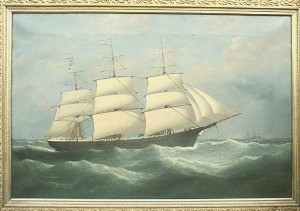

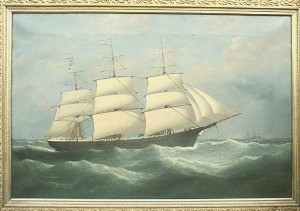

Pomona in service.

Pomona grounded on Blackwater Bank off the Irish coast and subsequently foundered

on 28 April 1859.

Position 52°26.60 N, 8°14.46 W.

American registered; 1181 tons; 3 masts; sail.

Built George and Thomas Boole, Boston 1856; owned Howland and Frothingham, New York.

Captain: Merrihew; 44 crew (20 saved)

404 passengers (3 saved)

The Blackwater Bank is about about 5m offshore of Ballyconnigar and 12m north of Tuskar Rock at the SE corner of Ireland. Ballyconnigar is the beach area near the village of Blackwater.

THE WRECK OF THE POMONA

From the Morning Post.

A new ship of 1500 tons, with a freight of more than 400 passengers, going down within sight of land but two days after it had left port, a heavy sea precluding all aid from the shore, the wreck nevertheless being so gradual as to leave the mass of human beings which had sailed in her to some 24 hours contemplation of an inevitable fate, the loss of life so complete that but 23 remained out of more than 400 to tell the tale of misery and death - these are incidents which happily do not often cluster themselves round the fate of individual men.

The Pomona, a clipper ship, 1500 tons, belonging to New York, sailed from Liverpool for America on the 27th of April with 36 sailors and 330 emigrants. For some time all was gaiety and hilarity on board. The crew had provided themselves with a piper and a fiddle, and, with their aid, dancing was the evening amusement of the passengers. Towards night as the Pomona was making her way down the Irish Channel, the breeze freshened; it blew at length a gale of wind, and the emigrants with a few exceptions, found their way to their berths. In the midst of all, this the captain lost his reckoning. The ship went aground on a sandbank, about seven miles off Ballyconigar, on the Irish coast.

Then came the terrible revulsion from alternate hilarity and repose. The few who had not left the saloons, and the many who had retired for the night to their berths, were in an instant upon deck. Some half-dressed, some with scarcely anything to cover them, were mingled together in the dark, stormy night, the clouds overhead mantling ominously black, the vessel stranded on her side, whether near or far from land, Heaven then only knew, the surge gathering in force as wave by wave advanced, "making a clear broach over her, and sweeping her decks." The terror begot confusion, shrieks uttered by helpless women, despair gravely felt by almost equally helpless men. It was a grim alternative. They might be near enough to shore to attract notice, or they might not; but whether living beings on the land heard their guns, and saw their blue rockets, or whether they did not, the sea ran too high for ship or life-boat to put out from shore. They might man their own boats or no, but no boat, it seemed could live through the storm.

But it was the business of living or dying, and for dear life's sake, discipline once more revived. The captain got his orders obeyed. The pumps were first manned, but the water in the ship's hull gained fast on all their exertions. There was, however, yet a hope. If the ship could be kept afloat during the night, the gale might moderate, and the boats might then take off the crew and emigrants for the nearest shore. The first contingency was realised; indeed the sankbank seems to have precluded the vessel from sinking, while she lay wedged, as it were, into it.

But when morning came, the gale became a hurricane. That long longing for day through dreary hours of midnight peril on the ocean, brought with it not a ray of hope. It seems that some interval elapsed between daybreak and the adoption of the desperate hazard of trusting all to the life-boats in that foaming surf. The attempt was at length made, but the life-boats were stove in and their crews were drowned. After this experiment, what more was to be attempted? Escape by means of boats was inevitable death - no help came from shore; not a stray sail appeared on that often crowded sea. A dreary night gave place to a drearier day. Hour after hour went by in baseless hope, yielding to impotent despair. But the ship remained on the bank, and they might perhaps have been thankful for that. At length it grew towards evening, and there seemed every chance that all the human beings that remained would endure another night like the past one. This seemed bad enough; but how far did that expectation fall short of the reality!

Suddenly the ship, "which had till then remained firm on the bank, slipped off by the stem into deep water, and commenced rapidly to fill." We read that "the whale-boat was then launched, and a number of the crew rushed into her." The captain, it seems, had yet a hope that the vessel would once more be driven on the bank; he accordingly let go his best bower anchor, and kept 40 men still working at the pumps. The whale-boat meanwhile pushed off with all it would contain; several were washed out of her; and, as we have said, only 23 reached the shore. The ship itself, however, rapidly settled down; and it is probable that more than 300 remained on the deck contemplating the futility of all their efforts, and reckoning what remained to them of life by the progress the vessel made in its gradual submerging. Beyond this all is conjecture; the whale-boat had pushed off, and brought no record of the last moment, when "rose from sea to sky the wild farewell."

Next day, and the day after, came the sad scene of the bodies of those who had been drowned, rolled one by one upon the shore. Much is told of the barbarity of men and women on the coast, some of whom refused to rescue the remains, while others stripped them and made off with their clothes. No doubt these instances were very exceptional, and the coastguard and others appear to have done their best in consigning the bodies to a decent grave. Whether the captain were intoxicated, or incompetent, or how he lost his reckoning in St. George's Channel, does not appear; he too was drowned, and the third mate is the chief officer among the survivors; nor does his evidence offer any explanation of the disaster. There is no doubt that of late years our own emigrant ships have been respectively commanded, and we hope that this tragedy will lead the Government of the United States to take equal precautions with our own.

Pomona in service.

Rescue attempt

On the shipwreck

becoming known at Wexford (from the sailors who made it to shore); the steam

tug Erin proceeded to the Fort of Rosslare but

the sea was so bad, and night setting in with a dense atmosphere, it was

useless to proceed. Early the next morning, with the new

Life-Boat in tow, she proceeded to the north end of the Blackwater bank, and

found the unfortunate ship sunk in nine fathoms of water, Blackwater Head

bearing W by N and Cahore point NE by N, about one and a half miles inside the

bank. Her mizzen mast head appeared over the water, with the American ensign,

union down, still flying - but the life struggle was over.

Bodies were washed ashore along the coast from Courtown to Youghal and were buried after attempts at identification and an inquest. As far as is known, no grave of the victims was marked. This is despite at least two of the bodies being identified by family members who had travelled to the scene. Many of the victims were from the Sligo area and the wreck may be the "Pomone" mentioned in a ballad about emigration from near Lissadell. More were from Northern Ireland. A full passenger list exists and some addresses were mentioned at various inquests. A memorial stone was unveiled at the bridge in the centre of Blackwater village on Sunday May 31 2009 to mark the 150th anniversary of the tragedy. The loss of life on the Pomona was the sixth worst in Irish waters surpassed by the Lusitania, Leinster, Norge, Tayleur and Rival.

Pomona memorial in Blackwater.

SURVIVORS

PASSENGERS,

Matthew LEES,

Bartholomew REILLY,

John RABER

CREW

Stephen KELLY 3rd Mate,

Richard LONG Boatswain,

Michael MORIARTY,

John SMITH,

Richard EMMENT,

Thomas BARNES,

Thomas JORDAN,

John SULLIVAN,

Harry MILLAR,

Rudolph TOMM,

Jeremiah WILLIAMS,

George MERVILLE,

George NOTT,

John RODGERS,

Charles JACKSON,

Charles THOMPSON,

James WEST,

William MURPHY,

John McCORMACK,

John MEEHAM(Passengers' cook)

Salvage

Yet, for all the grim details that were revealed at the inquests, worse was to

come when a team of divers, employed by the underwriters to salvage the

Pomona's cargo, arrived from Liverpool, later in May, and went down to

the wreck. They discovered the lifeless bodies of numbers of passengers

trapped in the hull. Among the first corpses which they sent to the surface

were those of three young females, one of whom had six shillings in her pocket

along with a passage ticket in the name of Mary O'Brien from Co. Cork.

The divers callously allowed the three bodies to float away as they got on with their grisly task - a procedure condemned as "barbarous" and cruel in the local Wexford Independent of 14th May. After that the police were notified. They obtained a boat and a supply of coffins and stood by at the wreck while the divers worked.

Report of inquiry into loss of THE AMERICAN SHIP Pomona of New York.

The following is a copy of the report to the Lords Commissioners of Privy Council for Trade of the magistrates who held the inquiry at Wexford into the wreck of the Pomona emigrant ship on the Blackwater Bank.

We, the undersigned justices of the peace for the county of Wexford, having been requested by an officer appointed by your lordships to inquire in pursuance of the Merchant Shipping Act 1854 into the circumstances connected with the wreck of the emigrant ship Pomona on Blackwater Bank on the 28th of April last, to report that we proceeded to make such inquiry on the 7th and 9th May and, after hearing the evidence which we herewith transmit and, availing ourselves of the co-operation of Capt Harris Nautical Assessor to your lordships board, submit the following as our report:

The Pomona, an American ship of 1,202 tons register, sailed from Liverpool on the 27th of April last for New York. She had on board a cargo of general merchandise, 400 emigrants, a crew of 44 men and four other persons supposed to have been smuggled on board making a grand total of 448 and of those only 24 were saved. All the regulations of the 18th and 19th Vic., called the Passengers Act, had been complied with. We therefore infer that the ship was properly found and in all respects seaworthy. The ship sailed on the morning of the 27th April with a fair wind and, between four and five o'clock that afternoon, passed Holyhead at a distance of about ten miles. From thence, the course steered was WSW till a quarter to eleven pm, when a light was observed about one point on the starboard bow. Shortly after this, the ship was hauled to the northward and eastward or away from the light and was so continued till halfpast four am when the helm was put up, the yards squared, the course steered West and in a few minutes the ship struck. Such is the brief account of the disaster which led to the loss of the Pomona. As often happens when these calamities occur, few survive to record the particulars and those few, as in this case, for the most part illiterate seamen devoid of all responsibility and ignorant of the lights or position of the ship. We can therefore only form our conclusions from the evidence brought before us.

The first position then in which we find the ship, as deposed to by the third mate, and that without any great certainty, was between four and five pm on the 27th April, then abreast of Holyhead at a distance of about ten miles. The mate states that he thinks the course steered from that position was WSW, the wind being on the port quarter and the rate of sailing might vary from six to seven knots. The course from the position assigned ten miles off Holyhead to the floating light on the Blackwater water Bank is WSW, and the distance is about sixty or sixty five miles. At eleven pm, a light was seen about one point on the starboard bow; it was thought to be revolving and was supposed to be Tuscar. Some misgiving as to its being the latter seems to have crossed the captain's mind, for after this light was seen, the ship was hauled to the northward, apparently to wait for daylight. At halfpast four am, it being then good daylight but thick showery weather, the ship was kept away due West and shortly afterwards took the ground. From evidence, it appears that the master was on deck during the first watch, for he gave the orders to haul the ship off on the starboard tack shortly before midnight. Again, he was on deck at half past four am, when he himself gave the order to the helmsman to put the helm up and steer her West. But he does not appear to have been on deck during the middle watch, when the ship was drifting to the northward with the helm a lee. That morning neither at daylight nor at any time during the previous day had the lead been hove, to verify the ship's position and, after the ship beat over the bank, the anchor was most injudiciously let go. Had this not been done it is more than probable the ship would have drifted on shore, a distance of about two miles, and many lives would have been saved.

The exertions of the Collector of the Customs and the Coastguard to render assistance were most meritorious, as also that of the lifeboat authorities at Cahore. It is to be regretted that on this occasion the shoalness of Wexford Bay and the state of the tides precluded any assistance being afforded by the large steam vessels lying in the harbour when this disastrous shipwreck occurred.

Having maturely weighed all the circumstances which appear to us to have led to this lamentable shipwreck, we are of opinion that great blame is attached to the late master Charles Merrihew inasmuch as that when the light was seen at eleven pm and supposed to have been the Tuskar, no soundings were taken to verify his position and subsequently after standing to the northward for four hours he bore up due West before any indication was given either by a light of the Blackwater Lightvessel, or a cast of the lead, of his then position. We therefore find that the Pomona was lost by default of the master. Rumours have been circulated that drunkenness and disorder prevailed on board the ship prior to her loss. We desire to remark that the evidence adduced before us disproves the truth of such allegations.

Charles Arthur WALKER JP and VL; John WALKER JP and Mayor.

I concur in the above report, Henry HARRIS Nautical Assessor

Current status of wreckage, 26/06/2014,

It is confirmed that the wreck of the American SV Pomona has been located off

Wexford. She lies in the position as reported at the time of her loss in 1859.

Extensive wreckage has been filmed by a team of divers from Dublin and the

find has been reported to the authorities. It is hoped to complete an

elementary survey in order to understand the wreck site and present findings.

It is also hoped, that the local museum in Enniscorthy, where some artefacts

from the ship are on display, may be interested in the find.

Further details:

Maritime History of County Wexford by John Power.

Into the Yawning Abyss, chapter in Between the Tides: Shipwrecks of the Irish Coast by Roy Stokes.