Filming the Footy

Posted on: 29 June 2018 by Alison Smith in 2018 posts

If you’re reading this, I guess that, for you, watching big football moments like the Euro Championship or the World Cup, is a cinematic experience. A story told on a screen. At just over an hour and a half the narrative arc of a game plays out across much the same timescale as an average feature film. And although the constraints are very different, cameras are cameras and their vocabulary is structured by their capabilities: to come in close, to sweep across space, to focus on everything in their field or to blur out all but the centre of interest. What is a football game, considered as a film?

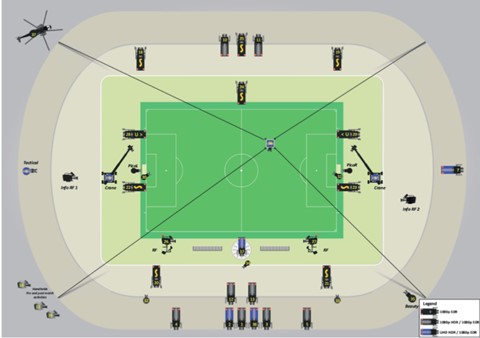

During the World Cup in 2018, each game in Russia was filmed, simultaneously, by 37 cameras. You can see their layout in this diagram:

No feature film would use so many. But a feature film director would spend weeks or even months shooting, rejecting footage, retaking, constructing. The game is edited live, in the heat of the unpredictable moment, by a team in a screen-banked command base in Moscow receiving feeds from all (or many) of those cameras, and selecting which will be shown, at any given moment, to you. Still, the strategies used are shared with feature-films. Even as the game is played, its story is constructed. Spare a thought for the complexity of the task.

Although Jean-Luc Godard once expressed the opinion that film-makers had much to learn from sports reporting, in some ways the game narrative is pretty conservative, not to say predicatable. The story must start with an establishing shot:

Long, wide, high-angle, to make sure that the audience understands that all-important geography.

Mid-shots (to give a sense of intricate action):

and even close-ups will follow, but the long shot will always come first. The editing will be on movement (not surprisingly, since games tend to move as a block in one or the other direction) and usually onto someone who was already centre screen (again, not surprisingly, since the camera follows the ball.) The basic rules of continuity are followed almost without reflection. The 180 degree rule, which film-makers often prefer imaginatively breaking, is absolute law for editors here.

Close-ups give a bit more scope for changing audience experience. After all, the point of a close-up is personal relations. When the camera focuses on their faces, players become characters, with emotions and personalities.

Close-ups change the focus and the tone: those long-shots have to be deep and clear, so that you can see what the goalie's doing at the other end of the pitch: but the close-up blurs out all but the star of the moment. Watch who gets the close-ups. Just as with feature films, they document a star system in development.

All this is very standard film-construction, with distance, long-shots and understanding at a premium over involvement. Close-ups are relatively rare, because they take time. But within the flow of the game there are fleeting moments when the editors can become film-makers, staking all on creativity, rhythm and involvement. Those moments are the flashbacks. The game has paused, they can select footage - still at lightning speed: a couple of minutes is the maximum for a flash-back montage. But footage, can be slowed down, angles can be changed (even, very occasionally, across the 180 degree line). Dramatic camera movements can be tried - the cable cam curving in over the heads of the players, for example, and down to the goal. There are a back-of-goal cameras, with their netting designs (and, here, coincidental mise en abyme).

While waiting for the VAR decision which overturned the Iranian goal against Spain at the World Cup in 2018, the camera team even experimented with split screen for emotional effect, observing the replay, and simultaneously, the players' tension and reactions in the crowd.

The footage from those 37 cameras represents a vast, unused stash of possibilities. With the benefit of hindsight, and time to reflect, could it be made to tell a different story?

Discover more

Keywords: Film Studies, Languages, Football, World Cup, Liverpool, Film, Filming, Euro Championship.