The lost children of the Empire and the attempted Aboriginal genocide

Published on

David Pilgrim is Professor of Health and Social Policy in the University's Department of Sociology, Social Policy and Criminology.

The Independent Inquiry into Child Sexual Abuse has concluded that British children who suffered abuse when they were forcibly sent abroad should now be paid compensation from the government. The inquiry has looked into the cases of children who were sent to Australia and parts of the British Empire from 1945 to 1970 by charities and the Catholic church. Its findings are damning.

But if society is looking for a fuller social and historical account of child abuse linked to the actions of the British Empire it will not be found in this sort of inquiry as it skirts around the fact that the parallel abuse of Aboriginal children was part of a larger eugenic effort to eliminate their race entirely.

For decades either side of the World War II, the British government supported a policy of transporting children from poor backgrounds to colonies or former colonies dominated by white settlement: Australia, Canada and Southern Rhodesia.

This transportation of poor children to key imperial outposts began in the 17th century, when the US state of Virginia was the destination. However, the most extensive activity of enforced child export – with the blessing of the British state – was between 1920 and 1970.

The findings of the report, based on unequivocal evidence, draw four main conclusions. The British government failed to ensure that the transported children were protected from harm. When reports of abuse emerged no response was forthcoming. A sensitivity about upsetting the receiving governments in large part drove that inaction. And, finally, the British government did not want to jeopardise its relationship with the voluntary sector and religious bodies, which had facilitated transport and had run the receiving institutions abroad. With a weak welfare state in the early 20th century, the British state relied heavily upon the role of those bodies.

Abuse in a loveless world

The story of these “lost children of Empire” did not emerge until the 1980s – but then more and more accounts were offered by survivors of abuse in a loveless world. The children were used as slave labour on farms. They were told that their parents did not want them or were dead. Parents trying to retrieve them were blocked in their efforts or fobbed off with empty promises of later reconciliations.

Many children were denied benign parental care – but there were those who fared much worse. They were subjected to physical and sexual abuse, often affecting their long-term mental health. Reports of the abuse were ignored by the charities ostensibly “caring” for these children. Because of their low social class and sometimes wayward behaviour, they were treated like scum or “moral dirt”.

When eventually the British Parliamentary Health Select Committee in 1998 began to make serious inquiries into the investigatory negligence of the charities implicated, they denied that any abuse was known to them. This was simply untrue, as their own excavated records showed.

Political responsibility

In 2009, on behalf of the Australian government, the then prime minster Kevin Rudd issued an apology for the harm created by the UK policy of sending children to isolated facilities abroad. In 2010, Gordon Brown also issued his apology for what he described as a “disgraceful episode in Britain’s history” and “an ugly stain that would never be repeated”.

These apologies have now been followed up by this report from the IICSA with its recommendation that the ageing survivors should now be offered compensation. We will see if that happens. With all of the named abusers in the report now deceased, there are no legal prosecutions pending.

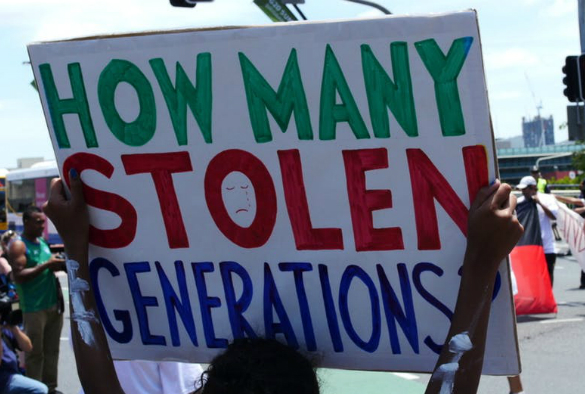

Aboriginal cultural genocide

This report is robust in its recommendations and credible in its investigatory method. However, it shares a weakness of any historical inquiry, which focuses primarily on the legal and social administrative aspects of wrongdoing. This leaves important political silences. For example, British colonialism with its eugenic character did not only export white “stock” to extend the racial reach of Empire, it also stole aboriginal children and placed them in white Christian families in a process of cultural genocide.

These stolen children were denied their birth names (which were permitted for the British children). The intention was to assimilate Aboriginal children and thereby eventually erase the existence of their race and culture.

A fuller social and historical account of child abuse linked to the actions of the British government is needed. One that contrasts the cases of the “forgotten children” who were white and the “stolen children” who were black. Both groups were neglected and abused by so called “civilised” adults on behalf of the British Empire and then by successive Australian governments until the 1970s.

But the fact is the post-colonial reckoning for these crimes is being played out unevenly, in terms of political responsibility. For example, with resonances of the attitude of the BBC about “drawing a line” under the case of abuse by Jimmy Savile on their premises, a former prime minister of Australia, John Howard, considers that the Australian state has no reason to apologise for its past treatment of Aboriginal children.

What happened to British and Aboriginal children was appalling. Both scandals need full and frank exposure and discussion. The extensive political challenge of ensuring justice for the indigenous people of ex-British colonies can be ignored but it will still remain.![]()

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.