in such a boat, with

such a swell. Witness was of opinion that, if some of the passengers

had been left on the sands, there would have been sufficient time for

the boat to have returned for them.

William Hughes corroborated the

evidence of the preceding witness.

Anne Owen, wife of Hugh Owen, of

Beaumaris, labourer, deposed that she had wished to cross over to the

Sands early on the morning in question, to gather cockles, but

arrived on the Quay too late, as the boat had gone nearly over. It

then contained the deceased. At its return Richard Thomas refused to

take her over, alleging that it was blowing too much. Witness had

frequently crossed over in that boat, with ten or twelve other

passengers. Did so on Friday last: but it was then a fine day. The

deceased and his son were always very careful.

Ann Thomas, wife of

Evan Thomas, mariner, Beaumaris, deposed as follows: I knew Grace

Ishmael, whose body I now identify also Jane Jones, and the following,

Ann Ishmael, Margaret Owen, Elizabeth Davies, sen., David Hughes,

Richard Thomas, John Hughes, Grace Stanley, Mary Jones, Margaret

Hughes, Owen Jones, and Elizabeth Davies, jun.

This closed the evidence in the case.

After a careful consultation, the jury returned their verdict "drowned accidentally" in each case; with a deodand of £5 upon the boat.

To their verdict the jury attached the following "The jury cannot help expressing their conviction that the accident was mainly to be attributed to the culpable indiscretion of the deceased (Richard Jones) and son, the survivor, in permitting so many persons to get into the boat; which was not, as proved in evidence, capable of conveying so many in rough weather."

The following is a list of the bodies found:-

Grace Ishmael (aged 44), wife of William Ishmael, mariner.

Ann Ishmael (13), her daughter.

Jane Jones, (50), wife of O. Jones, now confined in Beaumaris gaol, convicted for sheep

stealing at the last assizes. She, with her son,

Owen Jones (19), were coming over from Aber to see their father.

Margaret Owen (15), daughter of Richard Owen, of Llanvaes, labourer.

Elizabeth Davies (42), wife of John Davies, labourer, of Beaumaris.

Elizabeth Davies (15), her daughter.

David Hughes (12), son of David Hughes, Beaumaris, labourer,

Richard Thomas (54), the proprietor of the boat.

John Hughes, alias Thompson (16.)

Grace Stanley (12), daughter of Hugh Stanley, slater, Beaumaris.

Mary Jones (27), of Beaumaris.

Margaret Hughes (13), daughter of Hugh Hughes, blacksmith, Beaumaris.

- still missing, another daughter [Elizabeth age 16] of Grace Ishmael.

Before a bridge was built at Conwy in 1826, the ferry (pictured

below; by Edward Pugh in 1795) was the only means of crossing the Conwy

estuary, but was vulnerable to the weather and the strong currents which

swirl along the estuary when the tide is rising or falling. On

Christmas Day 1806, the ferry was transporting the passengers and mail

brought by the Irish Mail coach over the water when it came to grief.

Of the people aboard only two, a rower and a servant were saved. Those

recorded as lost include Richard Edwards [Memorial inscription states

blacksmith from Holyhead, age 36, drowned crossing Conway Ferry 25 Dec

1806], the ferryman, the guard, Mr. Hunt, Mr. Godwin, Mr Elliston and

Mr. Harrison. Some passengers on the mail coach declined to cross on

the ferry - so saving their lives, and the coachman did not cross as he

returned to St. Asaph. Numbers lost, reported by newspapers, vary from

11 to 15.

A print of Conwy Ferry in 1795:

Another image, from a painting

by J W Harding in 1810.

From Kentish Weekly Post or Canterbury Journal - Tuesday 30 December

1806:

We are sorry to state, that on Christmas Day, owing to heavy

swell in the River Conway, the boat conveying the Irish Mail, with eight

passengers, the coachman, guard, and a youth of about 15 years of age,

in all fifteen in number, including the boatmen, was upset, and only two

persons were saved.

Dublin Evening Post - Thursday 01 January 1807:

CONWAY FERRY. In our last paper we mentioned the melancholy account

of the loss of the boat conveying the London Mail the 23d inst. to

Dublin, which occurred in the crossing of that dangerous ferry on the

morning of Thurfday the 25th instant, at ten o'clock A.M. in the sight

of many persons both on the opposite shores of Cheshire[sic] and

Caernarvon, of whom, from the stormy winds and heaving sea, could

administer the least relief to their unhappy fellow-creatures, who

perished in their presence.

Out of fourteen who embarked in the boat, only two have been saved,

from whom material information has transpired: the mails have been

recovered, but the way-bill, containing the names of the passengers in

the mail coach, has not come to hand; the guard of the mail was drowned;

the coachman who drives from St. Asaph to Conway, ceases at the

Cheshire side of the ferry, he is therefore safe, but cannot give any

account of whom the passengers were; we have only learned the name of

one gentleman, whom we are concerned to relate, was Mr. Harrison, of

Limerick.

Extract of a letter from Caernarvon, Dec. 26. Yesterday morning,

the Conway Ferry Boat, together with 15 Passengers were lost; two only

out of 17 were saved, a servant and one of the rowers. I understand all

the regular rowers were not on board; some were collecting their

Christmas boxes, which probably caused the accident, as the morning,

though tempeduous and rainy, (as indeed every day has been for these

sixty days) was not very remarkably so. A foreign gentleman's body has

been driven on shore; it said he had one thousand guineas in bank notes

in his pockets. Young Rous, of the Harp-inn, at Conway, is among the

drowned. It is strange Government would not send the Mail by the

Capelcarrig[sic, Capel Curig] road, which would save the ferry, and is

twenty-two miles shorter.

Dublin Evening Post - Saturday 03 January 1807

Further

Particulars of the loss the Mail Boat at Conway Ferry. In our last we

gave a detail of the melancholy accident, by which 12 persons out of 14

passengers who were crossing this dangerous ferry in the mail boat on

the morning of Christmas day last, lost their lives; one of whom, we

have since learned, and are sorry to state, was Mr. Hunt, nephew to

Captain Fisher of the Royal Navy, who lives in Mount-str. in this city

[Cork].

The bodies of almost all the drowned persons were found and brought

on shore in little more than an hour after the accident happened. The

guard, belonging to the mail, had on his person property in debentures,

amounting to four thousand pounds, belonging to Mr. Thorpe Frank of

this city, which had been committed to his care, by Mr. Jewster the

hatter of Dame-street, to be forwarded, at the time the latter so

prudently declined crossing the ferry - the property was found with the

body, and has since been restored to the owner.

By one of the two survivors, it is stated that the man who had the

management of the boat, upon seeing the danger, cried out at the moment

to entreat the passengers to sit steadily, and threw out the anchor; but

their disobedience, and imprudent unskillful exertions to save

themselves, was the principal means of producing the fatal catastrophe.

The solicitations of Mr. Jewster prevailed upon Mr. Tilliard of

Bride-street to remain with him on shore, by which acquiescence the life

of that gentleman is also preserved.

A postchaise with three gentlemen arrived at Conway ferry, shortly

after the accident was known, but who declined crossing the ferry, and

posted back to St. Asaph, and there took the route through Denbigh, and

so on to Bangor.

Among the sufferers were Mr. Godwin, Mr.Hunt and Mr. Elliston, of

Liverpool.

It is mentioned as a fact recorded, that on the morning of Christmas

day, A. D. 1605, a boat with passengers on their way to Ireland was

lost crossing Conway ferry.