How the events of September 11 influenced US foreign policy for two decades

Published on

Dr Michael Hopkins is a Reader in American Foreign Policy in the University of Liverpool's Department of History

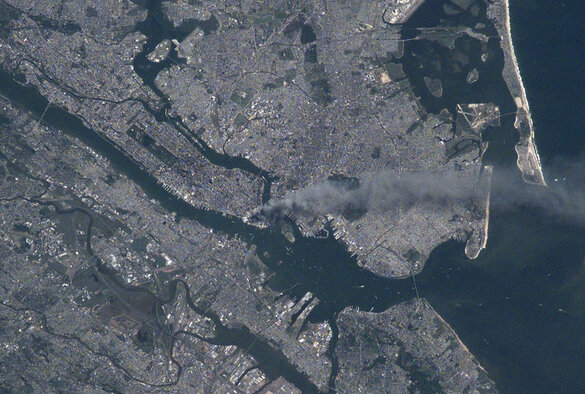

The brutal terrorist attacks on the World Trade Center in New York and the Pentagon in Washington on 11 September 2001 caused massive trauma and anxiety about further attacks, followed by a general sense of uncertainty. President George W. Bush then took bold actions. He introduced major new security procedures and created the Department of Homeland Security. The attacks also transformed US foreign policy. The United States would not only hunt down the perpetrators of these acts, it would commit itself to what it called the global war on terror. The new doctrine stressed American primacy and the use of pre-emptive war. As Bush announced in June 2002, “We must take the war to the enemy, disrupt his plans, and confront the worst threats before they emerge.”

What were the consequences of this doctrine?

Within weeks, America attacked Afghanistan, whose Taliban regime hosted Osama Bin Laden’s al Qaeda, who launched the 9/11 attacks; and secured the support of its NATO allies by invoking article 5 that regarded an attack on one country as an attack on all the alliance. US air strikes, combined with small numbers of CIA operatives and special forces on the ground working alongside anti-al Qaeda Afghans, quickly defeated the Taliban – and at the cost of only one US death in combat. But they failed to capture or kill Bin Laden. Eventually, he was located in Pakistan and killed by a special forces assault in 2011.

Needing to ensure the Taliban would not return, Bush committed ground forces and sought to build a stable Afghan government but this was done on the cheap. Meanwhile, Bush, vice president Dick Cheney and defense secretary Donald Rumsfeld had another goal in their global war on terror – Saddam Hussein’s Iraq and his alleged weapons of mass destruction. In March 2003 the Americans invaded and swiftly conquered Iraq, again utilising sophisticated weaponry to devastate the enemy, but deploying too few ground forces for effective occupation and wholly inadequate against the insurgency that emerged by late 2003.

In 2006-2008, Bush greatly increased ground troops in Iraq, which brought gains against the insurgents sufficient to lead to an agreement with the Iraqi government to withdraw US forces by December 2011. Bush also sent more troops to Afghanistan but was rather complacent about the situation there. Barack Obama took office in 2009 and implemented the December 2011 withdrawal from Iraq. He wanted also to end American involvement in Afghanistan but decided that this first required defeat of the Taliban and a stable, democratic Afghan government. Vice president Joe Biden argued against sending more troops but signed up to the new policy. US and various NATO forces were involved in vicious fighting that pushed the Taliban back but did not drive them from all regions of Afghanistan. In 2014 Obama ended US military operations, as did the other NATO allies.

Much progress had been made in the capital, Kabul, which had many features of a modern city. Above all, life had changed for women in the capital and, to varying degrees, in other parts of the country. But most of Afghanistan was deeply conservative and the government and its many agencies were rife with corruption. All this was known by American and other NATO authorities but key figures repeatedly gave upbeat briefings about the situation.

When Donald Trump became president, he adopted a nakedly America first strategy of quitting Afghanistan. He reduced US forces from 18,000 to 8,000 and signed a deal with the Taliban in February 2020 agreeing the withdrawal of all US personnel, civil and military, by May 2021. Joe Biden assumed office in January 2021 and declared 31 August as the date of withdrawal, which proceeded amid chaotic scenes at Kabul airport. Still worse was the Isis-K bomb that killed 13 Americans.

Biden had achieved something he long desired but justified his actions by misrepresenting the history of US involvement and misjudging the consequences of the departure. He claimed that the objective had been to capture or kill Bin Laden and destroy al Qaeda in Afghanistan and not to pursue nation-building. Yet, he was part of the Obama administration that greatly expanded efforts at nation-building. He was determined to end what he called a “forever war.” Yet he did not challenge the even longer and much larger commitment of American forces in South Korea since the Korean War armistice of July 1953. He claimed in July that Afghan forces were capable of resisting the Taliban without US military aid. When they rapidly collapsed in the next couple of weeks he did not acknowledge his miscalculation and, instead, blamed the Afghan leaders and military.

Have we now reached another turning point in America’s position in the world? Is the retreat from Afghanistan a harbinger of American retreat from the world? Never underestimate the United States – it overcame Vietnam to prevail in the Cold War and retains its formidable military power. But the international situation is very different in 2021. China, unlike the Soviet Union, is a significant challenger to America across a range of areas from technology to trade, from global influence to its growing military power. America’s relationship with allies is also less secure. Biden announced that America is back as an internationally engaged power and willing and eager to cooperate with allies. And then the first major decision he takes, the withdrawal from Afghanistan, was made without consulting those allies. We seem to be entering another period of uncertainty for US foreign policy.

[callout title=More]How 9/11 changed cinema[/callout]