My views on gender imbalance in physics

By Olivia Voyce, 3rd Year PhD Student in Nuclear Physics

Since being one of only 3 girls in my A-Level physics class, I have been advocating for other women to study this fascinating subject. I started studying Physics at University in 2013 and have attended countless lectures, seminars and workshops focussing on tackling the gender imbalance in Physics. Yet somehow, despite all these well-meaning programmes that are delivered consistently at Universities across the UK, the gender imbalance still exists. In fact, a study performed by researchers at the University of Melbourne in 2018 found that it will take at least 258 years until there are equal numbers of senior female and male researchers in physics [1].

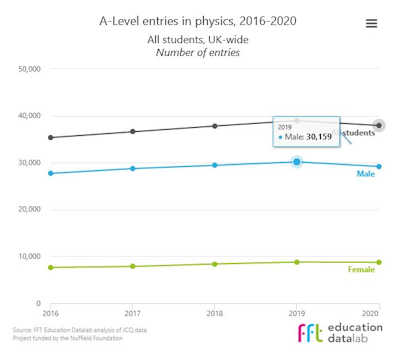

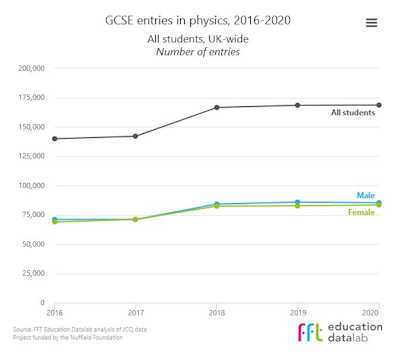

Why is this happening? And, why despite the increase in diversity quotas and female role models in STEM, is the gender imbalance in Physics still so high? I will discuss a few of the core issues here. Firstly, the uptake of physics at A-level by women is very low. In 2020, 49.4% of students taking GCSE Physics were female (when studying science is compulsory), but this dropped to 23% at A-Level (this is a consistent trend as can be seen in Figures 1 and 2 below). It is especially interesting when comparing to the Chemistry uptake. In 2020, 49.7% of students taking GCSE Chemistry were female and this actually increased to 54.3% at A-Level [2]. Why is this? It’s certainly not because women are incapable of performing well in Physics (in 2019, 90.8% of all girls taking Physics at GCSE Achieved a Grade 9-4, compared to 91.1% of boys [3]). I believe that it has a lot to do with confidence. Physics is unique in the public perception that you have to be a genius to study it. Don’t get me wrong, it is difficult, but arguably no more difficult than any other STEM subject (which have much larger female participation). However, the perception that only the top students can study the subject is daunting, and research shows us that men are more likely to be over confident in their abilities, whilst women are usually accurate in the assessment of their abilities, or underestimate themselves [4].

Figure 1. GCSE Physics entries 2016-20 (fft education datalab)

Figure 2. A Level Physics entries 2016-20 (fft education datalab)

Secondly, those female students who do progress through Physics A-Level and onto University have a whole host of obstacles to overcome, which undoubtedly affects retention. Loneliness, imposter syndrome and sexual harassment are very real challenges for female physics undergraduates. A study conducted in 2019 at the US Conference for Undergraduate Women in Physics (CUWiP) conference found that 75% of all female undergraduate physicists in the US had experienced some form of sexual harassment [5]. Seeing as the UK average for all undergraduates is at an appalling 50% [6], and sexual harassment occurs more frequently in male dominated fields, it is not a big step to infer that similar levels of sexual harassment occurs for female undergraduate physicists in the UK. This needs to be taken seriously, but is often just accepted as a hazard of the job, one that many students refuse to be a part of and therefore decline the possibility of a future academic career.

Finally, women who do make this transition into an academic career have much less support than their male counter parts. A study reported in Physics Today [7] highlights how women are much less likely to have the resources needed to advance their career in Physics. Unlike my previous points, I cannot speak on a personal level about the inequality experienced by female academic staff. However, as a final year PhD student, I am surrounded by colleagues who will not carry on in research, but are seeking jobs in industry. We have had enough and we seek something different; a place where we are treated equally, don’t fear coming to work and are valued for our input.

[1] https://journals.plos.org/plosbiology/article?id=10.1371/journal.pbio.2004956

[2] https://results.ffteducationdatalab.org.uk/

[3] https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/key-stage-4-performance-2019-revised

[4] https://doi.org/10.4102/sajip.v46i0.1704

[5] https://journals.aps.org/prper/abstract/10.1103/PhysRevPhysEducRes.15.010121

[7] https://www.aip.org/sites/default/files/statistics/international/globalsurvey2010.pdf