Iron paddle steamer Brigand, built Page & Grantham, Liverpool, 1840

513 grt, 470 tons(bm), draught 7.5 ft, engines 200 hp.

Owned J. E. Redmond, Wexford. Registered Wexford.

Initially sailed from Wexford to Liverpool and to Bristol, weekly

Voyage Liverpool to London for St. Petersburg.

12 October 1842, struck Bishop Rocks, Scillies and sank in 45 fathoms.

Captain Robert M Hunt and 27 crew saved in 2 ship's boats.

From Liverpool Mail - Tuesday 19 May 1840

Launch of an Iron Steam-Vessel. A splendid iron steam-vessel,

called the Brigand, of 470 tons measurement, was launched, Saturday

last, from the new building-yard of Messrs. Grantham, Page, and Co.,

at the south end of the Brunswick Dock. This vessel, built for E.

Redmond Esq. of Wexford, and is intended to run between that port and

Liverpool. The spirited proprietor is the owner of the Town of

Wexford steamer; but, in consequence of the dangerous state of the bar

of Wexford harbour, in easterly winds, she is not able, at all times,

to carry cargo. Mr. Redmond was, therefore, induced to order a vessel

of iron, to ensure a light draft of water; and his expectations, in

this respect, are likely to be fully realised, as she will be enabled

to carry a heavy cargo on 7ft. 6in. water. The principal peculiarity

of this vessel, over any that have yet been built of iron, is that she

is to be employed in the heavy carrying trade of the Irish channel,

and has consequently, been made much stronger than any that have

preceded her; and although, probably, her hull weighs nearly 100 tons

less than if made of oak, her strength will much exceed timber-built

vessels. From the long experience of the builders, it may be expected

that every means will be employed to make the Brigand as complete as

possible, to increase the confidence in iron vessels which is

everywhere springing up. - Albion.

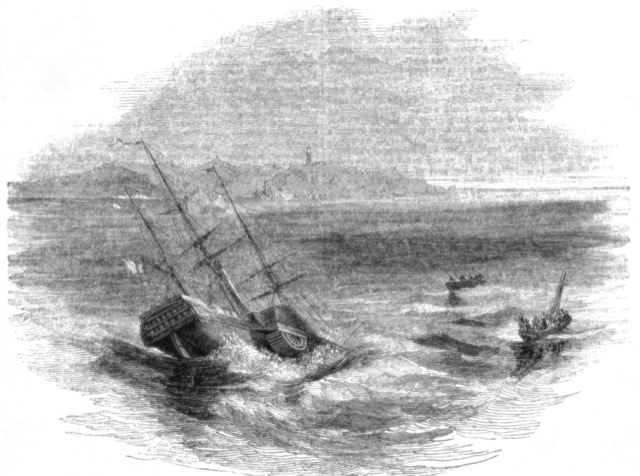

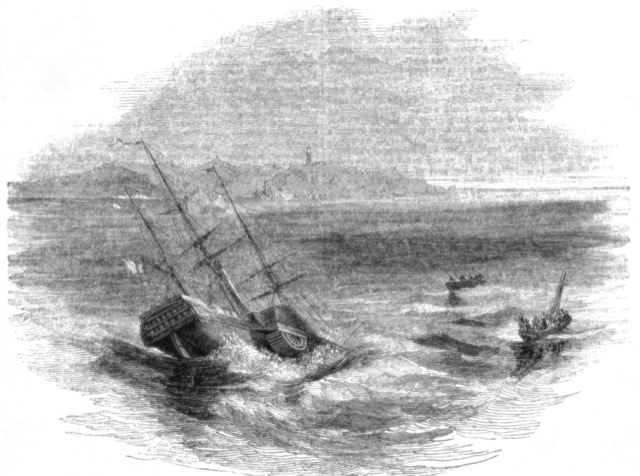

Image (from Illustrated London News) of wreck

From Bristol Mercury - Saturday 22 October 1842

WRECK OF THE BRIGAND STEAMER. Intelligence reached Bristol on

Saturday morning last, of the loss of the new iron steamer, Brigand,

on the Wednesday preceding, near the Scilly Islands. This news

created considerable excitement in the mercantile world, and more

particularly so from the fact of the Brigand having been built to

trade between Bristol and Liverpool, calling at Wexford, in which

trade she had been employed for the last two years, having left the

station only a fortnight since for the purpose of proceeding from

London to St. Petersburgh, for which port she was intended to sail

from the St. Katharine dock on Thursday last.

The Brigand was one

of the largest and most beautiful iron steamers ever yet built, being

600 tons burthen, and of 180 horse power, and was remarkable for

the beauty of her workmanship, the splendid fittings of her saloon,

and her extraordinary speed. She cost in building £32,000. The

steamer Herald, from Hayle, arrived at Bristol in the course of the

morning, bringing the crew of the unfortunate vessel.

It appears

that the Brigand, having taken in upwards of 200 tons of coals, and

a large quantity of patent fuel, for her consumption on her voyage

to St. Petersburgh, sailed from Liverpool for London at two o'clock

on Monday afternoon, and proceeded safely on her voyage until five

o'clock on Wednesday morning, when they saw the St. Agnes' light,

which, from the refraction of light, the weather being very hazy, they

conceived to be at a considerable distance - they were then steaming at

12 knots an hour. The wind was light, but there was a strong current

setting in for the Bishop rocks. Suddenly the man on the look-out at

the bow sang out "Breakers ahead!" which they distinctly saw, but

too late, unfortunately, for the rate at which they were going was

such that they could not stop her; and, although they put the helm

hard a-port, to endeavour to shave the rock, the vessel immediately

afterwards struck most violently, and two plates of the bluff of her

bow were driven in. She rebounded from the rock, but in an instant

afterwards, such I was the force of the current, she struck again,

broadside on, the force of which blow may be in some measure conceived

from the fact, that it actually drove a great portion of the

paddle-wheel through her side into the engine-room.

The vessel was

built in four compartments, the plan adopted in iron ships, or she

would have gone down instantly, two of her compartments being now

burst, and the water rushing into them at a most fearful rate. By the

two shocks four and a half plates were destroyed, and four angle irons

were gone in the engine-room. The two compartments aft being, however,

still water-tight she continued to float, and every exertion was used

by her commander, Captain Hunt, for upwards of two hours, to save her,

when the crew took to the boats, and shortly afterwards she went down,

about seven miles from the rock, in forty-five fathoms of water. The

mate attributes the loss to the strong current setting then upon the

rock, and to the haze having deceived them as to the distance of the

St. Agnes' light.

The men belonging to the engineering department give

the following interesting narrative of the occurrence. They say that,

having left Liverpool on the Monday afternoon, every thing proceeded

well until a few minutes before five o'clock on Wednesday morning, the

vessel then going at full speed, her engines making upwards of 20

revolutions in the minute, being then, as they have since learned,

close off St. Agnes. They were at work below in the engine-room, when

suddenly they felt a tremendous shock, accompanied by a report like

the roar of cannon, and almost instantaneously a second shock, and

the water rushed in in a fearful manner. They immediately ran on deck,

and found that the vessel had struck the rock, as before described.

One of them was then ordered by the Captain to assist the carpenter

in endeavouring to stop the leak, for which purpose he went down into

the engine-room, where they were still trying to work the engines, but

the paddle-wheel being driven in, had torn the injection-pipes, so

that they would not work, but at slow motion; the engines were kept

working, the Captain (as one man imagines) not thinking the leak so

bad, and that they could get the better of it, or that, as the weather

was so moderate, they might reach some port. On examining the leak in

the engine-room, they found a rent of at least five feet in length,

the rivets being started, and the plates broken, through which water

rushed in a truly fearful manner. They immediately procured a plank,

and having fixed it against the leak by means of stays to the

cylinder, they got a quantity of waste tow and grease, which they

stuffed in and endeavoured to keep out the water, and partially

succeeded in doing so; but the other leak in the forehold, being out

of reach, rendered all their efforts ineffectual; and the water,

continuing to pour in, soon put the fires out, after which, there

being more than four feet of water in the engine-room, they were

compelled to quit it. In the meantime, another portion of the crew had

been ordered by the Captain to go into the hold and throw the coals

and patent fuel overboard, in order to lighten her, and blue lights

were burnt and other signals of distress made. The men went to work

steadily in the hold, getting out the coals, etc., until the water

having gained very much upon them, they rushed on deck. The Captain

having, however, addressed and encouraged them, they returned to the

hold, and continued their exertions for about a quarter of an hour

longer, when the water having risen over the hatches of the lower

deck, they were compelled to quit the hold.

The Captain then called

them all aft on the quarter-deck, and finding that no further

exertions could be made to save the ship, and that she was then fast

sinking forward, the sea at that time breaking over her bow, ordered

them to make preparations for saving themselves, and the two boats

belonging to the Brigand (both jolly boats) were got out, and the crew,

27 in number, placed in them. The captain and mate remained on the

quarter-deck of the unfortunate vessel until the last. The boats,

which were completely crowded, then shoved off, and in a few minutes

the Brigand disappeared, sinking head foremost, about seven miles

from where she struck, and in deep water. The weather, fortunately,

was at this moment particularly moderate, or the boats, in their

crowded state, could not have lived in the sea, and not a soul most

probably would have been left to tell the tale. Having rowed to the

rock, upon which they landed, to survey the coast, they shaped their

course for St. Agnes' Bay, where, to their inexpressible joy, they saw

two boats, well manned, coming to their relief, by whom (the men in

the Brigand's boats being much exhausted from their exertions on

board) they were taken in tow, and about three o'clock in the

afternoon they were fortunately landed at St. Mary's, Scilly, - without

the loss of a single life. The shipwrecked crew then proceeded in a

pilot-boat to Penzance, and were kindly conveyed, passage free, to

Bristol, in the Herald.

The rocks upon which the Brigand was lost have

proved peculiarly fatal, no longer ago than 1841 the Thames steamer was

wrecked within three miles of the same spot, and went down with such

rapidity that 60 or 70 lives were sacrificed. Various suggestions have

been made by nautical men here as to the cause of this wreck, some

saying that the steamer ought not to have gone within many miles of

the Scilly Islands; and that, the weather being moderate, she was

not driven there: while, on the other hand, it is urged, that from

the haziness of the weather she was not aware that site was so near

until too late, the refraction of light deceiving them as to the

distance of the St. Agnes' light; and the current, which is very

strong there, and runs for nine hours in the one direction, and only

three hours in the other, having set them down on the rock.

Unfortunate, however, as this accident has been, it has decidedly

proved the advantage of iron vessels built in compartments; for, had

the leak affected only one compartment, she would undoubtedly have

been saved, and even although, by the extraordinary fact of her

rebounding and striking a second time, two compartments were burst,

yet she floated for more than two hours and a half, enabling the crew

to save themselves: and had they had sufficient boats they could have

saved a good deal of property; while, if she had been built of wood,

she must with such injuries have gone down in less than 10 minutes,

and all hands would have perished.

From Liverpool Standard and General Commercial Advertiser - Tuesday 18 October 1842

LOSS OF THE BRIGAND, IRON STEAMER. The following letter has been

received from the captain of the Brigand, iron steamer, which was

unfortunately wrecked, off the Scilly Islands, on Wednesday last:

"I have the misfortune to acquaint you that the Brigand struck on one

of the sunken rocks to the westward of the Scilly Islands, called

the Bishop's Ridge , between four and five o'clock on

Wednesday morning last. I had made St. Agnes' Light some time before,

broad on the larboard bow, and steered S.W. by W., a course which you

will perceive, on every reasonable calculation, should have taken me

clear many miles. The wind was east at the time, and the morning hazy,

making the light appear far more distant than it really was; an

effect (as the inhabitants informed me) always the result of similar

circumstances, and which set ordinary calculation at defiance. I

myself first saw from the quarterdeck the ripple of broken water. The

helm was instantly put hard a-port, when the vessel touched on her

larboard bilge, before the paddle wheels. Two plates, at each side of

the water-tight bulk's-bead, which separate the engine-room from the

fore hold, were broken in. The engine pumps were immediately rigged,

and every endeavour made, but in vain, to staunch the leaks. In

expectation that the water-tight compartments, forward and aft, still

free, would keep the vessel afloat, all hands were set about throwing

overboard 20 tons of patent fuel, stowed between decks; but she

settled down so rapidly by the head, that it became my duty to order

them to the boats. We were 28 in number, and with 14 in each boat, we

shoved off. One boat, in charge of the first mate, I directed to be

pulled immediately to the islands, and returned in the other close to

the vessel, in order to board her again if she remained above water.

About a quarter of an hour afterwards, rising perpendicularly half her

length aft, she went down with a fearful noise, head foremost, the

water spouting through her cabin windows high into the air. You may

imagine the varied feelings that crowded on my mind as our boat,

gunwale down, with her load of 14 souls, floated on the brink of the

vortex made by our sunken ship. After six hours rowing we reached the

shore. But amongst all my cares, I have one solitary gratification to

the conduct of the crew. Not a man went near the boats until I gave

the order to do so; and from the moment the vessel struck until I

took leave of them all safe at Bristol, on Saturday morning, the same

obedience and respect was shewn me as when I walked the deck, their

commander. With the Assistance of the Society for the Benefit of

Shipwrecked Seamen, and from their own willingness to remain under my

control, I had the happiness of being able to provide for their

wants, and to forward them all to their homes -

Sincerely yours, "ROBERT M. HUNT."