Black Lives Matter, Covid-19 and the long, cruel shadow of medical racism

Published on

Dr Stephen Kenny is a Senior Lecturer in 19th and 20th century North American History in the University of Liverpool's Department of History

The global public health crisis, precipitated by the novel coronavirus, has highlighted, more clearly than ever, deep, pervasive, historically continuous patterns of racial disparities in health, and underscored that racism itself is a major public health issue.

Alarm and just outrage provoked by the starkly high rates of Covid-19 infection and mortality suffered disproportionately by people of colour, has been productively channelled into protest and action following the unchecked epidemic of racist violence that killed George Floyd, Breanna Jackson, Ahmaud Aubery, and too many others. In this context of state sanctioned racial violence and systemic racism’s impact on Black health, the removal of racist monuments, and other racist symbols, from public space is a direct attempt to tackle the most visible symptoms of the chronic disease of racism.

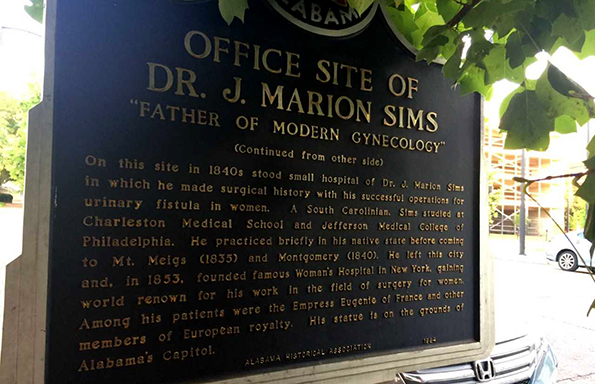

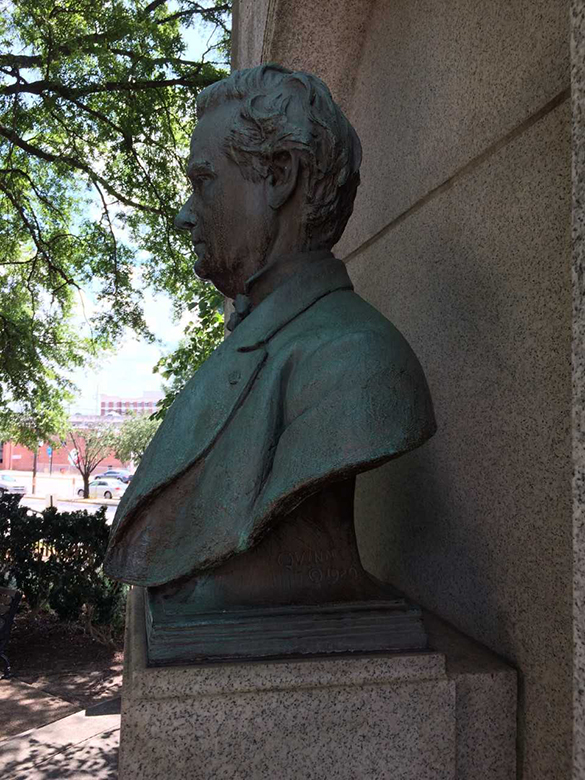

Although it is now widely known that he ran a series of gruelling and exploitative surgical experiments on enslaved women, men, and infants in a private ‘negro hospital’, located at the heart of Montgomery’s booming slave market, James Marion Sims’s dark legacy still looms in the shape of divisive, incongruous, and racially insensitive statues on the grounds of state government complexes in Montgomery, Alabama, and Columbia, South Carolina. A third Sims statue, in New York City, was removed in 2018, after an impressively determined, sustained, creative, and multi-faceted campaign by activists, artists, community groups, politicians, and scholars. But why, in 2020, given the weight of historical knowledge and the depth of public feeling, do the other two monuments remain in place and continue to disguise and glorify Sims’s career in such a partial, mythical, and simplistic manner, while causing offense, mistrust and distress?

The evidence of Sims’ medical malpractice, not to mention his racism and sexism, is not hidden, explicit in the extensive published case notes of the experimental surgeries that he performed in Montgomery, but also highlighted in his flawed and florid posthumous memoir, The Story of My Life . In this autobiography, Sims recollected that the most “memorable era” of his life was between 1844 and 1849, a time in which “there was never a time that I could not, at any day, have had a subject for operation”. In fact, these experiments were so dangerous that even his friends, family, and fellow doctors told him that he was going too far.

Sims’s enslaved patients, who were subject to repeated, coercive, and often brutal surgeries, without the benefit of anaesthesia, with little to no time to convalesce and without any meaningful choice in their ‘treatment’. The experience of being one of Sims’s surgical test subjects could only have been traumatic and the memories unbearable. Unsurprising then, that to the majority of observers now familiar with ‘his Story’, the Sims statues represent a shameful and outmoded effort to declare, institutionalize, and normalize dominion over the bodies of women, Black people, and the poor.

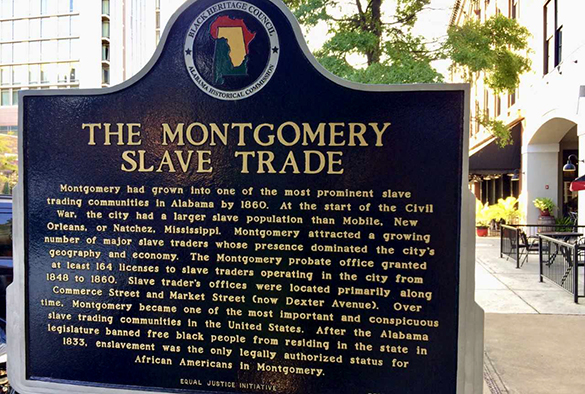

My own research shows that Sims was a typical example of a slave-owning, slave-trading, racist medical researcher, of which there were an abundance in antebellum America. Medical experiments on the enslaved were commonplace throughout the era of slavery. With a ‘negro hospital’ located on South Perry Street, just one block away from Montgomery’s main slave market and several ‘slave depots’ and ‘slave pens’, it is abundantly clear that Sims’s medical research directly serviced the slave trade. His medical writings also list major Montgomery slave-traders, such as John H. Murphy, amongst his clients.

Sims was just one of many white doctors who fed off the system of slavery’s relentless toll on Black physical and mental health, prospered not only by servicing its human traffic and cruel labor, but also by soliciting for ‘diseased and damaged’ enslaved people, bought cheaply and then sold for profit. Sims’ key role in the cruel business of human trafficking only adds to the urgent need to rethink all of his memorials.

Given the pain, sickness, and distress that such racist statues cause, it is a wonder that it has taken so long for these two most toxic of memorials to be removed. Bryan Stevenson, executive director of Montgomery’s Equal Justice Initiative, has repeatedly made clear that he believes these monuments should be removed, because by doing so society recognises that they shouldn’t ever have been there in the first place. Unburdening public spaces of monuments to white supremacy and black oppression presents exciting new opportunities to honour instead individuals and movements who have affirmed life and fought for equality and justice.

The case is clear and urgent: there should be no public place of honour for tributes to slave traders, advocates of slavery and racism, or surgeons like James Marion Sims who exploited Black bodies for profit and for personal advancement. Yet, there is at the same time room for a fruitful discussion as to how best to serve the cause of tolerance and the anti-racist education of future generations. Valuable distinctions might be made between, on the one hand, deeply offensive and unacceptable public tributes that were deliberately erected to honour and perpetuate the memory of enslavers and, on the other hand, the future role of the buildings that enslavers inhabited and the objects that they used or collected. Much can be learned from such buildings and objects, such as the site of Sims’s former office building and his speculum and related surgical instruments on display at the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture, and of course from the things that enslavers and slave-trading enslaver-physicians like Sims wrote.

The retention of traces of a country’s racist past - if radically transformed from tributes to that racism - can create rewarding journeys of exploration and pathways to new understandings.

For all the latest news and insight from the University of Liverpool, follow @livuninews

[callout title=Dr Stephen Kenny]American medical experimentation on slaves “frequent, commonplace and widespread”[/callout]