Architecture academics on the view from your lockdown window

Deputy Head of the University of Liverpool's School of Architecture, Dr Torsten Schmiedeknecht and Martin Winchester, the School's Experimental Officer in Design Computing, asked colleagues to send in the view from their lockdown window. Here they share their favourites, alongside insights into the submissions received.

Responses from Torsten are marked with a T, and those from Martin begin with an M.

What prompted you to ask for these images?

T: After a few weeks in lockdown, seeing the same view more often than usual, I was beginning to wonder what colleagues from the School of the Arts were seeing when they settled at their desks at home. There have been surveys on work spaces I believe, and I loved the Signs of the Times BBC TV programme and book by Nicolas Barker and Martin Parr from the early 1990s. However, I haven’t seen much interest in what one sees when looking out of the window of a work space at home, which has now become the main work space for us all, and where we spend the majority of our time during the day.

What pre-conceptions did you have?

T: I didn’t really think too much about it as I knew that colleagues lived in all sorts of different environments, from urban, via suburban to rural.

[caption id="attachment_92989" align="aligncenter" width="585"] T: Only in Liverpool[/caption]

T: Only in Liverpool[/caption]

Was there more or less variety to the views than you expected?

T: I think we received a great variety of images. Not only regarding the actual space / environment, but also regarding the way people chose to take their photographs, which also says something about how different things are important to different people. Some have chosen to include and show part of the space they are working in, whereas others concentrated on the view and showed what they are seeing outside the window. This is a bit like some of the 20th century painters like Ivon Hitchens, Ben Nicholson, Winifred Nicholson and Patrick Heron who often painted views out of a window, also showing parts of an interior.

What do you find most interesting about the views?

M: How people have decided to share their spaces, from calm, contemplative space free from ornamentation, to busy family spaces transformed into impromptu offices that lose none of the artefacts that make them homes.

T: The variety, as there are so many different views and interpretations of space on display. Another thing which I think is interesting, is that most of the images, despite the variety, show some degree of normality or ordinariness. For architects and designers there is always the temptation to reinvent the wheel or to propose something spectacular, ignoring how important ordinary little things in life – and design – are. The images in the collage demonstrate that really well I think.

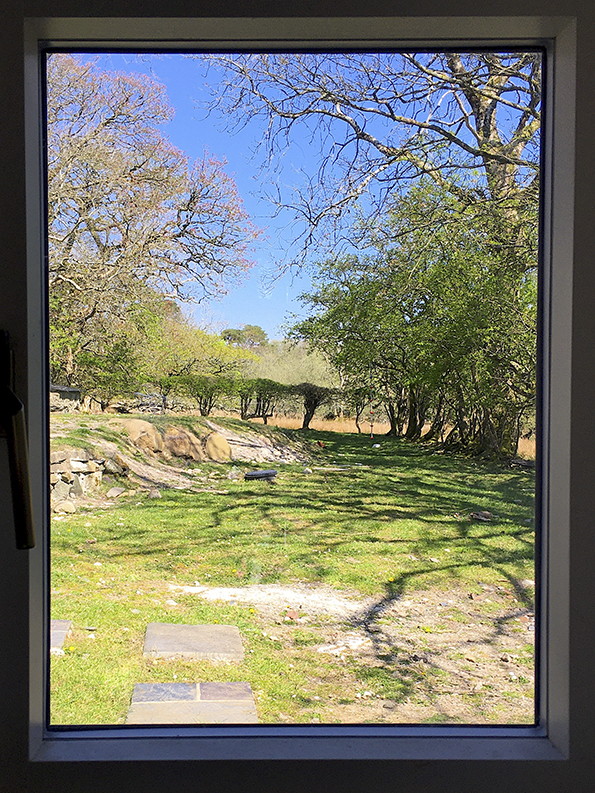

[caption id="attachment_92992" align="aligncenter" width="595"] T: Rural![/caption]

T: Rural![/caption]

What do you think they say about British architecture and landscape?

T: A lot of the images on display show buildings that are at least 50 years old, particularly in the suburban and rural environments. There are a few images taken from what looks like the upper floors of apartment buildings in Liverpool, where you can see the amazing variety of Liverpool’s architectural make-up. The majority of the images we received, however, depict either suburbia or some more rural settings. We can’t deduce anything really meaningful from this, as the sample is arbitrary and therefore not representative, but it suggests nonetheless that city centres might still have a long way to go to become more desirable locations, particularly for people living with and bringing up children. One of the problems is of course that developers prefer to build student flats or small apartments in city centres, because they are more profitable in a shorter period of time. City centre infrastructures are often not really being geared up for families.

This is the big difference between the UK and continental Europe, where more people are enabled to live in or close to city centres, because of the different make-up of the property market. UK cities have relatively small high-density centres, and large suburbs, whereas on the continent the density, i.e. apartment buildings of say 5-7 storeys, extend beyond the centre. During the lockdown, however, I imagine that living and working in a suburban house with a small garden might have been more desirable than living in an apartment with no external space, beyond perhaps a balcony. But that might just be my perception of course.

There’s probably a research project somewhere as to the suitability of different types of dwellings to more or less extreme circumstances.

My research project on the representation of modern architecture in postwar UK picture books (‘Absent Architectures: post-war housing in British children’s picture books (1960–present)’ showed that modern architecture has, with a few earlier exceptions, only recently become more acceptable as a setting for stories aimed at young children. To some degree the images we collected confirmed that good quality modern architecture as a domestic setting is not as popular (or perhaps available), as perhaps buildings originating from earlier periods. I am now (together with Jill Rudd and Emma Hayward) editing a book on the same topic with contributions from other countries and it will be interesting to see what the respective findings might reveal (Building Children’s Worlds – the representation of modern architecture and modernity in picture books).

[caption id="attachment_92993" align="aligncenter" width="585"] T: The great British terrace[/caption]

T: The great British terrace[/caption]

How particular do you think the views are to this region of the UK?

M: Although the majority of the images are taken within a 20 mile radius of Liverpool, I think you might find something similar for many of the cities of Britain. However it needs to be remembered that the images have been drawn from quite a narrow demographic and as such can only provide an insight into a subset of the population.

T: Well, we don’t really know where most of the images were taken, so it’s hard to tell, as some colleagues are in lockdown in different locations in the UK. One thing, however, from the images that we can recognise, is that Liverpool has a very unique and beautiful skyline.

[caption id="attachment_92994" align="aligncenter" width="585"] T: The (re)densification of a city centre[/caption]

T: The (re)densification of a city centre[/caption]

Do you think the current circumstances have caused people to take more notice of their immediate built environment?

T: I would think so. It probably also forced people into being more creative and inventive with regards to how to best use their dwellings in order to maintain some sort of balance between work and free time (and thus sanity!). As people are confined to either their house / flat or their local neighbourhood, I think they are also observing their immediate surroundings with more attention. I can imagine that some people are more happy with their arrangements than before the lockdown, i.e. really appreciating and enjoying their homes, whereas for others perhaps it made them think that it might be time to move on.

[caption id="attachment_92995" align="aligncenter" width="585"] M: I love the narrative of this image, there is something particularly resonant about the cat staring through the closed window at the outside world![/caption]

M: I love the narrative of this image, there is something particularly resonant about the cat staring through the closed window at the outside world![/caption]

What would be your ideal view?

T: I do (did, for the time being) like my view from my university office on to Abercromby Square. I’ve been in the same office for 20 years now – the longest time in my life that I had the same view. I love it. The view I have from my work space at home is very different, but also great. We live in a terraced house and when my wife’s studio was closed down she moved into my study to paint, so I organised a corner of the living room to be my work space. I can look onto the street, but also have a window looking out into the garden. I have really come to appreciate the double aspect and the way the light changes over the course of the day. There’s a bit of everything: buildings, trees, birds, cars, sky, and people, dogs and cats walking by.

My view has worked very well during lockdown and I consider myself to be very lucky. Our street has also really pulled together helping each other, as we have a lot of 75+ neighbours and people have organised collective shopping for this group etc. That said, I used to live in Gambier Terrace in Liverpool for a few years, and the view was absolutely spectacular. I remember particularly in the winter when, because of the fog and mist, the Anglican Cathedral was invisible in the morning and would then suddenly appear at some point during the day. That was probably the most unique view I’ve ever had from a home.

When I lived in Munich we had a great view from the third floor onto a small urban square. That wasn’t spectacular but very pretty and the square was always busy. I’ve also once lived in a remote village in Cumbria, looking on to a windmill and sheep. I am not sure though what my ‘ideal’ view would be – too many to choose from I think. Predictably and depending on my mood it could be any of the above, or a lake and a mountain, or a view from the 50th floor of a building in some mega-metropolis or other.

M: A view with trees, fields and birdsong, something I’m lucky enough to be able to enjoy!

For all the latest news and insight from the University of Liverpool, follow @livuninews

[callout title=More from Architecture]Coronavirus: why China’s strategy to contain the virus might work[/callout]